How Tasmanian Indigenous rebels went on the run in Victoria

A report of the dawn arrest of a band of Indigenous rebels in November 1841 in Victoria brilliantly captures the tension and drama.

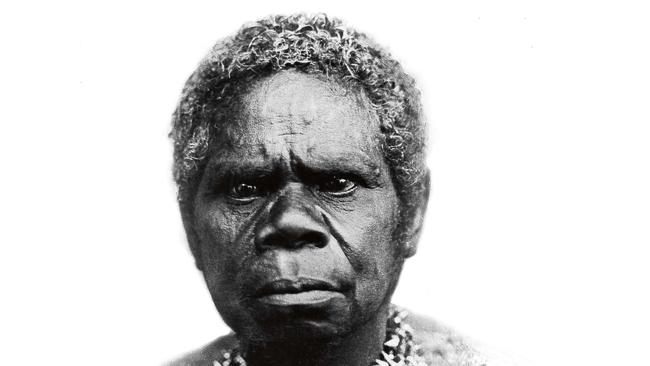

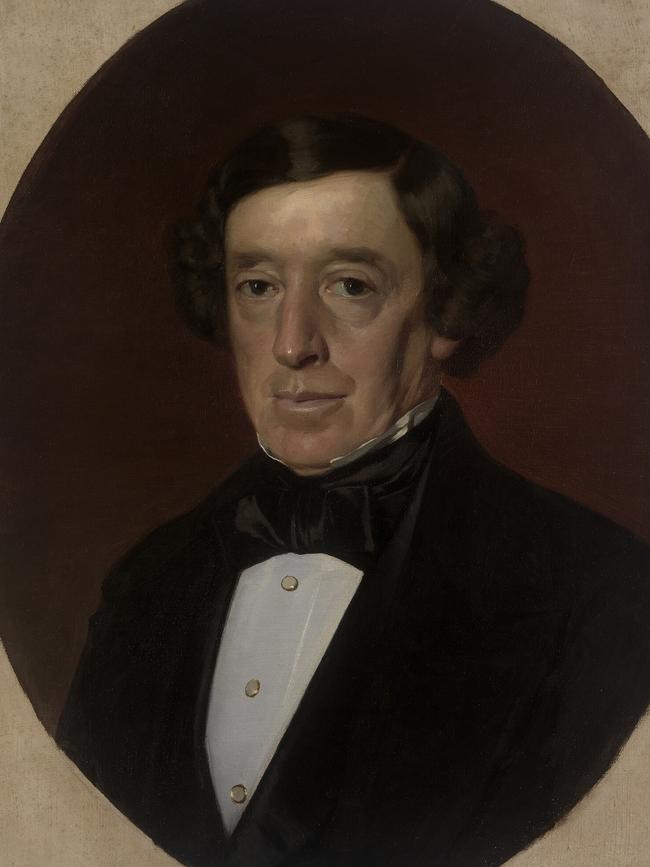

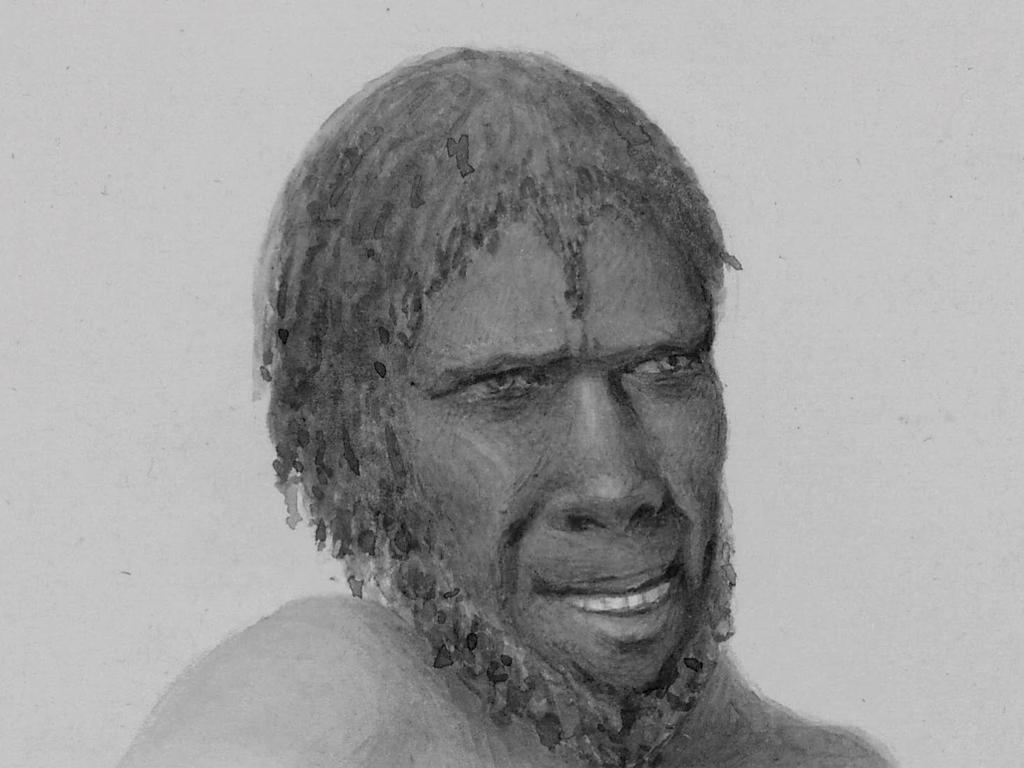

At Port Phillip in 1841, five Tasmanian Aborigines – two men (Pevay and Timme) and three women (Trukanini, Planobeena, and Mathabelianna) – who had been taken to Melbourne by George Augustus Robinson, the Chief Protector of Aborigines, rebelled against his restrictions and absconded. Although peaceful at first, they later killed two whalers after mistaking them for men falsely identified as the murderers of Mathabelianna’s husband. For the next six weeks the five rebels raided Mornington Peninsula and Western Port settlers, stealing weapons and supplies while evading a posse led by three officials: Commissioner of Crown Lands Frederick Powlett, Ensign Samuel Rawson, and Assistant Protector of Aborigines William Thomas. Late on November 19, the pursuers located the rebels’ camp and decided on a pre-dawn surprise attack.

The rebels’ fireless and famished pursuers woke before dawn next day, chilled and damp. “I don’t know that I ever felt the Cold like it,” Thomas recalled, “all our teeth chatter’d. We just got lights to our pipes, & the (blacktrackers) are off … up to our knees in mud and water.” It was November 20, 1841. Pevay and Timme had just two months of life left.

Rawson described the posse’s stealthy advance:

“(We) arose about 4.00am, a cold morning, heavy dew falling. Having examined our arms to see that all was right, we marched in silence in single file, the blacks leading to point out the way, which lay under a range of sand hills about half a mile (800m) from the sea. After advancing half a mile we had to cross a lagoon, water two feet (60cm) deep, anything but pleasant on a cold morning with an empty stomach. We advanced some time, till we began to think the guides had lost their tracks, when just as the sun was rising, they pointed out the smoke of the fire, rising above a few shrubs about twenty or thirty yards below us. We were on a sand hill, at the bottom of which was the camp and immediately beyond that was a thick scrub, almost impassable for a black man, and quite so for a white man, and as they had dogs with them, I was afraid of their giving the alarm and giving them an opportunity of hiding in the scrub.”

For their surprise attack on the rebels’ camp, said to be sited between the dunes and Lake Lister due west of today’s Rifle Range Reserve in Wonthaggi, the posse was deployed in two parts. “(W)e fell in, I and 4 Blacks & Mr Powlett and party on right, Mr Rawson & party and 3 Blks on left,” Thomas related.

Rawson described their careful approach:

“I extended the men along the top of the hill, and then myself in the centre advanced in a kind of semicircle down upon them. Each man was six feet (1.8 metres) apart, with orders to take them alive if possible, but if they offered resistance or to escape to shoot them at once.”

As they crept down the hill in the waxing light of daybreak they could see the recumbent forms of the sleeping rebels and their dogs around the campfire about 20m away. Despite their number, the posse managed to advance so quietly that their surprise was absolute. Then they all fired. Rawson claimed it happened when a policeman discharged his gun prematurely, but Thomas wrote that they “all let fire at once”. The sudden fusillade shattered the dawn stillness. Chaos followed. The rebels’ dogs scattered and fled. Timme leapt up and ran into the adjacent bushland, abandoning his weapons. Pevay and Trukanini bolted into a different part of the scrub, but she fell when hit by one of Rawson’s shots. He had “fired both barrels, right and left, and I saw one drop”, he said. His ball hit Trukanini’s head but “ploughed through the scalp without fracturing the bone”. Pevay, meantime, had disappeared, although those chasing him through the bush could hear underbrush snapping under his running feet.

Rawson acted decisively to stop the fleeing rebels:

“I immediately ordered the men to surround the scrub to prevent their escape, and then I went to reconnoitre the camp … (F)rom the heavy fire opened upon them, I concluded they must all be shot. While I was turning over the blankets with the end of my gun, I discovered a woman. I handed her over to a policeman to put handcuffs on her and a little further I discovered another.”

Like Planobeena and Mathabelianna, the stunned and bleeding Trukanini was quickly secured. Rawson then used the women to force Pevay and Timme to surrender:

“After (the women) were secured I put a pistol to their heads and told (them) to call their companions out of the scrub if they were alive … Just now a man (Timme) was taken escaping from the other side of the scrub, and directly after, we saw the other haring across the country near half a mile off …”

Unencumbered and having a good start, Pevay might have escaped. But he was their comrade and their leader. When Rawson forced the women to call out to him to surrender, he did. He stopped running and allowed himself to be seized by Corporal William Johnson and Trooper William Limont of the Border Police.

“We thus had the whole party and to our astonishment only one (was) wounded … tho’ … about thirty balls were sent at their heads,” Rawson wrote in his journal.

Thomas was more succinct: “By ¼ past 6 it was all over.”

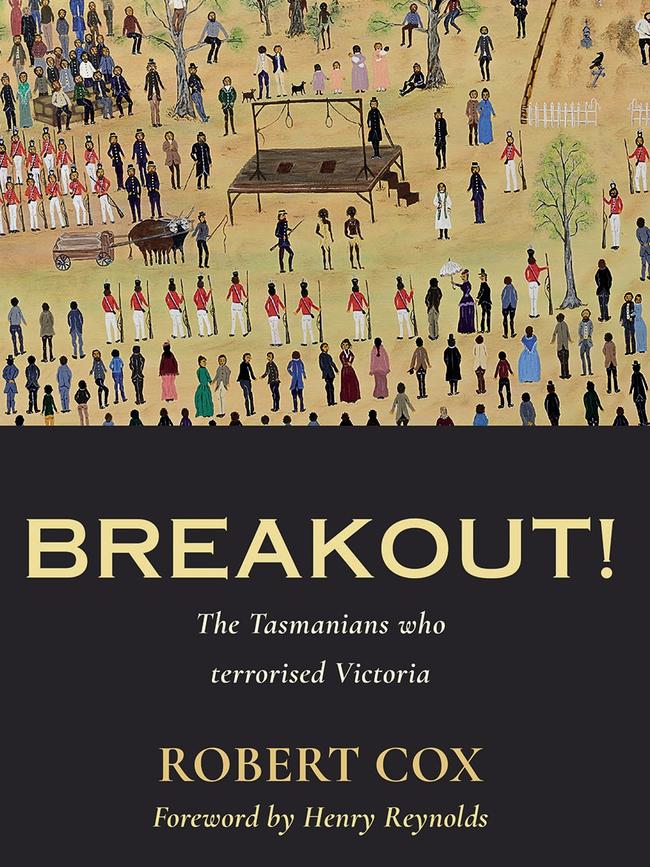

This is an edited extract from Breakout! The Tasmanians who terrorised Victoriaby Robert Cox, Wakefield Press, $39.95

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout