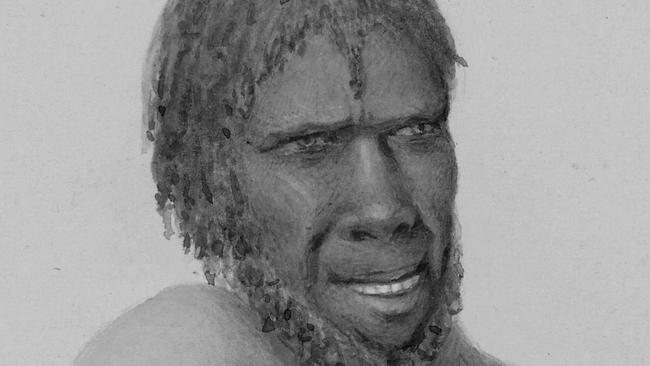

Kikatapula: leading the resistance

Indigenous warrior Kikatapula incited Australia’s bloodiest frontier war.

Kikatapula, known to whites as Black Tom Birch, was a Palawa (Tasmanian Aboriginal) man who was once the most feared and hated figure in Van Diemen’s Land. After working, in his youth, for a wealthy settler family, he subsequently joined a detribalised mob led by an exiled mainland Aboriginal man known as Musquito.

Late in 1823, Kikatapula incited the attacks that led to Tasmania’s eight-year Black War. A few months later, Kikatapula was first recorded as leader of a raid on colonists. The attack was at Pooles Marsh (now Lower Marshes) in the Lower Midlands and the victims were Matthew and Mary Osborne, who lived a short distance from the Hobart-Launceston Rd about 6km northwest of Jericho.

Late on June 9, 1824, just after Matthew had returned from several days in Hobart, an unidentified convict servant of a nearby settler called at the house and offered to sell Mary a kangaroo, which she agreed to pay for with tobacco.

Unaware that her husband was back, the convict was startled when Matthew spoke to him. “Oh, Mr Osborne,” he said, “is it you? I thought you were in camp (Hobart).” He told Osborne he had come to ask for food for two poor blacks nearby who were in need.

Mary was immediately fearful. “What could you mean by bringing them about the place?” she gasped. “Did you mean them to murder me?” The convict assured her that they were “tame”. (In the early 1800s, the word “tame” was used by Tasmania’s white settlers and convicts to refer to seminomadic indigenous bands who coexisted peacefully with them.)

The convict had been sitting peaceably at the blacks’ fire for the last two hours, he said. At that moment a Palawa man appeared whom Osborne recognised as “Black Tom, the notorious companion of Musquito’’. He was immediately apprehensive.

“You must be a very bad fellow to consort with such a murderer,’’ he said fearfully, “especially knowing how many acts of barbarity he has lately committed’’. The convict said he didn’t care. “I would not betray him for three free pardons, and £50 besides.” Thoroughly alarmed, Osborne gave a dish of potatoes to the convict, who took it to Kikatapula. Both then went away.

Next morning, as Mrs Osborne was at work in the dairy, her husband rushed in crying, “Oh Mary, Mary, the hill outside is covered with savages!” The terrified woman prepared to flee but Osborne managed to calm her, telling her not to be frightened but to go into the house while he stood guard outside. As Kikatapula led the Palawa toward him, Osborne, armed with a musket, asked what they wanted.

“Are you hungry?” “Yes, white man, yes,” Kikatapula replied. The jittery Osborne said that if the Palawa laid down their spears and lit a fire he would bring them potatoes and butter. He also called to his wife to cut up a large loaf of bread and give it to them, but she was so rattled that she could do no more than break it in two. Again Osborne asked the Palawa to lay down their spears. “We will,” Kikatapula said, “if you, white man, put down your musket.’’ After a brief parley both parties laid down their weapons.

The Palawa then came up to be given potatoes, which they ate after roasting them with their firesticks. Some Palawa then went into the house and asked for more, which Osborne went outside to fetch. But as he stepped back inside he saw that his musket had disappeared. “I’m a dead man!” he groaned. Kikatapula, following him back into the house, began pointing at various household items, saying, “I must have this, I must have that”.

Very much in command, he snatched Osborne’s hat and put it on his own head. The settler was momentarily relieved when two Palawa grasped his hands in apparent amiability, but as they did a warrior behind him plunged a spear so forcibly into his back that he screamed and bounded forward before falling dead.

Shrieking “Murder! Murder!” Mary fled, pursued by Palawa who speared her in the head and side before beating her senseless with waddies and leaving her for dead.

But she did not die. Despite her wounds and loss of blood she managed to crawl about 5km to the hut of a neighbour, John Jones. He took the badly wounded woman to Jericho, where Dr John Maule Hudspeth nursed her back to health. When Hudspeth and others went to the Osbornes’ farm they found Matthew Osborne’s corpse and a hut stripped of possessions.*

Kikatapula quickly became so notorious as the leader of Palawa resistance that a Hobart newspaper called for him to be lynched immediately on capture. But when he was apprehended in late 1827, Lieutenant Governor Arthur spared him on condition he work for the British.

For the next year he worked as a guide for a roving party led by Chief District Constable Gilbert Robertson, who was endeavouring to round up hostile Palawa, but Kikatapula constantly and effectively sabotaged Robertson’s efforts and persuaded other Palawa guides to emulate him.

Eventually their chicanery became so obvious that Jorgen Jorgensen, leader of an Oatlands-based roving party, could report that the main impediment to success was “Black Tom and the other Blacks accompanying the expedition not being willing to bring the parties to where the natives would very likely to be – I have this from general opinion chiefly”, to which Colonial Secretary Burnett added a marginal note: “I think this extremely probable.”

Historian James Bonwick recalled Jorgenson telling him, “I have not found one (Palawa guide) that I could recommend, or seem fit to be a negotiator between us and his countrymen. Eumarra, Black Tom, and Black Jack (Cowertenninner) … possess much cunning, but little manly sense, and they are otherwise corrupted.”

William Grant, leader of another party, made the same observation about Cowertenninner. After spotting a Palawa in the bush one evening, he reported, his party set out at first light next day (July 4) to track him but were stymied by their guide. A comment magistrate Thomas Anstey scrawled in the margin of Grant’s report confirmed that Cowertenninner was emulating Kikatapula.

“This conduct in Black Jack corresponded with the supposed conduct of Black Tom,’’ he wrote, “as related to me by letter by Captain Robson, a new Settler on the Upper Macquarie River.’’

Hampered by those counteractions and his own ebbing enthusiasm, Robertson recorded no captures at all in 1829. Yet during the eight months of his unsuccessful third sortie, in the very areas he and his men were fruitlessly combing, Palawa slew at least 19 Britons, wounded 38 more, and made 23 other raids on settlers. Kikatapula’s passive resistance had been notably effective.

Kikatapula spent the last 28 months of his life as guide and interpreter for George Augustus Robinson’s Friendly Mission, which he also opportunely misled. Aged about 30, he died in Robinson’s service in May 1832.

*This description of the attack on the Osbornes is based on the account of survivor Mary Osborne, published by the Hobart Town Gazette on July 16, 1824.

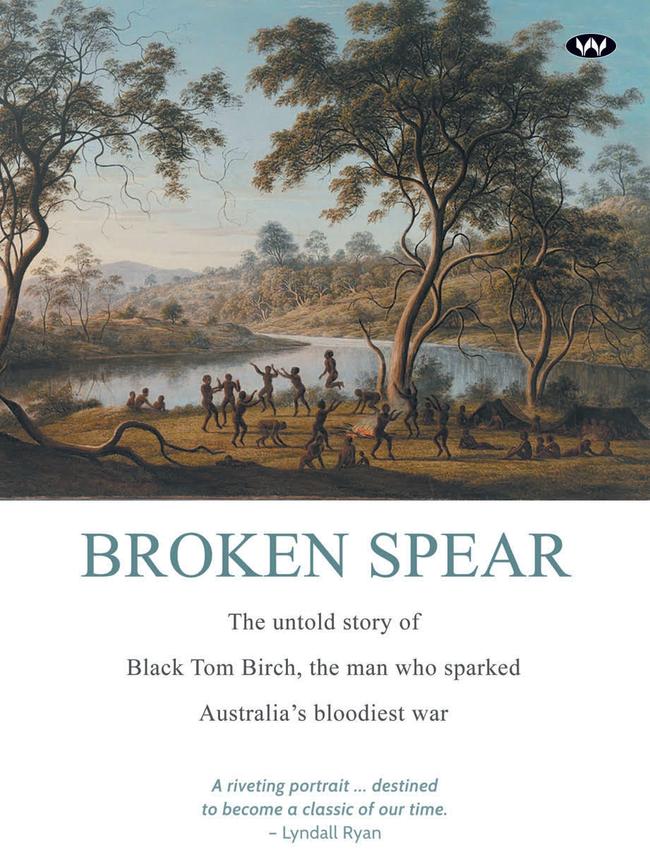

Edited excerpt from Broken Spear: The Untold Story of Black Tom Birch, the Man Who Incited Australia’s Bloodiest War by Robert Cox, Wakefield Press, $39.95

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout