Who was Truganini?

She’s consigned to history as the ‘last of her race’ in Tasmania. But there’s much more to know about this lively, intelligent woman.

Half buried in the sand, uprooted stalks of kelp are like splashes of dark blood against the white quartzite, ground fine as talc. Tendrils of kelp flounce lazily in translucent shallows that gradually deepen to turquoise, turning Prussian blue at the horizon. Beyond the sand, matted tentacles of spongy pigface creep over the dunes to disguise rubbish middens of crayfish, oyster, abalone and scallop shells that have been tens of thousands of years in the making. This beach reclines at the far end of an exquisite body of water in the far south-east corner of Tasmania known as Recherche Bay, so named by the French explorer Bruni D’Entrecasteaux, who rested his ships Recherche and Espérance in the bay during April and May 1792.

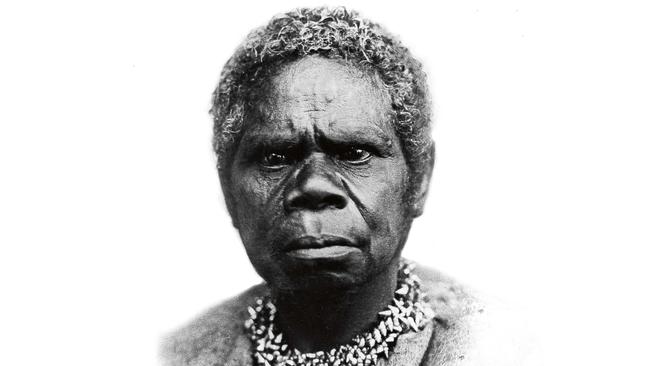

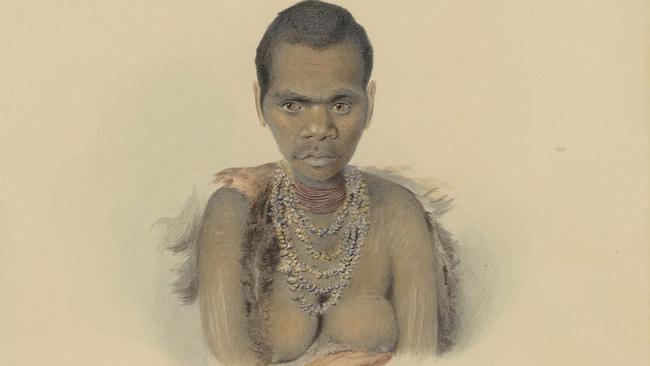

Before the French arrived, this place was called Lyleatea. It was an important ritual site for the Nuenonne, who journeyed in bark canoes from the long offshore island to the north they knew as Lunawanna Alonnah to meet with clans who travelled overland from the west coast. For millennia they made this trip: the same seasonal migration, the same ritual feast. It was during one of these visits – some 20 years after D’Entrecasteaux named this place – that Truganini was born, the youngest daughter of Manganerer, senior man of the Nuenonne. Today, the name Truganini is vaguely familiar to most Australians for having achieved undesired celebrity as “the last of her race”, finding fame when she died in 1876. Her life was much more than a regrettable tragedy. For nearly seven decades she lived through a psychological and cultural shift more extreme than most human imaginations could conjure; she is a hugely significant figure in Australian history.

Truganini compels my own attention and emotional engagement because her story is fundamental to my life story. My great-great-grandfather Richard Pybus was the biggest beneficiary of the expropriation of Truganini’s traditional country of Lunawanna Alonnah, renamed Bruny Island by colonial settlers. For no payment whatsoever, he received well over 2000 hectares of Nuenonne hunting grounds while the original owners of the island were paid with anguish and exile. Early in the 20th century, my great-grandfather William Pybus and his brothers regaled the British collector Ernest Westlake with stories their parents had told about the young Truganini when she was a regular visitor to the Pybus land, where they would give her gifts of tea and sugar, maybe potatoes or damper. Like all Tasmanian schoolchildren, I heard the mawkish tale of the lonely old woman in the black dress and the shell necklace who was “the last Tasmanian”, but no one ever told me of my family connection to Truganini. I left Tasmania when I was nine and never gave her any thought.

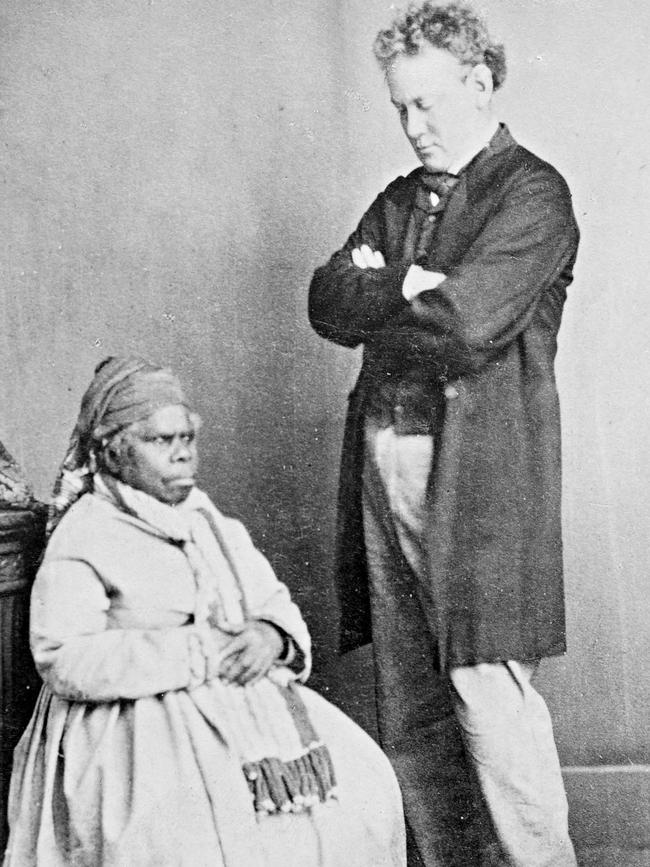

A quarter of a century later, my friend Lyndall Ryan showed me references to my colonial ancestor in the journals of the self-styled missionary George Augustus Robinson, who had a smaller land grant adjacent to Richard Pybus’s. Robinson’s voluminous journals were the catalyst for my first book, written in 1988, the year of the bicentenary of European settlement of Australia. Robinson’s daily devotion to writing in his journal has allowed me a precious glimpse into the lived experience of Truganini, who was his close companion for 13 years. Thanks to him, Truganini is the most documented First Nations actor in colonial Australia. Even so, recovering her life has proved to be a huge challenge. Other than Robinson, few colonial scribblers even noticed Truganini until she died, when the mythologising began. Invariably, she is seen through the prism of colonial imperative: a rueful backward glance at the last tragic victim of an inexorable historical process.

Two craggy fists of land joined by a long, thin neck of sand made up the island of Lunawanna Alonnah, the country of the Nuenonne clan. An extensive coastline provided nesting burrows for the inexhaustible supply of mutton birds that migrated every year from Siberia. Rocky outcrops were perfect nesting sites for equally numerous penguins that migrated from the sub-Antarctic. Undulating forests of bull kelp sprouting from rock ledges along the shore gave protection and nutrition to crayfish and abalone, while oysters and mussels grew in the myriad tidal rock pools. Further out to sea, tiny, barren islands were nurseries for the fur seals the Nuenonne would hunt in ocean-going canoes. Over many millennia, using a regimen of controlled burning, the Nuenonne created large areas of open grassland to support a plentiful population of wallaby. Continually moving from one end of the island to the other along a network of paths, family groups would camp for short periods at certain food-gathering sites. Here they constructed domed shelters made of pliable branches, bark and grass that could accommodate two or three adults with children. Since the beginning of time, it seemed, the Nuenonne had maintained this healthy, happy life, the continuity of people and place uninterrupted by invasion or traumatic upheaval.

Captain James Cook was agreeably surprised on 28 January 1777 when he landed on the beach at Adventure Bay in the HMS Resolution’s longboat to see eight naked men and a boy approaching with the greatest of confidence. Cook was unaware that these people believed they were meeting their own dead returning as pale shades of their former selves. Being treated as some kind of kin, rather than as trespassing aliens, Cook and his officers were not to witness the fierce territorial attachment of the Nuenonne to their country. The British mariners mistakenly supposed the inhabitants were uninterested in the concept of property, and that they were, as the ship’s surgeon wrote, a people with “little to lose or care for”. It was reassuring to believe these guileless people would not mind the expropriation of their territory; to imagine they might not even notice the loss of it.

On the third day of Cook’s visit to Adventure Bay, a larger group of Nuenonne men came down to the beach, joined soon afterwards by a small party of naked women, who allowed their bodies to be examined without the slightest show of modesty. Bodily examination was one thing; penetration was quite another. Every inducement or entreaty for sex from the crew was rebuffed. After an hour of being prodded and stroked, the women retreated into the bush, leaving their men to fall asleep in the sun.

Twenty-five years later, a group of French explorers under Nicolas Baudin came ashore at various points on Lunawanna Alonnah. By then the Nuenonne were no longer “without jealousy of strangers”; they no longer saw the ghost men as their kin. The tranquillity of Nuenonne life had been ruptured by violent incursions from the penal settlement established at Sydney Cove on the east coast of New Holland in 1788. When Baudin and his well-meaning scientists arrived, they immediately noticed that the Nuenonne showed palpable terror at the sight of a musket, keeping a careful distance from the stick that spat fire. Although the French mariners enjoyed some happy interactions with the Nuenonne men, dancing and exchanging songs, no amount of singing and dancing could induce the women to come within arm’s length.

Only a short sail from the northern tip of Lunawanna Alonnah was a wide river estuary where the Nuenonne would often hunt. The British called it Derwent River when they established a second penal settlement in 1804 named Hobart. Many convict and supply ships now sailed past Nuenonne country (Bruny Island) to enter the Derwent. Pretty soon, escaped convicts and deserting seamen came to hide out in the extensive bush cover, bringing with them mayhem and disease. By the time of Truganini’s birth, the Nuenonne clan was diminished and traumatised.

Sometime around 1816, Truganini’s father Manganerer was camped with his wife and three daughters on tiny Partridge Island off Bruny Island, preparing for his seasonal visit to Recherche Bay. By cover of night, a group of sailors stealthily landed in a whaleboat and rushed at the family as they sat around their fire. Manganerer and the children dashed into the safety of the darkness as the sailors held fast to his wife. In the unsteady, feverish light of the fire, Truganini may have seen her mother resisting the sailors with their flailing fists and knives before they vanished into the dark, leaving her ripped body leaking a pool of blood.

In 1818, James Kelly secured a lease for a farm at the northern point of Bruny Island, where he used convict workers to raise poultry and grow grain and vegetables to provision the passing ships. These convicts were alienated and brutalised men, without supervision, and supplied with muskets to hunt the ever-diminishing game – as well as any Nuenonne who might get in their way. Their rations of flour, tea and sugar were used to lure the Nuenonne women for sex. Sealers would appear sporadically, also on the hunt for women. John Baker, an African American sealer commonly known as Black Baker, brought his boat to Bruny Island in 1826. Either with inducements or under the threat of a gun, Baker got Truganini’s two sisters and a third woman into his boat and spirited them away to a life of slavery in the Bass Strait. Truganini never saw her sisters again.

The killing of seals was replaced by the killing of whales. By 1828, there were two whaling stations at Adventure Bay and another at Trumpeter Bay, employing over 80 men. A reciprocal relationship developed between the original people of the island and the men who worked at the whaling stations: in return for sex, whalers would give the Nuenonne flour for damper, plus tea and sugar, for which they had developed an addiction. In this exchange, the motherless Truganini came to appreciate that sexual attraction was a key asset she possessed in the struggle for survival.

Given the desperate situation of the Nuenonne in 1828, it was remarkable that Truganini’s father did not lead his clan to attack the intruders in retaliation for the abduction of their women, the destruction of their food sources and the alienation of their land. The accommodating Nuenonne were a stark contrast to the remnant clans in the “settled districts”, who had taken to engaging in sporadic guerilla warfare against the waves of immigrants from Britain arriving to take advantage of free land grants. The Nuenonne were regarded as role models for what was expected of the original people of the colony: they were unobtrusive, friendly and helpful. The editor of the Hobart Town Courier had been impressed when Manganerer and other senior Nuenonne men persuaded a ship’s captain to take them to Hobart to express to the governor their grievances over the abduction of women and the decimation of game that was their primary food source.

Governor Arthur listened respectfully to the Nuenonne elders, impressed by their intelligence and adaptability. He was something of a rarity in colonial administration in that he was genuinely concerned at the gross injustice being done to the original people of the colony. The great pity was that his humanitarian concerns did not produce humanitarian responses. This well-intentioned governor had his eye on Bruny Island as a potential incubator for a policy of conciliation and civilisation. The man he appointed to be the agent of this policy was George Augustus Robinson, an ambitious tradesman of limited education who had emigrated to the colony in 1824. Remarkably, Robinson gave up his successful trade as a builder to become the butt of derisive jokes as custodian of “the blacks”. He claimed to be solely motivated by a desire “to do them good, to ameliorate their wretched conditions and raise them in the scale of civilisation”.

Truganini was George Augustus Robinson’s first point of contact with the Nuenonne. He found her, in April 1829, living with a gang of convict woodcutters just across the channel from Bruny Island at Birchs Bay. She was a lovely young woman, diminutive and fine-boned, with her hair cut close to her scalp, which emphasised lively dark eyes and a generous mouth. He thought she was about 16 or 17. Impressed with her obvious intelligence and grasp of English, Robinson took it upon himself to take her back to her father on Bruny Island. Robinson was profoundly disturbed by the prevalent carnal exchange between convict workers and local women and he obsessively documented stories of abductions and violence, yet nowhere did he record that Truganini had been abducted. Though he was under no illusions about the brutal nature of the sexual transaction, it was not apparent to him that she was with the woodcutters under duress. It was two years later that she told him how one of the woodcutters had beaten her while others held her down.

He did his best to coax Truganini into being a chaste Christian woman, encouraging her to wear a shapeless smock made from blankets to cover her nakedness. She generally went naked, rather to Robinson’s discomfort. Just as he’d hoped, Truganini’s presence at Missionary Bay encouraged Manganerer to move there with his second wife and young son. A dozen or so demoralised and sick people followed him to receive the daily allowance of half a pound of biscuit and a pound of potatoes that Robinson provided.

Robinson saw the original people as very low in the hierarchy of creation, yet not irredeemable. Instruction in the Christian faith was central to his scheme, as was instruction in the principles of European civilisation, such as wearing clothes, living in houses and growing potatoes. Especially, he wanted to instruct the Nuenonne in the principle of labour. However, most of the women continued to visit the whaling stations, or Kelly’s farm, a practice the men seemed to accept with the same equanimity with which they rebuffed Robinson’s invitation to build huts to live in.

The two or three women who stayed around Missionary Bay spent their days diving for shellfish or collecting wild fruits and ferns, grinding ochre, and treating wallaby skins to make cloaks and small pouches to carry relics of the dead. Truganini liked to collect tiny luminous shells from the beaches, clean them till they shone and string them into exquisite necklaces. She gathered bundles of iris leaves, dried them and twisted the leaves into threads that she plaited and wove into baskets. Truganini was a superb swimmer; watching her diving for shellfish, Robinson could see yet again how critical she would be to his strategy.

He used his dinghy to take Truganini and her friend Dray to places that would otherwise be difficult to reach. The young women would leap from the boat with woven bags around their necks and small sticks, sharpened at one end, clenched between their teeth. They’d dive into the water and lever the abalone shells off the rocks, securing them in their bags. They could stay under for a considerable time before surfacing to take a breath, diving again and again until their bags were full.

In mid September 1829, Manganerer struggled into Missionary Bay in a shocking state. Disaster had struck for a second time on a trip to Recherche Bay. He had encountered convict mutineers who abducted his wife and sailed away with her to New Zealand, then on to Japan and China. Hastily constructing a sturdy canoe, Manganerer had attempted to follow them but had been blown far out into the Southern Ocean. His son had died and he himself was half dead from dehydration when he was found by a whaling ship.

He had endured the murder of his first wife and the abduction of his two older daughters by the intruders; now they had taken his second wife. His only son was dead and in his absence his remaining daughter had run off to the whaling station. His distress was compounded when he discovered that while he was away almost all of his clan had succumbed to disease. It would not be the whalers’ carnal appetites that proved the insurmountable barrier to Robinson’s plans for his civilising mission with the Nuenonne: it was the influenza virus.

Instead of dispensing the fruits of civilisation, Robinson was reduced to an impotent bystander in an apocalyptic nightmare. “Death hath visited with dire havoc,” he confided in his journal, ruefully noting that only 14 Nuenonne remained; these traumatised survivors were slashing their faces and bodies in grief. His evangelical commitment was sorely tested by the daily burial rites, in which he was expected to participate. Traditionally, the Nuenonne burnt their dead and collected the ashes and a bone relic to wear as a ritual keepsake. With so few survivors, the rituals were reduced to a brutal minimum. Missionary Bay became littered with charred remains, some only partly consumed by the fire and subject to the ravages of dogs.

By October, only a handful of people survived at Missionary Bay. Manganerer was barely clinging to life, a broken man. Within a few months he, too, would be dead, from venereal disease.

Robinson had undoubtedly been very taken with Truganini from the first moment he set eyes on her. Whatever desire he felt for her was powerfully tempered by his visceral horror of the venereal disease she had also contracted. He expressed righteous resentment at the sexual liberties taken by other men, but his journals provide no suggestion that Truganini ever became his sexual partner. The role he cast for himself was even more intimate and binding than that of a lover: he was the good father who would protect and save her.

Edited extract from Truganini: Journey Through the Apocalypse by Cassandra Pybus, (Allen & Unwin, $32.99), out March 3

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout