In Broken Spectre, Richard Mosse visits a world of violence and inhumanity in the Amazon

In Broken Spectre, artist Richard Mosse visits a frontier world of violence and inhumanity: the Amazon.

Richard Mosse’s film work The Enclave, shown at the National Gallery of Victoria seven years ago (and reviewed here on December 19, 2015), evoked the murderous insanity of the Congo, a vertiginous hell-hole in which crime, political corruption, ethnic hatred and religious fanaticism had combined to produce a continuous state of savage internecine warfare; 300,000 or so people were dying every year, the population was living in numbed and brutalised state of dissociation and children played next to cadavers in the street.

In Broken Spectre, he visits another frontier world of violence and inhumanity: the Amazon. Here the death-toll is much lower, but the stakes for the whole world are a lot higher. Sadly, it seems to make little difference to anyone outside the Congo if the tribes and gangs there continue to slaughter each other, but the destruction of the Amazonian rainforest is causing serious and possibly irreversible harm to the ecological balance of our whole planet.

Whether fortuitously or by design, Mosse’s film opened in Melbourne the day before the Brazilian general elections, crucial to the future of the Amazon. The first round failed to produce a clear winner, so a runoff vote was scheduled for October 30; I saw the work a week earlier, and the uncertainty of what was to come – before the confirmation of Lula da Silva’s victory – added to the poignancy of watching this evocation of the Amazonian tragedy.

The violence, the corruption and the crime in these tropical nations is of course inseparable from poverty and desperation. In such an environment, economic mismanagement, political incompetence and the breakdown of the institutions of civil society exacerbate each other in a vicious cycle; and anyone who tries to stand for justice or reform is likely to be murdered by those who cannot see beyond their immediate self-interest.

But while we deplore corruption and oppression in principle, we are too often willing to tolerate it in other countries when it suits our own self-interest; and this is not only true of the third world, but of China, Saudi Arabia and the Gulf states among others – countries where it can be dangerous to protest or even to demonstrate.

In our world, we not only take these rights for granted, but trivialise them. The MCA recently advertised an evening with the incongruous title “Pleasure and protest”, described as “an evening celebrating intersectional feminist perspectives, ecosexuality and the body”. One can’t parody this kind of thing: “expect empowering performances… insightful community talks… End your night with a cocktail overlooking the harbour”.

Could anything reek more of smug privilege and self-indulgence? As though the museum were a kind of day spa with discreet erotic services included, one of those places that invites rich women to “pamper themselves”. It is a measure of how disconnected the lifestyle artworld is from reality that it can abuse the word “protest” in this way while women and even schoolgirls are dying in Iran in real protests against real injustice.

Mosse’s film is 75 minutes long, shown on a loop so that the visitor may come in at any point in its unfolding. It is worth watching the whole thing, even though it is a grinding and even draining experience, partly because of the often oppressive soundtrack but mostly because of the dispiriting reality whose various dimensions are gradually revealed.

As with all film works on loops, viewers walk in and out, and few remain for the whole cycle, so that they are left with a general impression rather than a comprehensive understanding of the whole. People seemed nonetheless to be staying for much longer than they usually do, probably because this was a single exhibition rather than one item in the overloaded smorgasboard of a biennale.

I happened to come in at what turned out to be a propitious moment, the closest thing to a beginning or ending in the loop: an Amazonian indigenous woman, standing in front of a group of other tribal members, all in traditional costume, speaks to the camera, addressing then president Jair Bolsonaro and berating him for despoiling the environment and particularly for allowing miners – whom she refers to as his children – to encroach on their traditional lands.

She speaks in short bursts of a few sentences at a time, punctuated with a gesture of asseveration that extends from the arm into the bending forward of the whole body – surely a traditional pattern that may be thousands of years old, for the movements of the body can be almost more durable than language.

She adds, in an aside to the film crew, that she hopes they are not filming her people for nothing. Finally she comes to an end, the tribe applauds, and she stands silent, looking exhausted.

The rest of the film is made up of episodes, mostly in black and white, that document various aspects of the destruction of the environment, interwoven with scenes that appear at first sight more abstract, largely in colour, but which make use of infra-red photography – as in The Enclave – and other techniques, as well as a combination of long shots and close-ups, to convey the degraded state of the environment and the sense of morbid decay in waterways and living ecosystems.

The soundscape alternates between the natural sounds of the forest and oppressive electronic humming, buzzing and thumping effects that evoke the stress suffered by the natural environment.

The first episode after the woman’s speech – the only talking part of the film – shows a demonstration in Brasilia, setting native headdresses and costumes against the modernist forms of the artificial capital, including glimpses of some of Oscar Niemeyer’s famous buildings.

Then suddenly we are watching three men riding on horses through the thick jungle; all seems benign enough until they emerge from the jungle into an area that has been cleared and is now a scene of devastation, a barren wasteland.

For one of the mysteries of the Amazon is that the land is not as fertile as it may seem. The jungle is a lush and stable ecosystem, but unlike the oak forests of Europe, it has not enriched the soil beneath it; once stripped away, the tree cover leaves behind poor and thin soil vulnerable to erosion.

The film cuts to another view of the jungle, seen from the river. Again this seems like pristine jungle, and we even glimpse the silhouette of a jaguar gliding between the trees. Then the view opens out to reveal a tourist’s camera, then another; we are in a small fleet of motorboats taking foreigners on a tour of the Amazonian wilderness.

A following episode begins with shots of what seem like a peasant family, with its children, living in the jungle. But then we realise that the father is crushing ore in a huge mortar and the wife is washing it for gold; these are petty gold-miners, but part of a new gold-rush that is adding to the pressures on the region, and particularly on the lives of the indigenous peoples. Then we see the peasants burning land to clear it, too thoughtless and unconscious of the damage they are doing.

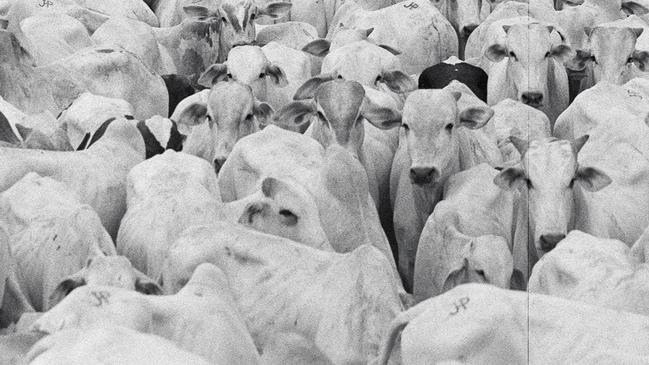

Soon after another episode reveals the horror of the abattoirs that feed modern Brazil. Cattle are herded along a ramp to be slaughtered; the killing is omitted, and we pass at once to the carcases hanging upside down on hooks, being flayed and cut down by workers hardened to feel nothing while carrying out these bloody tasks. Again we are confronted by the obtuseness that is in part a survival adaptation in a world of oppressive poverty.

As though going backwards in the process, we now encounter vast feed-lots, with innumerable cattle feeding from troughs along the edge of the road. There is an interlude to contemplate the festering decay of the river’s life systems, and then we watch workers cutting timber to make fence posts, building fences and stringing wire between them: fields for more cattle in what used to be forest.

A hose spews out water under pressure; we sense this must be gold-mining again, and as the episode unfolds, we discover a blighted landscape of eroded hillsides and sterile mud with no living thing in sight – in fact what much of the Australian goldfields looked like during the gold rush in the 1850s. All around are pools of stagnant, polluted water, poisoned with the mercury used in gold extraction and which, entering the river system, poisons both wildlife and the local people.

Can this get any worse? But then, after another interlude evoking the desolation and toxicity of the environment, we see a man walking through the forest carrying a chainsaw. Soon he is cutting down one of the big trees that is literally like a pillar of the forest, forming an important part of the canopy above and creating the protected climate below in which other smaller plants can flourish, and the next generation of trees can begin to grow.

The soundtrack here is of course the angry buzzing of the chainsaw as it cuts through the timber, and then the crashing of the falling tree, tearing down smaller ones as it falls, and striking the forest floor with a dull thud.

Once again we are confronted with the complexity of the problem: there are big interests at work in some areas, big money and corrupt politicians who profit from it, but there is also an army of poor and greedy little people who will cut trees and even murder activists for money.

More of these men are seen in the following episode lighting fires with torches. They know what they are doing is illegal; they are masked, furtive, scrambling like rats from one bank of bush to another, with their getaway car in the background.

We are left with views of blazing landscapes, massive areas of forest cleared and burning, while the soundtrack is an overwhelming combination of crackling fire with synthetic humming and thumping.

In the remaining scenes, there is more footage of cattle yards, in which we see again a device Mosse uses throughout, a kind of fade transition like a slow form of jump cut, which suggests that we are watching a dream or hallucination. In another scene, a small ball of gold dust and presumably mud is smelted and ends up as a thin sheet of gold, the lamentable price for all this devastation.

And finally, there are scenes of absolutely barren and dead plains, and then open-cut mines, a rare recollection of the larger scale of operations in a film that has concentrated mostly on the micro-level and the actions and experiences of individuals in this environment; and rightly so, because none of this destruction would be possible without stupidity, squalid self-interest and the social conditions that foster such moral and spiritual dereliction.

Richard Mosse: Broken Spectre

National Gallery of Victoria, until April 23

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout