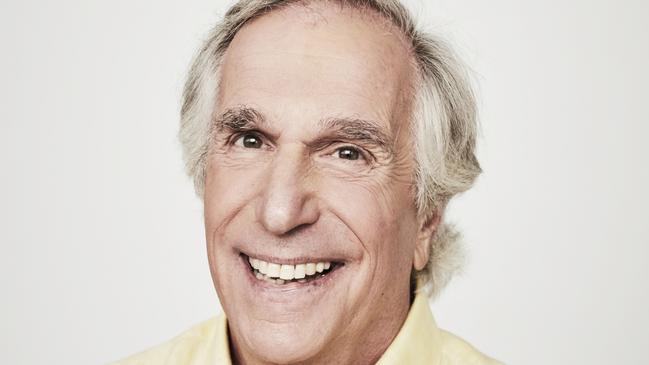

Happy Days star Henry Winkler on fame, grappling with dyslexia and anxiety

As the Fonz, he was once hugely famous. But Henry Winkler was never cool, had a difficult childhood, endured dyslexia and anxiety, and struggled with typecasting after Happy Days.

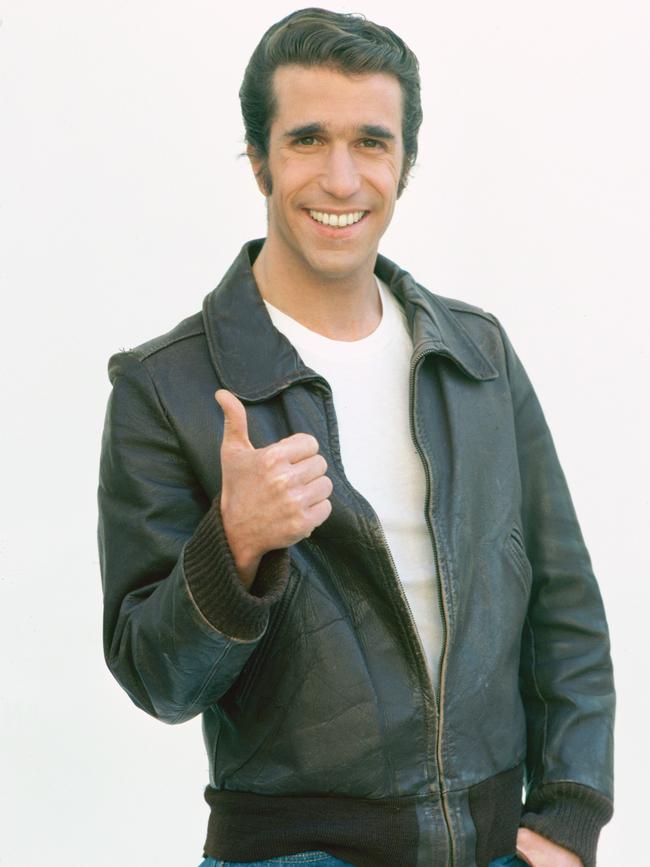

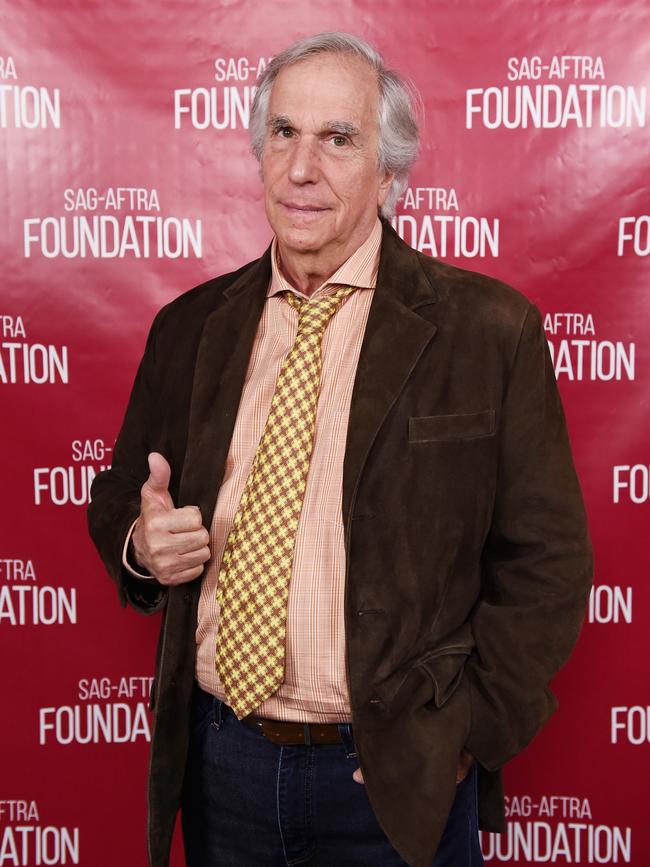

Henry Winkler could not have been more iconic as Fonzi in Happy Days. The leather jacket and blue jeans, motorcycle, the thumbs up, a fist bump that could turn on a light or start a jukebox, a snap of fingers that could make women swoon and communicating with a look or an “Aaayyy”. His image was on T-shirts, posters and lunch boxes. He was synonymous with being cool.

Being Fonzi gave the Yale drama school educated actor fame and fortune but not fulfilment. Plagued by self-doubt growing up in New York, he could not have been more different to Arthur Fonzarelli. He struggled with celebrity. How he managed overbearing Jewish parents, being miserable, dyslexia and typecasting is told in a candid new memoir.

While he had success as a producer and director after Happy Days, and landed roles in Adam Sandler films and shows such as Arrested Development, it was only after earning the role of Gene Cousineau in Barry and winning an Emmy that he felt validated as an actor. At age 78, he finally enjoys being Henry.

As he reflected on his extraordinary journey and shared life wisdom via Zoom, I kept thinking 10-year-old me would not believe who future me is talking to. He could not be more generous, warm or charming. He began by showing me an Indigenous pointing bone he picked up in Alice Springs while in Australia for the Logies in 1976. He loved Australia so much he named his production company Fair Dinkum.

TROY BRAMSTON: The story of your Jewish parents escaping Nazi Germany in 1939, and later hearing of family lost in the Holocaust, is a moving part of the book. You were born just weeks after World War II. How did that family history shape your outlook on life?

HENRY WINKLER: There are people who say, ‘Oh, my parents are my best friends’ or ‘I miss my parents.’ It’s like they’re talking Russian to me. I’m grateful that I’m an American, that they got out of Germany, and I was born here. I’m grateful for a lot of the life that I had, but it was really difficult to deal with them. And so, one of the lessons that I’ve learned is: see who is in front of you. Your children are not extensions of you. See who they are. Hear them.

BRAMSTON: You are open about insecurity and anxiety growing up. Your father wanted you to go into the family lumber business. Do you think he eventually realised that acting was the right path for you?

WINKLER: I imagine he did. They were very proud after I figured out how to be successful. But I have to tell you, I didn’t care. I needed them to be really supportive when everything was so confusing to me, when everything was out of control and when I failed at everything. I promised Stacey, my wife, and myself, that I would be a completely different parent.

BRAMSTON: You write about being “rescued” by psychotherapy. Is there a message for others who may also be dealing with anxiety?

WINKLER: When you are open to growing, to becoming the true person you are, I think therapy is vital in the human condition. I know what it did for me. People say to me, ‘Hey, what is the definition of cool?’ There‘s only one answer: you are cool when you are authentically yourself.

BRAMSTON: Speaking of being cool, you are the opposite of Arthur Fonzarelli in Happy Days (1974-84). How did you deal with being one of the most famous people on the planet?

WINKLER: You know, that’s interesting. First, I was living my dream. Second, I think there is an emotional component to dyslexia, your self-image plummets, and I was able to play the confidence I so madly dreamt about. I got to play who I wanted to be; not who I am.

BRAMSTON: What was it that made Happy Days television magic?

WINKLER: If it ain‘t on the page, it ain’t on the stage. So writing is the beginning and the end. I was given a great character. I had great acting partners: Tom Bosley, Marion Ross, Ron Howard, Don Most, Anson Williams. And (creator/writer) Garry Marshall had us play softball every Sunday. We were a team together and then we were on the sound stage together.

BRAMSTON: You had powerful acting scenes with Ron Howard. Were we seeing Henry and Ron as much as Richie and Fonzie?

WINKLER: He was 18, I was 27. He had been doing film and television all his life. I was trained in the theatre, two completely different upbringings, and yet it was like we were soulmates. In one of the first scenes, I can’t make a joke work. I’m pounding my script. I’m pissed off. I’m having a hard time. And he puts his arm around me, he walks me to the back of the sound stage and he said, ‘I think the writers are working as hard as they can. Maybe we shouldn’t hit our scripts.’ I said, Ron, ‘You’re making perfect sense. I’m out of line.’ And that is the beginning of our relationship.

BRAMSTON: Let me ask you about Fonzi jumping over a shark on water skis wearing a leather jacket. The phase “jumping the shark” has entered popular culture. Is it frustrating because that episode wasn’t the end of Happy Days – there were six more seasons?

WINKLER: No. The young man who thought up the term, Jon Hein, went on to have a board game, he wrote a book and he’s on the radio. Hey, it’s America!

BRAMSTON: After Happy Days, you had success producing, directing and some acting but you were typecast and did not find the roles you wanted. Yet, you later acted in iconic movies such as Scream (1996) and in five films with Adam Sandler, starting with The Waterboy (1998). Tell me about the relationship with Sandler.

WINKLER: I love Adam. He put me in The Chanukah Song (1994). I called him up and said, ‘I just want to thank you. I can’t believe that I’m included in a hit song.’ I went to his house. He plays every sport in the world. I play none. Then he asked me to be in The Waterboy. And that started us on our wonderful relationship.

BRAMSTON: You had later television roles as Barry Zuckerkorn in Arrested Development (2003-19) and Lu Saperstein in Parks and Recreation (2013-15). How was it different to Happy Days?

WINKLER: The tone is different. The writing is different. I cannot be the well-established actor; I have to be the visitor. I was only supposed to be on Arrested Development for two episodes as the family lawyer who knows nothing about the law and who has a questionable sexuality. And I stayed for five years.

BRAMSTON: Winning a Primetime Emmy for Barry (2018-23) seems to have been validating. Why was that so important for you personally and professionally?

WINKLER: What it meant was that I was now part of the history. I was now part of this inner sanctum. It was not so much fulfilling because I still am burning with the same ambition to go on and create something new. But I was thrilled and honoured. If you listen carefully, you can hear the announcer say, ‘This is Henry’s one-thousanth nomination; his first win.’ My tush never left the seat. I was prepared to clap for whoever won and never get up. And my name was called. It was very exciting.

BRAMSTON: I want to ask you this again, Henry, because it does seem in the book that you needed that Emmy. You write about being typecast after Happy Days and although we’ve talked about some of your other projects, it seems that winning that Emmy was particularly important for you.

WINKLER: You know what? It was a validation which I should not have needed. I’m wrestling with this because I am proud of it, but it is a was and I need to make something else that is an is. Does that make sense?

BRAMSTON: Yes, it does.

WINKLER: Yeah, that’s how I’m feeling.

BRAMSTON: You channelled your dyslexia into the book series Hank Zipzer. Is encouraging children to read and supporting literacy programs the coolest thing of all?

WINKLER: That is why Lin (Oliver) and I write our books. We write them for emerging readers, for reluctant readers, because God knows I did not read a book until I was 31. It was so difficult for me when I read the childrens’ bedtime stories. I would fall asleep before they did. So, my wife read them and I acted them out. Hank Zipzer is me. I remember what it was like to fail at everything and want to succeed.

BRAMSTON: You write that you realised “things come in their own time” and that living, growing, being is the key. Is that a lesson for everyone?

WINKLER: If there is one thing I learned in my journey, one thing that they can take away, it is that the more you give up being frightened that if you change, the world changes or that people won‘t like you, or it’s too frightening to do that. The more you do change, the air is sweeter, just breathing is more delightful. It is very powerful.

Henry Winkler’s Being Henry: The Fonz … and Beyond is published by Pan Macmillan. This interview has been edited.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout