Solo: A Star Wars Story, Ron Howard, George Lucas, Lawrence Kasdan

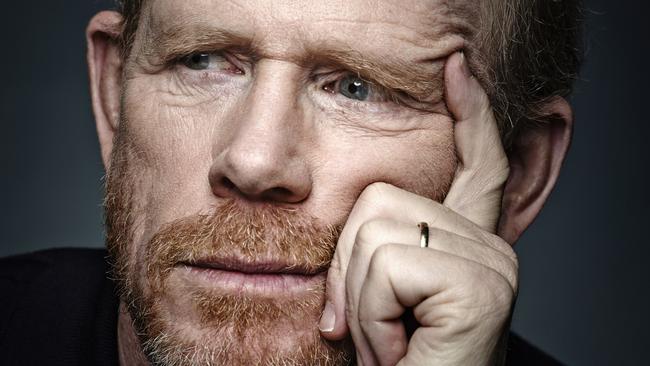

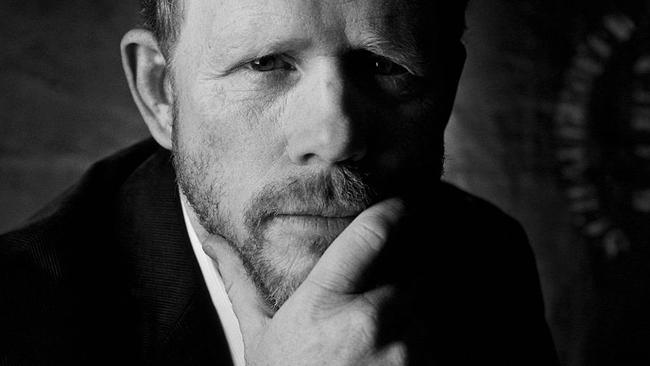

Director Ron Howard’s long friendship with George Lucas finally convinced him to dive into the Star Wars firmament.

Ron Howard has to keep his cards close to his chest when he’s talking about the latest instalment in the Star Wars universe. There’s only so much he can say ahead of the release of Solo, the origin story of the Millennium Falcon’s cavalier captain.

One thing he can reveal about the action, however, might come as a surprise. “It’s cool, cutting-edge, it’s got a little bit of a 70s vibe, almost like a car culture vibe, Bullitt maybe.”

Howard had his own 70s car-culture moment of a very different kind when he starred in George Lucas’s 1973 music-driven coming-of-age movie American Graffiti, spending much of his time at the wheel of a white 1958 Chevy Impala. It was the beginning of their friendship: he went on to direct Willow (1988), Lucas’s tale of magic, sorcery and special effects, and they stayed in touch through the years.

Now Howard is directing Solo: A Star Wars Story, which premieres out of competition at the Cannes Film Festival on Tuesday, just ahead of its worldwide release.

He took on the job under uncomfortable circumstances, stepping in mid-production when the original directing team was removed. Lucas is not part of the creative team on Solo, but Howard says their friendship “was definitely a factor” in his agreeing to direct the film.

“I’ve never been particularly interested myself in tackling a Star Wars movie, even though I’m a lifelong fan and I’ve always been rooting for them because of my relationship with George,” he says. “And I’ve seen behind the curtain a good deal, I have an idea of just how challenging the movies are to make.

“But when this opportunity came along, [because of] my old friendship with George, my friendship with Kathy Kennedy [president of Lucasfilm, and the figure at the apex of the Star Wars franchise], there was something about it that felt right.” Solo — like Rogue One (2016) — stands apart from the Star Wars trilogies. Rogue One created an entirely new set of characters, but Solo is a different kind of challenge: presenting existing characters in new incarnations. In the film, Han Solo is a work in progress, a cocky yet accident-prone youngster who has been on the streets since the age of 10 and is convinced he will be the greatest pilot in the universe.

In Star Wars (1977), Solo was an adventurer with a backstory. There were references to a debt to crime kingpin Jabba the Hutt, and a bounty hunter on his trail. In the next film, The Empire Strikes Back (1980), we met one of his old friends, the first owner of the Falcon, gambler Lando Calrissian (Billy Dee Williams), who went on to betray Solo, then had a change of heart and joined forces with the rebels.

The plot of Solo is a closely guarded secret, but some elements of the backstory are clearly in play, judging from the trailers: there’s a suave Lando Calrissian, played by Donald Glover; Chewbacca is there, played by Finnish actor and ex-basketballer Joonas Suotamo. He has already played the role in The Force Awakens (2015) and The Last Jedi (2017).

There’s no sign of Jabba the Hutt or bounty hunter Boba Fett, and no one at Lucasfilm is saying anything one way or the other, but it’s hard to believe they won’t be part of the storyline. The trailers have also introduced some new characters, including: Solo’s partner in crime Qi’Ra (Emilia Clarke from Game of Thrones); a criminal mentor, Tobias Beckett (Woody Harrelson); and a droid called L3-37, played by Phoebe Waller-Bridge of Fleabag.

Another of the key decision-makers in the Star Wars galaxy is filmmaker Lawrence Kasdan. He wrote The Empire Strikes Back and Return of the Jedi (1983), co-wrote The Force Awakens and, with his son Jonathan Kasdan, wrote the screenplay for Solo.

Some fans’ expectations about the backstory are likely to be fulfilled in the film, Howard says.

“What’s really inspired about the Kasdan screenplay is that it doesn’t fill in all of them, of course, but the boxes that it ticks, it does in a way that’s very satisfying, and they feel right, and they’re surprising — there’s more there than you would expect. That’s where a lot of the entertainment value is.

“But the action is also always addressing the question: how does this test Han? How did it shape him? How does the action of this crazy tense action set-piece impact him? I thought it was really ingenious, the way it created this defining adventure story focusing on Han.”

It wasn’t easy, he says, stepping in mid-movie, when directing team Phil Lord and Chris Miller (The Lego Movie, the Jump Street series) were removed from the film in June last year.

Variety reported at the time that “it was a culture clash from day one”: that Lawrence Kasdan and Kennedy found the pair’s way of working too loose, and Miller and Lord chafed against Disney’s and Lucasfilm’s need for tight control.

Howard chooses his words carefully. “I don’t want to go into it too much, but it was a classic case of creative differences if ever there was one. I wasn’t around, I didn’t witness it, didn’t delve into it too much,” he says.

“But by the time I came on board, that difference of opinion had left the producers in a situation where there were already some scenes they knew they wanted to see approached in a different way. I saw those scenes and agreed to that. And then there was a lot of other work we agreed was everything that it should be, and it was great — a sense of fun and a comedy vibe that I wanted to preserve. Everybody did.

“There was a period of discussion about what was left to be shot, and some things that the producers and the studio were interested in trying to get ... I was encouraged to bring my fresh ideas to the whole process, which was welcomed, and the Kasdans rolled up their sleeves, and we incorporated the ideas of mine that seemed to hold up and make sense.”

In most of the films he has directed, Howard has been closely involved in development.

“There have only been a few instances in my career when I came into a project that I hadn’t developed over a period of months or years and just liked the script enough to say: ‘I’m in.’ I’d always begin to contribute, but basically I didn’t have to go through some sort of trial period.

“Two of those were Peter Morgan scripts, Frost/Nixon and Rush, where I read them and jumped in. I felt that way about A Beautiful Mind, when I read that script. It’s a rare thing when that happens.

“But I felt that way about this script, otherwise I probably wouldn’t have come in.”

Before Solo was cast, plenty of names were considered for the role: actors reportedly in the frame included Scott Eastwood, Miles Teller, Dave Franco and Ansel Elgort.

Alden Ehrenreich, who landed the part, is probably best known for a wonderful performance in the Coen brothers’ 1950s Hollywood comedy Hail, Caesar! (2016) as a guileless singing cowboy cast in an elegant drawing room drama whose dialogue he can’t master.

He featured in another Hollywood period piece, Warren Beatty’s portrait of Howard Hughes, Rules Don’t Apply (2016), as Hughes’s ambitious driver.

According to Hollywood Reporter, Lucasfilm had concerns about Ehrenreich’s performance and found an acting coach for him: this happened before Howard signed on to the film. The director describes him as “a very thoughtful, very intelligent and well-trained young actor with a lot of range”.

“He’s got great comedic timing, he’s very soulful, he understands and is interested in all the ways that a movie like Solo and a character like Han can entertain an audience, and he’s into it, he’s not trying to push it one way or another. He is a great team player and sets a great example, even at his young age, as the lead of the movie. His work ethic was fantastic. He understood how to capture that swagger that Han Solo also has to have — but underneath it there is that soulfulness, there’s that vulnerability. What makes a lot of the characters that George Lucas created really work is that they’re more psychologically complicated than you’d think for an action-adventure space opera.

“And here’s one thing: Harrison Ford never had to carry a movie as Han Solo. This is a challenge and an opportunity to drill down and focus on young Han, at a time when he’s not his own man. He can’t be the free spirit, this is about him trying to break through an environment that’s repressive, restrictive and try to be free and be his own man and define himself.”

Howard took the opportunity to talk briefly to Lucas before he started on the film.

“He was very supportive when I came in, he said: ‘You’re going to find yourself very comfortable once you get in the midst of it. Just trust your instincts.’

“We didn’t talk too much about Han, although he did visit on the first day of shooting when we were doing a very funny scene between Alden and Emilia Clarke, where Han is full of swagger and bluster and charm.

“There was one bit of business we were working on that wasn’t scripted, where Alden and I were kind of inventing this moment, and George was watching it, and he was just there to support, but then he said, ‘Of course Han wouldn’t do this, he would actually do that’, and we said: ‘Oh well, we want Han to do that’ — and it’s what Alden did, and it definitely took the scene up another notch.”

Ford — who, as it happened, had a small role in American Graffiti — was also consulted.

“I had the good fortune to be able to give Harrison a call and talk to him a bit, and it was very interesting,” Howard says. “Alden had had a dinner with him, set up by Kathy Kennedy at Alden’s request, and Harrison had been great and supportive, but he hadn’t really offered a lot of insight.

“I asked Harrison about that when I got on the phone, and he said: ‘Well, Alden is an incredibly talented and bright actor, I didn’t want to impose my perspective on the character. To be honest, I want him to find Han Solo, it shouldn’t be an imitation.’

“I said: ‘It’s not, no one thinks it should be, starting with Alden. But talk to me, I’m coming in and directing, and you’re a real thinking actor, just talk about the character.’

“He gave me about 20 minutes, and I took notes, and found it incredibly useful and surprising ... Harrison is so thoughtful, of course he had some interesting insights that I wouldn’t have necessarily thought of on my own. And it was useful to me, not only shooting and staging the scenes, but also occasionally guiding Alden through a moment or a scene.”

Howard comes from an acting family: he started out as a child actor in the late 1950s before landing a role in a long-running sitcom, The Andy Griffith Show, as the precocious son of a small-town sheriff. Between 1974 and 1984 — when he played all-American boy Richie Cunningham in Happy Days — he was also looking to work as a director.

He got his first break through Roger Corman, the legendary B-movie producer and director who gave early opportunities to Martin Scorsese, Peter Bogdanovich, Francis Ford Coppola and Jonathan Demme, among others.

Howard approached Corman with a script he and his father had written. Rather than make this film, Corman made Howard another offer: if he appeared in a 1976 car-chase comedy, Eat My Dust, he would be given the chance to direct and star in another movie.

Eventually Corman told him that if he could come up with an idea for a car-crash movie, to be called Grand Theft Auto — a title that had tested well — he would be given the opportunity to direct. Howard took his chance, came up with an outline almost immediately, shot the movie on a tiny budget, and turned in a hit.

He followed this with some TV movies, then the 1982 comedy Night Shift, starring his Happy Days co-star Henry Winkler. He has moved between comedy and drama, with titles including Splash, Parenthood, Apollo 13 and The Da Vinci Code. He won Oscars for best picture and best director for A Beautiful Mind, and was nominated for Frost/Nixon.

Taking on Solo is a risk and a responsibility, he says, “but I couldn’t paralyse myself with worrying about that”.

He recalls the recent experience of making The Beatles: Eight Days a Week — A Touring Documentary. It tells the story of the band’s life on the road from 1963 to 1966, combining archival material with found footage and new interviews.

“It was a creative challenge I wanted to meet,” Howard says. “Then when word hit the internet that I was directing a Beatles documentary”, he said to himself: “Oh my lord, you idiot, Ron, you’re not just making a documentary, this is the Beatles. And this really matters, and it should.”

Returning to Star Wars, he says: “Not that I was glib about it going in, but I certainly realised there was going to be another level of scrutiny when I signed on to Solo.

“But these movies are for the fans. I think that everybody involved brings as much of themselves to the project as they can.

“But they’re always in the service of this great set of characters and the Star Wars legacy and that relationship the fans have with it.”

Solo: A Star Wars Story is released in Australia on May 24.