Good art should speak for itself: The National, review, 2021

A vague premise and convoluted artist statements hinder this exhibition of varying quality

What is the purpose of an exhibition such as the ambitiously titled The National? The same question could be asked about any of the lumbering collective exhibitions of contemporary art of the biennale type, but the extra out-of-season ones such as this and Melbourne Now seem particularly gratuitous. From one point of view, they are simply lazy ways to fill up the exhibition calendar with a grab-bag of artists that curators want to promote. There is certainly nothing scholarly about them, and they can’t be aesthetically coherent since they always involve a disparate set of artists and work that is almost deliberately heterogeneous.

On the other hand they are also almost comically predictable, particularly in what they exclude. As I write, for example, several well-known painters have exhibitions in leading commercial galleries in Sydney, but it is unimaginable that their work would ever be included in a show such as The National; the contemporary art establishment and its clique of curators are like the popular girls at school who define themselves as cool mainly by excluding nonconformists.

Although in reality group exhibitions of this kind are promotional and opportunistic, they seek to conceal this behind elaborate yet nebulous moral and quasi-political claims – the kind of cultural politics that is essentially a matter of symbolism and self-positioning, like the attachment of popular girls to the right brands, and very little about making real changes or dealing with substantial and urgent problems. These are the people who would much rather describe the arrival of European settlers as an invasion than do anything about providing work, education and opportunity for Aboriginal Australians.

So it is worth looking more closely at the claims that are made for the three parts of this exhibition, each of which purports to have a slightly different rationale.

The Art Gallery of NSW, according to its website, “presents 14 artist projects that explore the potential of art to heal and care for fragile natural and social ecosystems. In considering our relationship to sentient Country, as both a concept and lived experience, these works engender an attentiveness in and about the world.”

Hiding behind the usual hedging and vagueness implied by the noncommittal expression “exploring the potential”, there is the question-begging suggestion that something called “art” can “heal and care for” the natural environment – not to mention “social ecosystems”.

What does this actually mean? Art is not capable in itself of doing anything to the natural environment. What it may do is to raise our awareness of the beauty and indeed sacredness of nature, and thus encourage us to reflect on the way we live. But this kind of awareness is better fostered by some of the work that the popular girls instinctively exclude.

And what are we to make of the expression “sentient Country”? Merely to use the word country without a definite or indefinite article is, in Australia, to perform a smug act of ritual genuflection to Aboriginal culture. But sentient? Are the authors of this text asserting that the natural world is endowed with consciousness? Do they believe this? Of course not. The text is just another expression of a culture in which language is employed for superficial and ultimately cynical effect and never critically held to account.

Carriageworks “presents 13 artist projects that place an emphasis on collaboration, kinship and sociality, with artists navigating the measure and texture of our actions and engagement with the world around us”.

In the first part of this proposition, the idea of collaboration is packaged in the woolly expression “place an emphasis on” and followed by two other nouns that blur rather than sharpen focus on the concept. In the second part, the shopworn metaphor “navigating” (a variation on “explore”) is followed by the unintelligible doublet of “measure and texture”, which typically muffles and confuses the potentially concrete word “actions”.

Bad style, as George Orwell pointed out long ago, has moral and political consequences: and the reason this kind of writing is so woolly is that it is hypocritical, just like the black pages acknowledging traditional Aboriginal ownership of the land that visitors to museum websites today have to click past to get to the sites themselves: formulaic acknowledgments are hypocritical because they are meaningless and self-indulgent substitutes for real concern and action. And writing about navigating the texture of our engagement with the world is claiming credit for ecological sensibility while making any thought of action inconceivable.

At the Museum of Contemporary Art, “Thirteen artists consider diverse approaches to the environment, storytelling and intergenerational learning … Drawing on natural materials and processes, as well as found objects and detritus, they explore notions of planetary caretaking, and our relationship to place in an era of dramatic change”. Here too the words “storytelling” and “intergenerational”, like “kinship” at Carriageworks, are another coded reference to Aboriginal culture, which in the past decade or two has come to be a compulsory, if ill-matched twin of official contemporary art.

Again “planetary caretaking”, a laudable idea clothed in an unfortunate form of words, is preceded by “notions”, which has been for three or four decades one of the vaguest terms in the jargon of contemporary art’s copywriters: no one really knows what a notion is, except that it appears to be the vague form of an idea or the larval and immature anticipation of a concept.

There is much more in the MCA blurb, but most amusing is the celebration of termite mounds as a symbol of cohabitation and symbiosis: unfortunately the symbiosis of ants and termites takes the form of the former eating the latter.

Divided between three galleries, the exhibition takes at least a half-day to visit, which is asking a lot for the paucity of the reward. This time I took the train to Redfern to visit Carriageworks first. It was early afternoon on Sunday and the place felt deserted; three or four other visitors wandered around while I was there. The exhibition was unimpressive and indeed, as subsequent visits to the other two galleries proved, the worst of the three.

Much of the work at Carriageworks was insubstantial or ill-digested, as though the artists had never acquired the discipline and sense of form and organisation that come from mastering a specific art form, with its range of techniques, history and sets of expectations. Shapeless and unresolved work is not imaginatively communicative or engaging, and loading it with extraneous political and philosophical commentary in the label makes the weakness at the heart of the work only more blatant.

One of the only works to have the kind of shape and resolution that come from discipline and training is the film by Vernon Ah Kee and Dalisa Pigram. Unfortunately, neither the quality of the film nor that of the performance could compensate for the predictability and banality of political slogans we have heard a thousand times before. Another Aboriginal film made by a collective included footage from a Four Corners documentary and seemed to be complaining about children removed from dysfunctional homes in remote communities.

A second train ride took me to Circular Quay where it was immediately apparent that the MCA exhibition and its curation were of far superior quality. The show opened with an impressive joint display of John Wolseley and the late Mulkun Wirrpanda, who died in February, sadly. Mulkun was a practitioner of bark painting, a stronger and more authentic tradition than some other forms of Aboriginal art that have had enormous financial success in the art market. Wolseley’s work, too, has always been inspired by nature and the processes of life, which he evokes in complex collages of prints in various media as well as watercolours on sheets of paper that have sometimes been patterned through charcoal frottage.

At the other end of the gallery is a striking collection of work by Deborah Kelly, all of which purports to be part of the promotion of an alternative religious movement – surreal, burlesque and camp – under the title of Creation. There are painted and collaged designs, exuberant and erotic with an emphasis on open mouths, sensual lips and long legs; the most prominent part of the exhibition is a series of large-scale projections of dancing puppet-like collaged figures.

Sally Smart, too, has an ambitious work that consists of a projection of dancing figures over a large-scale collage that includes pictures of the dancers, in front of which puppets are suspended. Lauren Berkowitz has made assemblages out of salvaged ocean plastic, reminding us of one of the ugliest aspects of the despoliation of our environment. But most intriguing perhaps are Caroline Rothwell’s digital animations based on charcoal drawings, which more than any other work in the exhibition evoke a real sense of the life and livingness of nature.

The MCA was far livelier than Carriageworks, and full of visitors. Walking over the Art Gallery of NSW, the ambience was much less animated. The place has felt tired and uninspired for years, and this was no exception. The quality of the work and the curation here was inferior to the MCA, although still better than the dismal spectacle at Carriageworks.

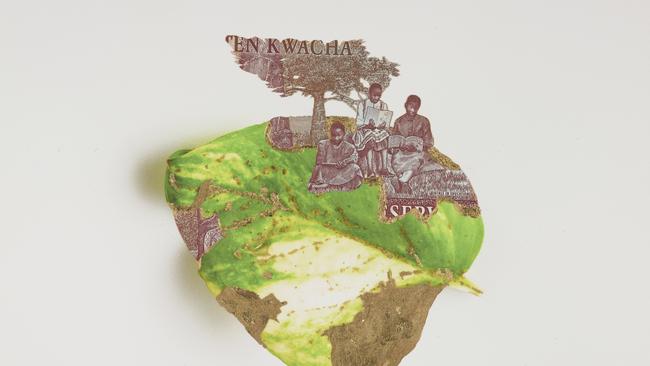

The works on the entrance level are fairly indifferent: a set of rings made of charcoal is almost interesting but ultimately fails to resonate. The rest of the work is two floors down; most of it is also fairly indifferent, but Abdullah MI Syed stands out: several suites of work are united as part of a homage to his mother, including a moving film sequence in which the artist re-enacts the domestic tasks and rituals that were part of her daily life. Another installation is composed of objects that belonged to her and a third on photographs of damaged leaves culled from her money plants that have been repaired with gold leaf and collaged with images cut from banknotes.

Gabriella Hirst’s Darling Darling, which premiered at ACMI and was reviewed here a few weeks ago, is less effectively installed at the AGNSW than in Melbourne, and once again accompanied by heavy-handed and tendentious commentary. The contemporary art curatorium never trusts audiences to be intelligent enough to draw their own conclusions, or perhaps they are simply afraid that they won’t draw the right ones.

In any case, the label assures us that “Hirst draws attention to the role of institutions, like the Gallery, that are the by-products of the same colonial ideology that has wreaked havoc on First Nations’ people, culture and country”.

What might that so-called colonial ideology be? No matter, the gallery has clearly learned its lesson, which is why it is spending so much money healing and caring for the natural environment by erecting a vast concrete convention centre on what used to be unoccupied neighbouring parkland.

The National

Art Gallery of NSW, Museum of Contemporary Art and

Carriageworks, Sydney

Until September 5

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout