German precision revealed in Fred Kruger's landscape photography

A COUPLE of recent exhibitions have recalled the part Germans played in the history of Australia.

A COUPLE of recent exhibitions have recalled the part Germans played in the history of Australia, especially during the first half of the nation's short history.

The Enemy at Home (reviewed here in August last year), at the Museum of Sydney, revealed a remarkable collection of photographs made in the concentration camps where Germans were held as enemy aliens during World War I - and in the process reminded us that Germans were once the most important non-British part of the Australian population.

It was in the aftermath of World War II that Australia's ethnic composition, and eventually also its cultural tone, were profoundly changed by the influx of Mediterranean immigrants, mainly from Italy and Greece, but also from regions such as the former Yugoslavia and Malta. At the turn of the last century, there were relatively few southern Europeans, but about 100,000 Germans, many of whom were concentrated in areas such as South Australia, where German was spoken and German religious and cultural traditions followed.

Germans were distinguished in many fields of Australian life, from industry and agriculture - particularly viticulture - to scholarly life and missionary activity; until after the Great War, when a large number were deported and others left voluntarily, discouraged by the new mood of xenophobia among British-Australians. Their prominence in mid-19th century Melbourne was particularly notable, as we can hardly fail to notice in the outstanding Eugene von Guerard exhibition that originated at the National Gallery of Victoria and opened this week at the National Gallery of Australia in Canberra.

Melbourne was a new city in the mid-19th century, fuelled by the wealth of the gold rush, but rapidly building a cultural and scientific infrastructure of museums, libraries and a university only slightly younger than Sydney's. And the remarkable fact is that most of the important scientists were Germans, including Ferdinand von Mueller, the great botanist; Georg von Neumayer, a geophysicist; Wilhelm Blandowski, the founding curator of the Museum of Natural History; Gerard Krefft, a zoologist; and Ludwig Becker, artist and geologist.

Many of them, such as von Guerard, were inspired by the teaching of Alexander von Humboldt, one of the intellectual giants of the age, who urged scientists and artists to explore the vast areas of the world that remained to be properly studied by geologists and natural historians.

But this was a different Germany from the one that emerged later and gradually succumbed to the militarism that led the nation from the catastrophe of one world war to the horror of Nazism and the new disaster of World War II. Germany in the middle of the 19th century was still a collection of separate kingdoms and tiny principalities; the greatest of Germanic states, and the traditional leader of the German world, was Austria, but Prussia, far to the north, had established itself as a great power in the 18th century under Frederick the Great, and it was the British and Prussians together who ultimately defeated Napoleon. When German unification came in 1870, Prussia instigated the process and dominated the new nation, excluding Austria, which it had already defeated in the Austro-Prussian war of 1866.

The Germans in Melbourne belonged to what was still a politically and socially diverse people, and at the same time an artistic and scholarly tradition that was unsurpassed across the world.

German culture, which had been intellectually provincial for centuries, had blossomed into a golden age in the romantic period, renewing the language itself, establishing the standards of modern scholarship in areas as diverse as science, philosophy and philology, and reaffirming its absolute primacy in music. The momentum established early in the new century continued on into and beyond the period of unification, and as we saw in yet another exhibition with a German focus, The Mad Square, was still remarkable even in the shattered social fabric of the Weimar Republic.

Fred Kruger, whose photographs are shown in a comprehensive survey for the first time at the NGV, also came from this renascent Germany; unlike the aristocratic Humboldt and most of the German scientists in Melbourne, however, his background was a working-class one. He was born, as we learn from the fine catalogue by Isobel Crombie, in 1831 and grew up in Berlin, but his father, who was an unskilled worker, died in 1837 when Fred was only a little boy. It is unclear how his mother survived with four children under the age of six, but Fred grew up, married in 1858 and worked as an upholsterer. In 1860 he immigrated to Australia, joining his two brothers already here. His wife joined him two years later.

Initially he joined his brother Bernhard in an upholstery and furniture business in Rutherglen, northeastern Victoria, but as the alluvial gold ran out, the profitability of their venture declined, and Kruger sold up and moved elsewhere. He continued working in upholstery for a time but was forced into bankruptcy, before emerging soon afterwards, without any clear evidence as to how he learnt the trade, as a photographer.

Crombie paints a fascinating and poignant picture - based on limited documentary resources - of an artist's career: of the separate courses of a personal life marked by repeated bereavement, as child after child was born and then died in infancy, and of a professional existence pursued with energy and determination. The vicissitudes of the personal life seem to be reflected in regular and restless changes of domicile, while the continuity of the professional practice is manifest not only in a steady production of images, sold separately or in albums, but an ambitious participation in national and especially international exhibitions from Paris to India, in which he was frequently awarded medals and other prizes.

While the pictures were sent far and wide across the world, Kruger himself travelled through the Victorian countryside with his horse-drawn photographic van, including a portable darkroom, which allowed him to take and develop images as he went. He was thus able to carry out documentary commissions from government authorities, respond to local opportunities for portraits of properties in the places that he visited and take images he would sell on his own account.

The aesthetic of the landscape views is quite a distinctive one, in which one can sense affinities with both of the great contemporary landscape painters in Victoria, his fellow German von Guerard and Swiss Abram Louis Buvelot. The clarity and quiet impersonal quality of some of the images recall von Guerard, but Kruger's general preference for a closer point of view and a more intimate relation to the motif, including rivers and groups of trees, recalls the new style, associated with the Barbizon school, that had been introduced by Buvelot.

As Crombie rightly points out, Kruger sees the Victorian countryside through the eyes of a man who had grown up in mid-19th century Berlin, a dirty and crowded city affected by deadly epidemics - one of which may have carried off his own father - and social tensions. Like many Europeans of his time and after him, he must have been impressed by the sheer space and openness of Australia, which offered opportunities to make a new life, to become prosperous through enterprise and to enjoy solitude and communion with nature.

The pleasure of simply being in the country, far from the noise and disturbance of the city, is palpable in pictures such as View on the Barwon River (circa 1880), with its single tiny fisherman silhouetted against the white surface of the river, surrounded by gnarled gum trees. In another image, a man stands in admiration before a waterfall, an excursionist, as the expression was, on a daytrip, rather than an explorer. Water animates a landscape pictorially as well as literally giving life to the soil, especially in a dry country such as Australia, and in Kruger's pictures it contributes importantly to the sense of tranquil wellbeing that he suggests.

Kruger does document the progress of human occupation of the land, particularly in the building of bridges - a theme of perennial interest and particularly in relation to his love of rivers - but man's presence in these landscapes always seems to be light, and to our eyes, a century and half later, many of his views speak of an almost pristine nature into which a few human structures have been delicately placed without disturbing the rest of the environment.

There is something particularly poetic about boats in this respect, which are not permanent structures but simply the vessels in which we move around waterways. A curious image, discussed in the book, shows a party of men and women enjoying a day on the bank of a creek, although their faces have been scratched out on the negative. Subsequently, Kruger printed another version in which this foreground is omitted and the focus moves to the wooden dinghies on the far side of the creek and the view beyond; apart from a tiny hut, the coastal landscape seems barely touched by settlement.

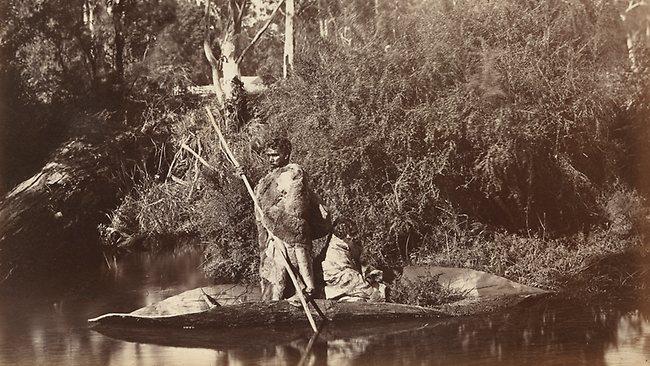

Kruger was well aware of the Aborigines, although they never seem to figure in the landscapes discussed thus far. He was commissioned to take documentary photographs at Coranderrk Aboriginal Station, however, and the resulting images are fascinating and complex. In most of the pictures he does not focus on the exoticism of his subjects but on their integration as members of a modern society.

In a few cases, he has them dress in traditional costumes for pictures that are rather self-conscious historical reconstructions, and in one remarkable pair of photographs we encounter the same family in Victorian dress and then wrapped in possum-skin coats and blankets. There are many images of the colonial urban world as well, which are of great historical interest although less aesthetically engaging than the landscapes; and there are a few other images in which Kruger deals explicitly with history, or at least with contemporary events. One of these shows the arrest of a man caught illegally scavenging from a shipwreck. There is something rather melodramatic about the scene, and we realise that it is because it is posed, as the shutter speed of the camera was still not sufficient to capture figures in motion; in another picture, a moving dog becomes a white blur.

This realisation makes us look more closely at any image that purports to represent movement. In the picture already mentioned that was so oddly disfigured before being cropped, there was a detail of a man passing a bottle to another man. Whereas a Cartier-Bresson could snap such an action as it happened, and use it to animate a scene and bring a composition together, photographers of Kruger's generation had to stage their decisive moments, and every action was in fact a re-enactment.

Fred Kruger: Intimate Landscapes

Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia, Melbourne, to May 27