Faith, freedom and Scott Marsh’s mural of Saint George Michael

This image is not just a street mural depicting British pop icon George Michael ... it’s a battleground for love and hate and a story of finding a second life on stage.

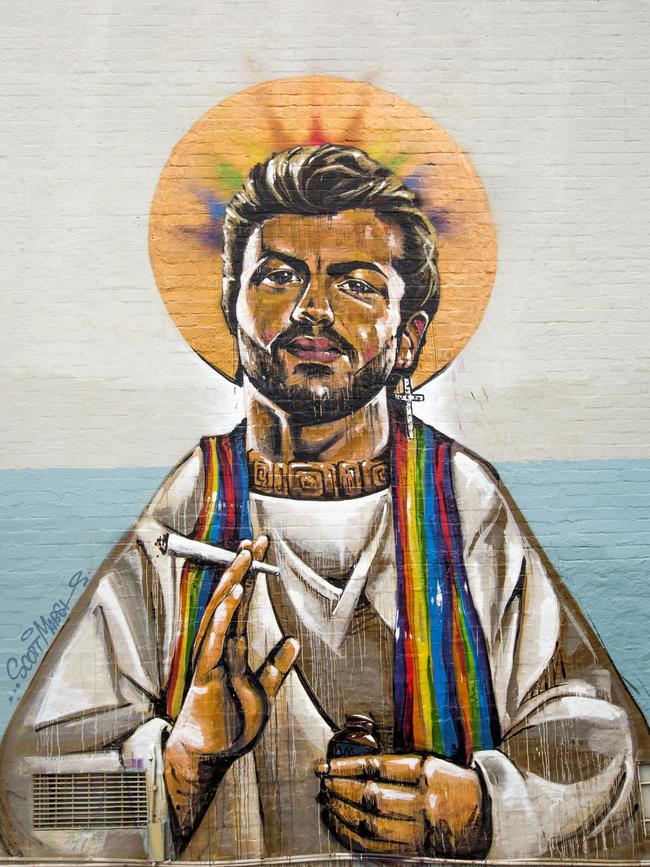

For nearly a year, George Michael’s serene face smiled out at passing pedestrians, cars and passenger trains, a lit joint in his right hand and a bottle of amyl nitrate in the other: two mind-altering offerings from a prince of pop music reimagined as a saint by a cheeky street artist.

Painted on to the side of a multistorey home in the inner-western Sydney suburb of Erskineville, the much-larger-than-life mural depicted the British singer-songwriter clad in white robes and a rainbow sash, complete with a sparkling crucifix hanging from his left ear and a halo that shone coloured beams of light behind his perfectly coiffured hair.

This was no random act of celebrity worship. Instead, it was a heartfelt tribute to a departed friend commissioned by the two housemates on the other side of the mural, who were prominent members of Sydney’s queer community and dance music scene: Paul Mac and Jonny Seymour, who perform as the DJ and remix duo Stereogamous. Together, the three artists had bonded over a shared love of music that had been apparent from their first meeting in a Sydney hotel room in early 2010, when Michael was visiting Australia for a three-date stadium tour.

Their connection on that first night was so strong that the touring artist immediately commissioned Stereogamous to make a 30-minute playlist to precede his performance before more than 40,000 fans at the Sydney Football Stadium the following night, bumping the other DJ from their warm-up slot.

In short order, Mac and Seymour showed Michael the city’s annual Gay & Lesbian Mardi Gras parade, where dozens of fit young men dressed up as the British singer to perform a choreographed dance routine down Oxford Street.

He was so moved by the abundant love on display that he returned the favour to the community by making an appearance at the Mardi Gras party to perform his 1998 single Outside, whose lyrics are centred on a proud reclamation of his widely publicised experience of being arrested in a public bathroom in Los Angeles for engaging in a “lewd act”.

After his tour commitments ended with a stadium gig in Melbourne, Michael stayed in Australia for a couple of months, regularly following Stereogamous to wherever they happened to be DJing each week. Surprised punters would inevitably do a double take: is that really George Michael at a warehouse in Marrickville, dancing shirtless right in front of the booth? The star was happy to hug and dance with anyone who was up for it, so long as they kept their phones and cameras in their pockets.

In the years that followed, the trio partied together in Sydney and London. In 2012, Michael released a Stereogamous remix of his single White Light, and they had begun secretly working on music together before his life was tragically cut short on Christmas Day 2016, aged 53, from what a British coroner would later confirm to be heart and liver disease.

“In his last years, he had a beautiful quality of life,” Seymour tells Review. “He didn’t die looking back at his glory days; he was loving life more than he ever had. And so when it came to him passing, we wanted to honour our brother and our dear friend, who was a saint and an asset to our community.”

Within a week of Michael’s sudden demise, street artist Scott Marsh had painted the colourful memorial, having previously been contacted by Mac — a longtime admirer of his murals — on Facebook with the rare and desirable offer of a large, clean wall facing a rail corridor.

“When George passed away, they really wanted to paint something for him,” Marsh says. “We sat down, had a couple of beers and a chat about it, and came up with the concept of him as ‘the patron saint of the gays’.”

More than just a symbol of a widely beloved performer known for solo hits such as Faith, Freedom! ’90 and Fastlove, the mural became a social object, while its adjoining park became a lightning rod for community and a new local landmark, all thanks to Michael’s saintly visage.

“It always made me smile, and it made other people smile as well,” says Mac. “It was a daily thing of joy, every time. You never got tired of it; it was something beautiful, just existing, but everyone could share it.”

Seymour observed an even deeper connection. “From the moment it went up, this park became a queer sacred space,” he says.

“People came and left flowers. People came with their little Bluetooth speakers and played George Michael, and threw down a picnic rug and had a wine. Gay people, we don’t have churches or synagogues or RSL clubs or anything like that. We have our discotheques, but there’s no spaces for us to come and grieve, and be, and have what I guess you could call a spiritual moment. This mural gave people the opportunity to do that.”

For 11 months, Marsh’s artwork stood loud, proud and unmolested. But as the end of 2017 approached, and as soon as the affirmative result of the national postal survey on same-sex marriage was announced on November 15, the image of peace and love began to attract individuals convinced St George represented the precise opposite intent.

The mural was attacked seven times in the space of three days by different individuals and groups attempting to paint over it. Thugs in cars yelled homophobic taunts and threatened arson; each morning, a box of matches was left on their doorstop.

Mac and Seymour responded by marshaling their neighbourhood and wider queer community as best they could, including a 100-strong beers-and-pizza vigil in the park on a Friday night through to 4am the following day. But the tide of love could not hold back the hate indefinitely. While the housemates were at a nearby police station making a statement about the attempted vandalism they had witnessed, the final attacker came armed with blackout paint, a roller and criminal intent.

This time the blow was fatal and permanent: by the time they returned home, the mural had been covered in thick black paint that obscured most of St George’s upper body and face. All that remained was his forehead, his perfect hair and his left eye peeking out from behind an ugly, immovable stain.

-

On the other side of the mural, Mac and Seymour were emotionally battered and bruised by what had transpired in those few days since the yes vote on same-sex marriage had succeeded. What began as a celebration of their friend and a gay icon became a battleground for an extremist ideology and an arm wrestle between tolerance and intolerance. That sense of joy that the mural had once invoked had been extinguished.

“Every time I walked out of the house, I was angry, upset, depressed, for a long time,” says Mac. “And then it was also: what do we do with it? Do we paint over it? There was a period there where it was like, ‘F..k it — we leave it and it’s a reminder of the hatred that’s been displayed, and the aggression and the irrationality.’

“But then that became cancerous in itself. People had written beautiful messages in chalk, and that was gorgeous — and then it would rain and that would go, and it was still there as this ugly reminder.”

As the months passed, Stereogamous continued working and playing, together and apart, and eventually, a playwright named Lachlan Philpott carefully and tactfully asked Mac whether he’d be up for trying to adapt the story of the mural into something that might work on the page, and then on a stage.

What Philpott was really asking Mac was whether attempting to create art about what had happened on the other side of the wall might help him heal. And so the kernel of an idea was born, which in time would become a stage production centred on a song cycle performed by a community choir. It was to be a celebration of love over hate — of pride over bigotry — named The Rise and Fall of Saint George.

In recent years, Marsh’s bright and provocative illustrations of public figures — Tony Abbott, Kanye West, Alan Jones, Israel Folau, Annastacia Palaszczuk and George Pell among them — had attracted plenty of eyeballs online and in situ.

A satirist at heart, his work attacks politicians and celebrities by skewering them with their own words in a new context. His work has been controversial but the response to his tribute to Michael was intense.

“It’s a huge spin-out,” says Marsh, who prefers covering his face for Review’s photo shoot owing to his background in illegal graffiti. “I paint a lot of murals and they’re almost like a flash in the pan — and then some have a real tangible impact on people, like this one and the Merry Crisis one [of Scott Morrison] that I painted in the bushfires [in 2019]. It’s motivating; it makes you feel like you’re doing the right thing.”

Soon after St George went up, Marsh began receiving requests to print the design on T-shirts. Within days the artist was inundated with hundreds of orders to his online store; he has since sold more than 1000 shirts and mailed them to most of the world’s English-speaking countries, while also donating more than $4000 to Twenty10, a community organisation that provides counselling for LGBTIQA+ youth across NSW.

The young man who blacked out the mural, 24-year-old Ben Gittany — a Christian who claimed he was defending his religion by painting over St George — was later convicted of malicious damage and ordered to carry out 300 hours of community service, as well as pay $14,000 compensation to Mac, the property owner.

“We are not a community where violence, criminal acts and property destruction are sanctioned because you have different beliefs to other people,” NSW Local Court magistrate Carolyn Huntsman said while sentencing Gittany in September 2018. “Every time you have to spend hours washing damaged walls you can reflect on your own conduct.”

Marsh shakes his head at the memory of Gittany’s actions. “It’s the same every time someone paints over a mural: I’m like, ‘You f..king dummies’,” he says with a laugh. “You’re doing the opposite of what you’re setting out to do. If you were smart, you would just let it run its course and let it be.

“I think with this mural — even though it was f..king horrible, everything that happened — it has given birth to this stage production which will have a whole life of its own,” Marsh says.

“It’s amplified the message and it’s reached all over the globe to become this iconic thing, instead of just a mural on a street in Erskineville.”

Late last month, the three friends joined forces once again to create a new work on the side of Mac and Seymour’s home, this time after going through a council approval process.

Now, Marsh’s tribute to Michael sees the singer sitting high on the wall astride a unicorn and raising a peace sign, while underneath him, an intentionally blackened space invites chalk contributions from fans and supporters.

With music written by Mac and lyrics written by Philpott, The Rise and Fall of Saint George had its work-in-progress debut during Sydney Mardi Gras in February 2019, followed by two appearances at Melbourne’s Hamer Hall for Midsumma Festival in January last year.

Under director Kate Champion, the revised show will return to its home town for Sydney Festival, with several new songs and a new finale, while Philpott and his partner will be among the performers in the choir.

Mac’s hope is that the work eventually can travel, to be taken up by community choirs in different cities, so that this unique story of love overcoming hate can find new audiences elsewhere.

Despite the storm clouds that gathered above the exposed wall of their home towards the end of 2017, the housemates were touched by an unexpected shaft of light which appeared during one of those late-night vigils undertaken by neighbours and allies who had gathered in the park near St George in the days before his white robes were blacked out.

A pregnant dog owned by a mutual friend worked its way through the crowd of people sitting around on picnic rugs. When she nestled between Mac and Seymour and rolled on to her back, exposing her engorged teats and bulging belly, the symbolism and symmetry of the moment was too great to ignore.

Having recently lost a great friend, they decided it was time to get a new one. Today, whenever the housemates call out for their pet — a staffy-french bulldog cross — they are met with the adorable face of a creature that reminds them of somebody who filled their lives with light and laughter. His name, of course, is George Michael.

The Rise and Fall of Saint George will be performed on January 15 at Barangaroo Headland, and also live-streamed for free on the Sydney Festival website from 8.30pm AEDT.