Facing the facts of Renaissance portraiture

RENAISSANCE portraiture is the subject of what is clearly one of the great international exhibitions of the past couple of years.

THE portrait, as visitors to the National Gallery of Australia's Renaissance exhibition will have seen, was among the most prominent subjects of modern art, second only in importance to devotional and narrative painting.

The ability to produce likenesses in painting or sculpture, lost for a thousand years after the fall of the Roman Empire, was one of the aspects of ancient art that most fascinated the early modern period, and the result was a spate of effigies in every possible medium and a comprehensive gallery of most of the important individuals of the period.

Renaissance portraiture is the subject of what is clearly one of the great international exhibitions of the past couple of years, and one that I am particularly sorry not to be able to able to review properly in these pages: The Renaissance Portrait: from Donatello to Bellini, which originated at the Bode Museum in Berlin and has recently opened at the Metropolitan Museum in New York. Fortunately, the show is accompanied by an outstanding catalogue, whose scholarly and often brilliant essays and individual entries establish it as a new reference work.

One of the questions explored in this exhibition is the relation between likeness and ideal image: the front and back covers of the catalogue, indeed, implicitly contrast Dominico Ghirlandaio's naturalistic rendering of an old man and a boy with Botticelli's ideal portrait of a young woman, traditionally identified as Simonetta Vespucci, that was the centrepiece of the Botticelli exhibition in Frankfurt reviewed here almost exactly two years ago.

Portrait painters have always had to deal with the twin demands of patrons for striking likeness and as much flattery as can be accommodated without implausibility, but Renaissance conceptions of the ideal, with their literary and philosophical roots, go much deeper than personal vanity.

Another is the matter of connoisseurship briefly mentioned here a fortnight ago, as well as related problems of the practice and even ethics of restoration. In the course of the 19th century rediscovery of the period and the identification and attribution of countless half-forgotten works, as one contributor points out, "the marketplace and the museums generated a history of Renaissance portraiture that was largely one of great artists and, wherever possible, celebrated sitters". This was motivated in large part by the need to sell familiar names to the immensely rich Americans who were the greatest collectors of art a century ago.

Of course, the search for celebrated sitters is not entirely unjustified, considering the period's fascination with portraiture and the likelihood that the great would be commemorated in paintings, sculptures or medals. But not everyone who was wealthy or important or interesting at the time remains famous today, and one always has to be at least sceptical when a previously obscure portrait is suddenly identified with the most famous or notorious names.

Such was the case with a portrait at the NGV which the gallery declared in 2009 to be the work of Dosso Dossi and a portrait of Lucrezia Borgia; as I observed in these pages at the time, the attribution to Dossi is credible, but the identification of the sitter is less convincing.

Both sets of questions are relevant to the other outstanding Renaissance exhibition -- and one which I was fortunate to see in London a few weeks ago -- the National Gallery's Leonardo da Vinci: painter at the court of Milan. The show runs for a few more weeks but is exceedingly hard to get into: all online tickets are booked out, and queues form from very early to obtain the limited number of tickets for sale on each day. Once again, however, there is a very fine catalogue which testifies to the depth of research that goes into a great exhibition; this too will remain an important reference work.

As the London exhibition's subtitle makes clear, its focus is on Leonardo's time at the court of the Sforzas in Milan from around 1482 to 1499, the years of his maturity and also those in which he executed most of his painted oeuvre; the emphasis of the show, indeed, is on his work as a painter, leaving aside the question of his scientific research except where it inevitably appears in his study of anatomy.

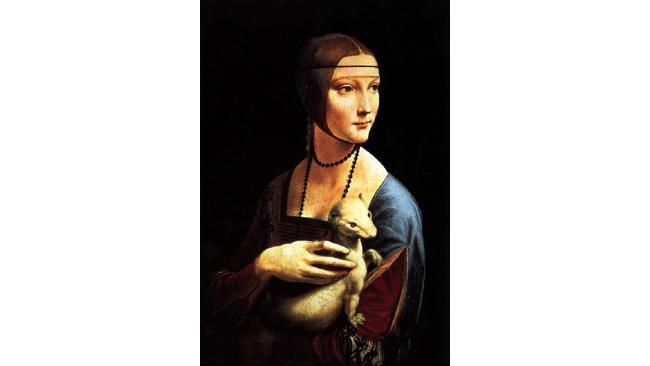

It is quite literally a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to see most of the masterpieces of this period assembled in a few rooms, and in particular the first time the two versions of the Virgin of the Rocks have ever been shown together. It is also an opportunity to consider Leonardo's achievement in portraiture; most beautiful is the Lady with an ermine, the portrait of Ludovico Sforza's mistress Cecilia Gallerani, from the National Museum in Cracow.

This extraordinary painting is reproduced on the cover of the catalogue, fortuitously as it does in fact represent a synthesis of the two poles of earlier portraiture represented on the front and back of the other catalogue. Cecilia is both vividly, almost miraculously, real and an ideal representation of inner and outer harmony.

What prevents Leonardo's ideal from being disembodied and remote is his understanding of movement. For all her poise, Cecilia turns her head in quite pronounced contrapposto to the axis of her torso -- in fact as far as the head can comfortably turn: Alberti, whose writings Leonardo knew, had observed that the head cannot turn further than alignment with the shoulder. At the same time her excessively refined fingers lightly but decisively clutch the white ermine by his shoulder girdle, while the animal too turns his head and pushes down against her elbow with his muscular right leg.

Vasari recognised that Leonardo was the founder of the terza maniera of Renaissance painting, in effect what we call the High Renaissance. But the heart of his innovation was the mastery of movement and the new dynamic unity this gave both to single figures and to groups within a composition. We can see this in a number of drawings, both sketches from life in which the artist captures -- as he recommends in his notes -- attitudes and gestures seen in real life, and invention studies, in which we can always see the priority given to the connection of the parts of the body within a common movement.

This is also, of course, the reason for his profound interest in anatomy, in which field his scientific contribution must also be acknowledged as decisive. The structure of the body had been comprehensively described by Galen in the second century, but no useful illustrations had survived from antiquity. The earliest printed anatomical illustrations in Leonardo's own lifetime were highly schematic, like those in the Fascicolo di medicina (Venice, 1495). Leonardo dissected bodies and made anatomical drawings of a literally unprecedented quality, the direct forerunners of the great illustrations of Vesalius in De humani corporis fabrica (1543). No wonder he insisted at length in his notebooks on the superiority of drawing over writing as a tool of scientific knowledge.

The clearest illustration of Leonardo's love of movement, however, is his unfinished St Jerome from the Vatican. Here we see the saint, the translator of the Bible from Hebrew and Greek into Latin, in meditation and self-mortification, about to strike himself with the stone he holds in his right hand.

The subject is common, but where earlier artists often represent the action as originating from the elbow, Leonardo describes a great swinging motion which involves the whole body, from head to torso and all four limbs. Movement becomes the secret of dynamic unity.

The most remarkable instance of dynamic unity in a group is the Madonna and child with St Anne. The show includes not only the National Gallery's own cartoon but the extraordinary little sketch from the British Museum in which we can see the artist drawing and redrawing the figures in quest of their perfect and inevitable conjunction. A similar concern for movement in groups is visible, but in a less evolved form, in the earlier Madonna of the Rocks, and some of the changes in the second version, here argued plausibly as an autograph work, are in the interests of a greater formal unity.

Movement was also the basis of his compositional solution to the problem of the Last Supper, an unpromising subject that involves 13 figures lined up behind a table (or 12 if one followed the traditional solution of isolating Judas on the other side of the table).

Leonardo placed Christ in the centre, forming a still triangular form with its own internal but resolved movement, while his announcement that one of the disciples will betray him provokes waves of commotion through the group, which breaks into four groups of three men each.

The Last Supper, one of the artist's most important works in Milan, cannot of course leave the wall of the refectory on which it was painted, but is represented here both by a minute reproduction of the tragically damaged original and by an equally accurate version of a copy made soon after completion by his pupil Giampietrino, that allows us to see many details irreparably lost in the original.

In this ambitious history painting, more obviously than in other works in the exhibition, Leonardo is concerned with what were often called the affetti and later the passions -- the inner life or emotions of the characters represented. In a passage in his notebooks, he observes that the artist has to represent two things: the body of man and the emotions in his mind (and indeed elsewhere he advises the artist to study the actions of the mute, who are obliged to communicate their feelings without the use of words). Significantly, motions and emotions are connoted by the same word (moti) so that there is a direct connection between the movements of the mind and those of the body.

It is important, considering Leonardo's interests in areas that can be broadly considered as scientific, to emphasise that he does not think at all in the mechanistic way characteristic of 17th-century thinkers such as Descartes. The relation between the moti of the mind and those of the body is not, therefore, one of cause and effect as it is for a post-cartesian artist such as Charles Le Brun, but one of direct analogy. It is this same analogical thinking that allows him, in some of his most mysterious drawings, to perceive a real affinity between the forms and patterns of hair and those of water or -- here in the drawing of a youth in profile -- of plants; at the deepest level, movement is a clue to the pattern of life itself.

Leonardo da Vinci: painter at the court of Milan

National Gallery of London: to February 5

The Renaissance Portrait from Donatello to Bellini

Metropolitan Museum, New York: to March 18