Fabric of a rich cultural life

The title of this exhibition evokes both the journeys of the collector and those of civilisations as they spread and migrate across the world, transforming the lives and the spiritual universes of the peoples with whom they come in contact.

The title of this exhibition evokes both the journeys of the collector and those of civilisations as they spread and migrate across the world, transforming the lives and the spiritual universes of the peoples with whom they come in contact. At the same time the metaphor of weaving recalls the textiles which are so prominent a part of this story and which, like ceramics, are among the earliest crafts of civilised peoples.

The travels of Michael Abbott which began in Indonesia in the 1960s led to the formation of a unique collection, or perhaps one should say series of collections that like Lindsay’s magic pudding have been divided and generously gifted over the decades to many museums around Australia, in addition to the Art Gallery of South Australia, with which Abbott is most closely associated.

Abbott is indeed a model of the kind of private collector who makes a truly valuable contribution to the cultural life of a nation, because of the passion and expertise he has brought to understanding and acquiring cultural artefacts that are beautiful, significant and little-known to non-specialists. We have had book collectors in Australia who have made important donations and bequests to libraries, and there have been art collectors, too, from Howard Hinton to James Fairfax.

Contemporary art collectors and corporate collections could similarly play a useful role if they concentrated on artists, genres, or styles that were not already fashionable; unfortunately most of them buy from the same approved shopping list as all the public galleries, who would rather be wrong together than right alone. As for those who collect for investment, they are even more likely to follow the current of fashion.

Abbott’s collecting was motivated by a singular aesthetic sense combined with a fascination for the culture and histories of South-East Asia. From a very early age he had an excellent eye; he supplemented this natural ability with wide reading, and eventually with personal connections with other collectors and scholars all over the world. These friendships and relationships are reflected in the beautiful book that has been produced on the occasion of the exhibition, although it is a survey of the Abbott collection and a gathering of scholarly essays on the various questions it raises, rather than a catalogue of the present exhibition.

It is interesting to note that the particular field of trade textiles that Abbott chose to study had not been deeply studied when he first took an interest in it, and it was commonly thought that no textiles found in Indonesia could be older than a century or so. The appearance of the trade stamp “VOC”, the initials of the Dutch East India Company, which was dissolved in 1799, immediately demonstrated that many pieces belonged to the 18th century or possibly even earlier. The cover of the book reproduces a textile which subsequent carbon-dating has shown to be as old as the late 14th or early 15th century.

Abbott’s collection and his gifts to the Art Gallery of South Australia have been the focus of several exhibitions I have visited over the years; this one includes groups of works reflecting the rich and constant interchange of cultural influences, technologies and goods across the South-East Asian region and the Indonesian archipelago. From our point of view in Australia, it is striking that none of these networks reached our continent, which was perhaps simply too remote and was to remain in a kind of cultural stasis until the sudden arrival of the modern world and one could say of history itself less than a quarter of a millennium ago.

All over South-East Asia, in contrast, early animistic and tribal societies were transformed by the two civilisations of China and especially India to their north and northwest, and later by the Islamic world further west. Cambodia, for example, became a magnificent centre of Hindu civilisation before turning to Buddhism, and Java too has wonderful monuments of both Hinduism at Prambanan, and Buddhism at Borobudur, both of the 9th century AD, before Islam became the dominant religion from the 14th century onwards, leaving Bali as an outpost of Hinduism.

The first room of the exhibition has several funerary artefacts which testify to the persistence of animistic beliefs, as in many cultures, alongside the more sophisticated religious systems. One of the most remarkable objects here is an elaborately carved aristocratic coffin, or erong, from South Sulawesi. These fine wooden sarcophaguses were evidently neither burned nor buried, but treated as a kind of house for the deceased; radiocarbon dating has established that it was made in the 16th century and is in fact the oldest known example of such a coffin.

Nearby are much more recent pieces such as a remarkable ancestral portrait, or tau-tau, made in 1979 to commemorate an aristocrat who had died three years earlier. The figure, whose making involved two animal sacrifices, as the label inform us, is dressed in traditional clothes and wears an Indian heirloom textile as a sash. Another remarkable wooden figure, also elaborately clothed, stands on one end of a coffin; but this is a funerary puppet, designed to provide ritual entertainment at the funeral of a childless man. The figure has movable limbs and even, intriguingly, a tongue and penis, all of which could be operated by a system of pulleys as the figure danced for the dead man.

Nearby, in contrast, are several fine ceramic vessels from China – once again attesting to the reach of trade routes – at least one of which is over a thousand years old, while another is about 800 years old and others more recent.

Other pieces are from Indochina or made by immigrant peoples from the Philippines. The reason they are so old is that they were highly valued, perhaps especially in pre-ceramic tribal communities. One is recorded as having been given as a gift to a Dayak chief in East Kalimantan to celebrate his conversion to Islam.

Among all these artefacts are a couple of books, a Koran and another sacred text, written in Arabic and annotated in the margins. Literacy had come to Indonesia much earlier, with Hindu and Buddhist texts in Sanskrit and Pali – starting from about the 3rd century AD and becoming more widespread from the 7th century – but now this was a new religion with a sacred text that could not be translated into any other tongue, and indeed even after the invention of printing could only be reproduced by lithograph.

No doubt too the Islamic scriptures, because of a different kind of proselytising, penetrated many parts of the archipelago that literacy had not previously reached, and one can only imagine the fascination of the illiterate tribal peoples with these pages of incomprehensible signs which were said to be God’s holy word. Unlike in other parts of the Islamic world, Arabic never superseded native languages in daily use, but the very writing acquired a kind of mystical authority; as we see here, ceramic dishes could be decorated in China with Koranic verses for Islamic markets, and eventually even factories in England produced export wares with Arabic inscriptions.

There are many other fascinating things in this exhibition, including a set of material from Bali. A printed cloth from India, traded by the VOC for spices in the 18th century, represents the climactic battle between Rama, assisted by the monkey-god Hanuman, and the demon Ravana, from the Sanskrit epic Ramayana. As anyone who has spent time in Indonesia will know, this is still one of the most popular stories in mask and puppet theatre, even in Islamic Java, where all the classic dance and drama remains Hindu in inspiration.

One of the most interesting and probably least familiar parts of the exhibition concerns the Indian religion of Jainism. Even those who have some idea of the history and tenets of Hinduism – whose origins are literally lost in antiquity and which is often considered the oldest religion in the world – and Buddhism, which arose in the 6th century BC, may have a very shaky idea of the origins and chronology of Jainism. And this is not surprising, since Jain tradition rather unhelpfully claims a history of millions of years.

More plausibly, Jainism is clearly one of the many creeds that arose out of the immensely fertile religious culture of early India, which itself goes back to the arrival of the Indo-Aryans in India around the time of Mycenaean civilisation in Greece, in the mid-second millennium BC.

When exactly Jainism emerged as a distinct system is hard to say, although it clearly has some affinities with Buddhism, even in its iconography. Thus the 12th-century black stone carving of the 19th Jina Malli in this exhibition, could be mistaken for a Buddha in meditation until we realise that it is lacking several iconographical attributes, and is naked like all Jina figures and unlike any figures of Buddha.

The nakedness of Jain monks and sacred figures represents the ultimate expression of their central doctrine of non-attachment – a theme that is also familiar from Buddhist doctrine and even from Krishna’s teaching of acting without attachment in the Bhagavad Gita. Asceticism, radical non-violence and the pursuit of absolute knowledge or omniscience are all part of achieving liberation from the cycle of reincarnation (again a theme shared with Buddhism and some currents of Hinduism).

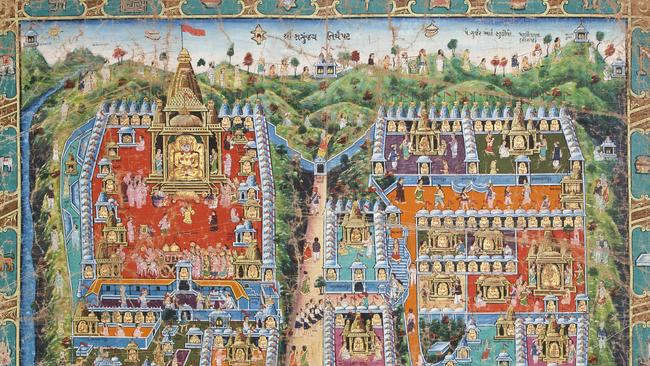

The theme of knowledge appears here in the curious “game of knowledge” which looks oddly familiar, because it is in fact the origin of our game of Snakes and Ladders. Pilgrimage to sites associated with holy men and teachers is also important. A painting on cloth from 1957 depicts a pilgrimage to the Satrunjaya temple in Gujarat, a particularly holy place because it was said to have been on this hill that the first Jina delivered his first sermon. The painting offers a schematic view of the sacred hill, combining aerial and frontal views, but no doubt accurately representing the various parts of the site, as pilgrims ascend from the realistic modern cars on the road in the foreground, through the wood on the lower slopes of the hill and then up a main road between two main parts of the temple complex.

Most intriguing, perhaps, are several diagrammatic figures that are meant as a kind of symbolic summation of teaching, including the Auspicious drawing of Ganesha (c. 1725-1825), which represents the elephant-headed son of Shiva as encompassing the universe, and a couple other images which represent to the universe in the form of a human body. These are not, apparently, meant to allude to a microcosm-macrocosm theory so much as to serve as a kind of mnemonic, while in a painting on paper (c. 1775-1800), there is also a series of seven images of a man, no doubt intended to represent the successive steps to enlightenment.

.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout