Did Harry Houdini really disturb a body in the Yarra River?

Alan Attwood examines some of the stranger claims made by Harry Houdini during his tour of Victoria in 1910.

There was no eureka moment. No sudden revelation causing me to sit upright in bed in the early hours thinking: “That’s it …” Nothing that might make an arresting scene in a movie or a Pre-Raphaelite-style painting with the title When Inspiration Strikes.

I can’t even say for sure when I decided to write a book about Harry Houdini. For I’ve had Harry in my head for well over 20 years. And not so much Houdini the escape artist, the man whose name is still appropriated when anyone, anywhere, squeaks out of a tight spot. My interest initially was in Houdini the aviator, the Hungarian-born American whose name is often cited as the first to make a powered, controlled flight in Australia – in Diggers Rest, outside Melbourne, in February 1910.

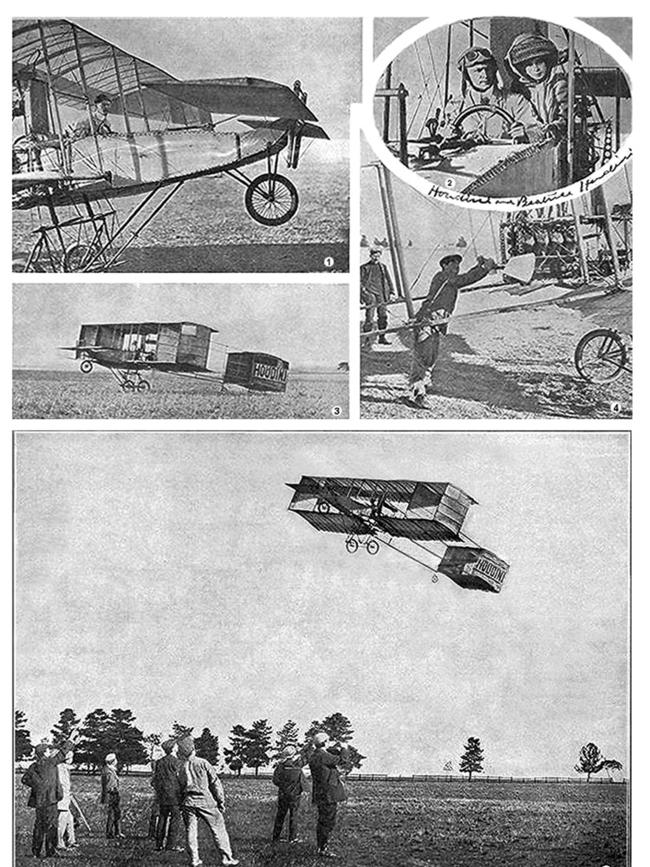

Houdini, then 35, was convinced that his feats as an aviator would be remembered long after his escapes and stunts were forgotten. He was wrong about that. Indeed, after some exhibition flights in Sydney following his Melbourne season, he sold his rickety biplane and never flew again. Debate still bubbles among Australian aviation buffs about his claim to the record: others had got off the ground before him but didn’t have his knack for publicity.

It’s not much of a record anyway: the Wright brothers had been airborne in the US more than six years earlier and in June 1909 Frenchman Louis Bleriot won a £1000 prize put up by a London newspaper by flying clear across the English Channel. Bleriot’s flight lasted 36 minutes and 30 seconds; Houdini’s longest ascent over Diggers Rest lasted less than eight minutes and didn’t get him anywhere much except above and around a paddock.

Yet I was intrigued. Houdini a pilot: who knew? And what was he doing here? I started poring over newspapers and magazines from 1910, when Houdini’s name didn’t have its modern resonance. He was just another showman, competing against the likes of the Brothers Martine, trampoline acrobats; Fred Curran, the “Quaint Comedian”; and the latest threat to live performers – moving pictures. WC Fields, who later became a film star, had already performed in Australia as a comedy juggler.

But Houdini had a formidable ally: a one-time English vaudeville performer calling himself Harry Rickards, noted for his rollicking rendition of the song Captain Jinks of the Horse Marines, who had migrated in the late 19th century and reinvented himself as a theatrical impresario: the Harry M. Miller of his time. Rickards, who billed himself Sole Proprietor and Manager of Melbourne’s Opera House (in Sydney he had the Tivoli Theatre), was responsible for the breathless, multi-decked ads in newspaper Amusements columns:

“FIRST APPEARANCE IN AUSTRALIA … A MAMMOTH ATTRACTION … Undoubtedly the Greatest and Most Sensational Act that has ever been Engaged for Australia by any Manager … HOUDINI, The Great Mysteriarch.”

Houdini himself – the creation of Ehrich Weiss, son of a rabbi – would have expected no less. He understood the importance of marketing. He would have been all over social media today, Tik-Tokking relentlessly. In 1910 his standard attention-seeking trick was a leap in chains from a bridge or (as happened in Sydney) a diving tower.

The Melbourne jump, advertised in advance by urchins paid to carry billboards around town, became part of his legend. He claimed to have disturbed a body in the Yarra River. Later, he described a close encounter with a shark. When you check the papers from that time, however, the leap is described in detail. But there’s no mention of a corpse. And nothing to file under J for Jaws.

Houdini was a storyteller whose favourite subject was himself. Truth was an optional extra. He hovers in that murky no-man’s-land between fact and fiction. And as I scanned those old papers – one of which I would work for 68 years later – I became intrigued by other things going on: a motor-car driver charged with excessive speed (27 miles per hour); JC Williamson, one of Rickards’ rivals, trumpeting the Australian premiere of Puccini’s opera Madame Butterfly six years after its Milan opening; the impending arrival of Halley’s comet, which caused both fascination and fear (there was talk of noxious gases in its tail). There were ads for gramophones; mentions of Melba and Caruso.

When I read the list of signatories to witness statements for Houdini’s flights – including Ralph C. Banks, Melbourne Motor Garage (another aviator); JH Jordan, Ascot Vale (Houdini’s driver); and, most intriguingly, A. Bindo Serani, “Consul for the Italian Touring Club” – I realised I was assembling a cast of characters. More wandered on stage when I gazed at contemporary photographs.

I didn’t find any in which Houdini’s mechanic Brassac, a Frenchman who had helped get Bleriot over the Channel, was not wearing a hat. Houdini once said of Brassac: “No mother could tend her child more tenderly than Brassac does my machine.” Studying the inscription on an ugly trophy presented to him by the Aerial League of Australia it occurred to me that Houdini’s claim to be first could well rest on some sleight of hand, if not an outright fib.

And I fell a little in love with Houdini’s long-suffering wife, Bess, stuck in hotel rooms around the world while her husband jumped off bridges or shimmied out of straitjackets and fretted about his absent mother, the formidable Cecilia. A smile often seems to be hovering around Bess’s lips in photographs, as if she had some secrets of her own. It was time to share some of them.

Research is seductive. Writing is harder. This Houdini book went through many, many drafts. It grew smaller rather than bigger, which is usually a good thing. Characters who had made entrances and even stolen a scene or two vanished altogether. Others got their own voices. I took as many wrong turns as the visiting escapologist himself on his uncomfortable way out to Diggers Rest – where there is now a Houdini Drive and (ironically) planes rumble overhead from the nearby airport.

Poor Harry got stuck in a desk drawer from which he couldn’t escape. Covid helped get him out. He became a lockdown project. And slowly I started to understand what the book is about: music and magic and flying machines; a story about a storyteller. Fiction or nonfiction? Impossible to say. For Houdini was a master of illusion, a showman who made people believe that what they had seen was real.

Besides, as I have someone say, all the most unbelievable stories are true.

Houdini Unbound,published by Melbourne Books, is out in May. Alan Attwood’s previous novel, Burke’s Soldier (Viking, 2003), was about John King, a largely forgotten figure from the Burke and Wills expedition in the 1860s.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout