Cressida Campbell: truth, heart, skill and a rare artistry

Cressida Campbell’s exhibition at the National Gallery of Australia reveals an artist at the very top of her game

Cressida Campbell’s Nasturtiums (2002) presents us with the image, one might almost say the vision, of three Chinese blue-and-white bowls on a tabletop covered with an oriental textile, perhaps South-East Asian. The bowls are half-filled with water, and in the water float sprigs of nasturtiums, with their bright yellow and orange blossoms and their soft blue-green veined leaves in the clear sunlight.

The flowers are vividly alive in their fragile and ephemeral beauty, the leaves and tender stalks full of the vitality of things only just picked. The picture offers one of the greatest delights of art, the sense of a fragment of life captured and preserved: not so much the visual appearance of the flowers as the way we feel and experience them; something that could not be conveyed in the same way by a botanical illustrator or a photographer.

Our pleasure arises from the apprehension of a mysterious reality that goes beyond, and indeed has little to do with optical illusion. When we look more closely, we begin to realise how much is artificial in this composition: the bowls are seen from above, in a perspective that allows them to fill the frame, with no space beyond them; two of them are cut off by the edges of the picture; each is accompanied by a round disk of shadow.

The artifice goes further: not only are the shadows flat disks, they are divided from the blue of the tabletop by a fine line; all the other areas of colour are also separate and individually flat, like the white rims of the bowls which are rings of white. All of this makes us see the composition as a pattern; and this does not detract from the vivid sense of life, but rather enhances it.

The most damaging of the various fallacies about art that arose last century was that the invention of photography made manual representation of the world obsolete. Even today, few children are taught to draw or paint properly either at school and in art colleges; instead of acquiring an independent capacity to represent and articulate their experience of the world, they are taken through sterile exercises in copying and pastiching the dead styles of the modernist back catalogue.

The idea that photography makes drawing obsolete is as absurd as it would be to suggest that voice recording makes poetry obsolete. Who needs poems to express joy and sadness when you can simply record people laughing or weeping? But of course poetry is not just the “recording” of emotion. As John Donne implied when he explained his reason for writing about his unhappiness in love, “grief brought to numbers could not be so fierce”, poetry is about discipline, order and artifice.

All art is first of all something made, or what in Greek was called “poiesis” – for a poet is a maker – and therefore something essentially and even intentionally different from the order of nature. In the “imitation” of nature or the world of experience therefore, or what Aristotle calls “mimesis”, there is an inherent paradox: mimesis can only be effective through the conversion into poiesis; the sense of reality can only become vivid through artifice. The line of verse can only be moving and memorable because it has rhythm and shape; the picture can only be lifelike because it is also unlike life.

Campbell’s process epitomises this kind of transformation. It is adapted from Japanese woodblock printing, ukiyoe, which flourished from the late 18th to the late 19th centuries, and made a strong impression on such modern artists as Manet, Whistler and the impressionists. In the early 20th century, as discussed recently in my review of Ethel Spowers and Eveline Syme, it was adopted in simplified form using the new medium of linoleum.

In a Japanese woodblock print, the design is initially drawn on paper, then transferred to a block to produce the first, black-and-white impression. Then additional blocks are made for each separate colour, which must all be printed successively in perfect registration. It is a laborious and highly skilled process, especially when we consider that ukiyoe prints were published in large numbers.

When Campbell began to work with prints, she would also produce multiples, but from about 1986 she settled on the formula that she has developed ever since: she works with a single block for all the colours in the image, and makes a single print. But she also exhibits the block, so that each work exists in two forms: as the painted block and as the paper print, which, like all prints, is the reverse of the design on the block.

The National Gallery summer exhibition of Campbell’s work includes a video interview which is both informative and moving. Scenes in which the artist is working and explains her process help the viewer to understand it, especially those for whom printmaking in general is unfamiliar, let alone sophisticated variations on a particular and already complex technique.

After selecting or setting up a motif, Campbell starts by drawing directly onto the block; she also makes colour notes in water colour and gouache for ephemeral elements like flowers – sheets of these are included as examples of her working practice in a display case – and when she is happy with the composition, she incises the outline of her drawing, thus effectively conferring the same level of reality on the bowl, the flowers and even the cast shadows of the bowls. Her pictures are a world in which all phenomena are equally substantial.

In traditional ukiyoe, the whole surface of the block would be cut back except for the area that was meant to print a particular colour; but because all the colours in Campbell’s work are to be printed from the same block, she confines herself to an outline separating and delimiting each area of pigment.

Then the block is painted in water-based colours, both for their particular aesthetic qualities and because they need to be capable of rewetting; the paint is applied quite thickly, since it is meant to print onto a sheet of paper. When the block is finally ready, as we see in the video in the making of a large tondo, the printing can proceed. First a sheet of paper must be moistened, as in other forms of printing, to render it receptive to the pigments. The block is also sprayed with a fine mist of water to re-wet the paint.

Then the paper is gently laid onto the block, and worked with a hand-roller to impress the paint onto the sheet. What I did not understand until seeing Campbell at work in the film is that she then repeatedly and very carefully lifts one side and then the other, re-spraying and re-rolling until a good impression is obtained. Even that is not the end, for both the block and the printed work will be further retouched in water colour and gouache before they are completed. But in spite of subsequent retouching, it is the print technique that gives the work its strong decorative surface and the flatness that forms such a strong aesthetic tension with the illusion of space and perspective.

The exhibition is divided into several sections, covering the various genres to which Campbell has turned her attention. One of the most important in her oeuvre is still life, particularly of flowers and other plants, as we have already seen, and to a lesser extent of fruit and other kinds of food.

Two of the first pictures we encounter are luncheon pieces, and the direct heirs of the golden age of Dutch still life in the 17th century in their depiction of oysters, fish, bread and white wine, eliciting the viewer’s memories of taste and texture. Here too we may be struck, at the very beginning of the exhibition, by the contrast between the sensuous naturalism of colour and the artificiality and stylisation of form.

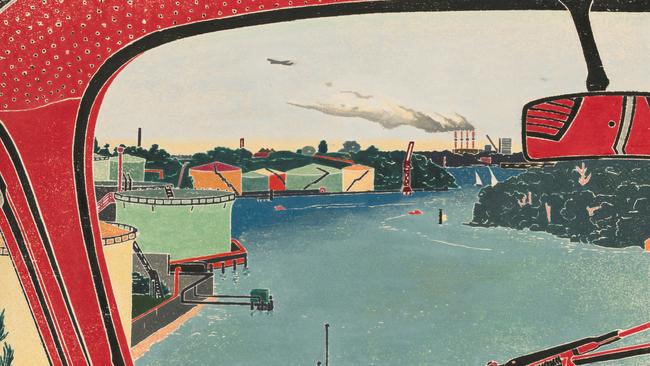

There are some fine landscapes too, but landscape is not really at the heart of Campbell’s inspiration, and the best of them concentrate rather on close-up views of flowers and foliage, or sometimes on dense bushland; in spite of a few harbour panoramas – which in their nature are actually quite flat – she is not really drawn to the depiction of space, or of a world that reaches, as the genre of landscape most fundamentally does, beyond the domain of subjective experience.

Still life is entirely concerned with a reflection on the subjective, but so is one of her most characteristic subjects, the depiction of interiors. There are a couple of memorable interiors of the house of Margaret Olley, who was something of a mentor, and who was herself a great painter of interiors.

The interiors of Campbell’s own house, which she shared for many years with her late husband Peter Crayford until his death in 2011, are particularly poignant. They evoke an eminently civilised, refined, intimate and unpretentious way of life which feels precious and fragile even without reflecting on Crayford’s medical condition and illness.

These interiors seem at first sight straightforward and accessible, but they too exist both as wood block and as reversed print, raising a disturbing ambiguity, as when we remember a place or a painting, but mistake its orientation. Thus in one case in the exhibition, a view of the staircase and back door of the house is shown both as the block and the print; the block preserves the correct orientation, while the print shows us the same scene as though through the looking-glass.

This work, made not long after Crayford’s death, is also charged with feelings of loss and loneliness. The two staircases, going upstairs and down, and door standing ajar, all imply movement in and out of the house, a movement and a presence that are now missing, replaced by the crouching cat who stares at us through the railings; only one of his eyes is visible, a cryptic allusion to bereavement.

In later interiors, Campbell has continued to develop the theme of intimacy – as she observes in the video interview – but also ambiguity and indeed vulnerability. In one work, which I mentioned in reviewing her exhibition in Sydney in 2017, she depicts an interior at night, in which the room is reflected in the windows, while the garden also remains just visible outside. The world of the house is enclosed, yet not watertight; as I observed at the time, her vision is inward but not solipsistic.

On the contrary, keen attentiveness and a sensibility that is equally acute and tender are at the heart of Campbell’s work, as we saw at the beginning with her nasturtiums. But this attentiveness is matched by her consistent devotion to a rigorous and consistent process. As she suggests at the conclusion of the video interview, great work only arises from “truth, heart and skill”.

Story of the Moving Image

Australian Centre for the Moving Image

New permanent exhibition

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout