One of these fallacies is that art is about self-expression. This becomes even more damaging when identity politics lends narcissism and self-pity a veneer of respectability. The truth about self-expression is that our own experience only becomes interesting when we transcend it to discover, through our private joy or suffering, something of universal human interest.

A second fallacy is that art exists to convey messages. Sometimes it is thought of as illustrating overt political ideology, at other times as concerned with the more nebulous yet self-important “concepts”. When even more nebulous, these ideas may be called “notions” – “the notion of desire” used to be a perennial favourite. In most cases the correct term would be either “phenomenon” or “experience”.

This is not to say that art cannot be informed by ideas, even of the most abstract and philosophical nature. The model for such art is Dante’s monumental poetic trilogy, The Divine Comedy, composed almost seven centuries ago (in fact it was completed in 1320, so next year will be the 700th anniversary). The entire work is built on an armature of scholastic philosophy in which the smallest narrative details and the most spontaneous poetic images can fit into a comprehensive allegorical scheme.

And yet Dante’s masterpiece is a poem and not a philosophical treatise because everything in it is so miraculously transmuted into the stuff of imagination and sense-perception that it is moving and memorable even to those who have little or no understanding of its ultimate intellectual infrastructure.

What many, and notably syllabus-writers, fail to understand is the meaning of the aesthetic. This has nothing to do with prettiness. The word comes from the Greek verb aisthanomai, to feel or apprehend by sense-perception. Aesthetic thinking, if we can call it that, is the antithesis of conceptual thinking: the one is based on abstract ideas, the other on sensory, affective and imaginative responses. This distinction is particularly important to ponder in understanding the work of Cornelia Parker, for it looks at first sight like conceptual art, and yet reveals itself ultimately to be deeply instinctual, imaginative and therefore ambiguous rather than in any way programmatic or ideological.

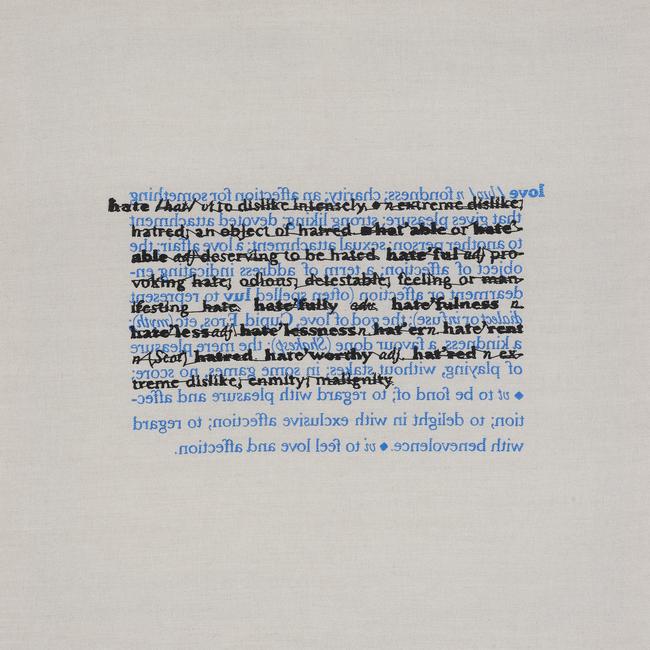

We can see this even in a work that appears quintessentially conceptual, based on dictionary definitions, as in Joseph Kosuth’s One and Three Chairs (1965) and other pieces. But whereas part of Kosuth’s conceit was that the piece could be reproduced with different chairs and different dictionary definitions, Parker has taken all her definitions from the Collins dictionary, which turns out to be vital for her purpose.

For Parker has taken pairs of antonyms from the different parts of the volume where they usually dwell, brought them together and set them up in contest one with the other. And she has done this in the most explicit and concrete way, by literally inscribing one over the other, so that one is written from left to right, in the normal way for European alphabets, and the other from right to left, like Arabic or Persian.

The result is quite fascinating, at its simplest level like a census of the sheer number of words we have to describe or define these important ideas, or their respective importance for us, or the directions of our aspirations. Of course this is not a statistically accurate study and perhaps another dictionary could have yielded slightly different lists; but there is no reason to doubt the general accuracy of the result. Thus it is intriguing to find that the definitions of inside and outside are exactly equal in length. For every thought we have about interiority, in other words, we have a corresponding thought about exteriority. And it is perhaps even more surprising to find that win and lose are almost matching: but the definition of the former is slightly longer, leaving us, in the context of a kind of race, with the feeling that win really is winning.

And, it would seem, it only gets better: pretty is more than twice as long as ugly. Love is longer than hate and right is longer than wrong – this is indeed the first piece we encounter at the beginning of the exhibition. Most impressively of all, light is much longer than dark – just over three times as long in fact. It would be interesting to see if this proportion is similar in other languages, for the human response to light as good and joyful and life-giving and our association of darkness with death and terror seem universal.

And yet for all of these positive results, it is telling that war remains longer than peace. Does this reflect a long-standing dread of war, or a more philosophical recognition, in the manner of Heraclitus, that strife and conflict make the world we live in? Or perhaps, as in Balzac’s famous saying, le bonheur n’a pas d’histoire – literally, there is no story to tell about happiness – and as countless films confirm, there is more to say about the drama of war than the calm routines of peace.

The conceptual point of this work could have been made by setting the definitions side by side, but the idea of running them together, in opposite directions – at war with each other – gave them a concrete and far more memorable imaginative presence. But so did another important element: the fact the definitions were painstakingly embroidered by hand, and the further fact that this embroidery was done by prisoners.

The unusual medium brings with it associations of old-fashioned samplers embroidered with moral or pious sayings, but above all, in an age of copying and pasting text from the web, it turns the process of writing into something slow and contemplative, like the way that medieval monks copied manuscripts as a process of meditation and perhaps sometimes of penance.

Parker used the same process of embroidery for a project to celebrate the 800th anniversary of the Magna Carta in 2015. Concluding that the Wikipedia page condensed most of what she wanted to know about it, but instinctively wanting to counter the information consumerism of the web, she decided to reproduce the whole enormous page in embroidery, doing part of the work herself and having the majority done by volunteers both individually and in institutions.

As these projects already reveal, Parker is closely involved with the social and political life around her, but in an unusual and unexpectedly co-operative manner. She has worked with prisons and other institutions, including parliament – she was commissioned to produce a kind of documentary of the last British general elections in 2017 – and even the army.

In one of her short films she worked with the Royal British Legion at the Poppy Factory in Richmond, which produces all the poppies sold on Remembrance Day to raise money for returned servicemen and their families. The film follows the hypnotically repetitive stamping and cutting of the petals and their assembly and packing – indirectly recalling the process of the mechanical killing of the war – pausing for two minutes silence at 11am on Remembrance Day itself.

As a spinoff of this project she also produced The War Room, a vast space hung like a tent with sheets of the red paper perforated with the tens of thousands of holes from which poppy petals have been cut out, a solemn and melancholy evocation of countless absences. As the installation is fragile and visitors are tempted to touch it, a gallery attendant has offcuts of the red paper that you can handle.

Of the other works in this exhibition one of the most absorbing is Subconscious of a monument, which is composed of thousands of clods of earth removed from underneath the Leaning Tower of Pisa in a successful effort to reverse its slowly but perilously increasing inclination. The construction of the campanile began in the 12th and was completed in the 14th century, so this is earth that has not been disturbed since even before the time of the Magna Carta.

But the dull and almost inaudible historical resonance of the material itself is animated and given meaning by its very precise and indeed exquisitely careful arrangement. The lumps of earth are suspended from the ceiling on fine wires like fishing line, and are all exactly aligned at the top, producing an upper plane that recalls the surface of the ground.

This sense of a ground level is what makes all the other clods feel as though they are underground. But the most remarkable aspect of the installation is the effect of depth that is created, and the way that we are obliged to see each clod in relation to the others behind it.

We don’t normally see the world like this, because our eyes tend to focus on one plane at a time, either close up or plunging into the distance like a telephoto lens, but ignoring the foreground and middleground. Landscape painters have to learn to see all planes projected one onto the other in order to achieve composition: instead of passing from the tree in the foreground to the hills in the background, they see the one projected onto the other, and thus offer us a way to see nature as beautiful, which really means to see beyond the perspective of self-interest.

Something similar happens here, except the multiplicity of suspended clods, all roughly equidistant, forms a baffle that frustrates the eye’s natural tendency to seek out and distinguish planes in space: instead we are forced to see every object behind every other, in something like an image of the amorphousness of being that lies hidden beneath a masterpiece of architectural form.

One of Parker’s most memorable works also suggests amorphousness at first sight: with the help of the army, she had a small shed blown up, then collected all the pieces of the building and its contents, and again painstakingly suspended them from the ceiling. She placed a light in the centre and displayed the whole in a vast darkened room, so the illuminated wreckage casts evocative, slowly moving shadows on the walls.

The destruction of a building seems at first a paradoxical action, for one of the roles of art is to resist the entropy that gradually consumes us and most of our works. But the resulting complex hanging, like a sort of mobile, with its unfamiliar forms and enchanting shadows, shows the destruction was only a prelude to a new creation, one in which an unnoticed and undistinguished utilitarian structure turns into a poetic object that speaks irresistibly to the senses and the imagination.

Cornelia Parker . Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney . Until February 16

There are many misunderstandings about what art is and does, how it is made and what its makers are like, and most of these are entrenched in school syllabuses, with the result that generation after generation learns to repeat the same fallacies.