One consequence was that anxious and pent-up people have spent more time on social media, an environment based on the principle of confirmation bias and the mutual reinforcement of people sharing the same views. The sudden frenzy of statue vandalism around the world was an expression of this overheated human environment, in which passion and rage could be communicated from one person to another as they are in a mob, but in this case without the need for physical proximity.

Social media networks provide an environment in which ideas, and particularly extreme and toxic ones, proliferate by mental contagion in exactly the same way that a disease spreads in an epidemic. The virus metaphor for online transmission has been familiar for many years, but as so often it had become a dead metaphor. This crisis has been an opportunity to reconsider it as very much alive and dangerous.

The same environment has fostered an explosion of conspiracy theories, of which the most familiar was the subject of a Four Corners piece a few weeks ago. A lot of people have convinced themselves that 5G mobile networks are responsible for the current pandemic, or that it is hoax and a pretext for vaccinating the population with microcomputers which will allow them to be controlled by the masters of the digital universe. Those who believe these bizarre ramblings include, disconcertingly, hippies as well as rednecks.

Another growing group of conspiracy believers is the QAnon movement, to whom the BBC recently devoted a short piece. This movement believes in a similar grab-bag of conspiracies, but their core belief seems to be that everything, including the government, the courts, the media and the entertainment industry, is controlled by the so-called deep state, run by Satanist pedophiles, and that President Trump is fighting single-handedly against this monstrous mega-conspiracy against the common people.

The people who were seized with iconoclastic hysteria, and particularly those who wanted to tear down statues of explorers a couple of months ago, have much in common with these conspiracy zealots. For in each case their reactions betray an inability to understand the complexities of the real world and a desperate longing to simplify it into something more manageable.

The underlying reason for current conspiracy theories, or more specifically for the form they take, is clearly that people feel powerless and suspect that they are being manipulated. But they cannot understand the impersonal way that economic and technological forces operate, or the collective nature of social developments, in which they are themselves implicated. It is far easier to imagine that Washington, Wall Street and Silicon Valley are run by a cabal of immensely rich devil-worshipping pedophiles; a ludicrous amalgam, but one conjured out of familiar bogeymen.

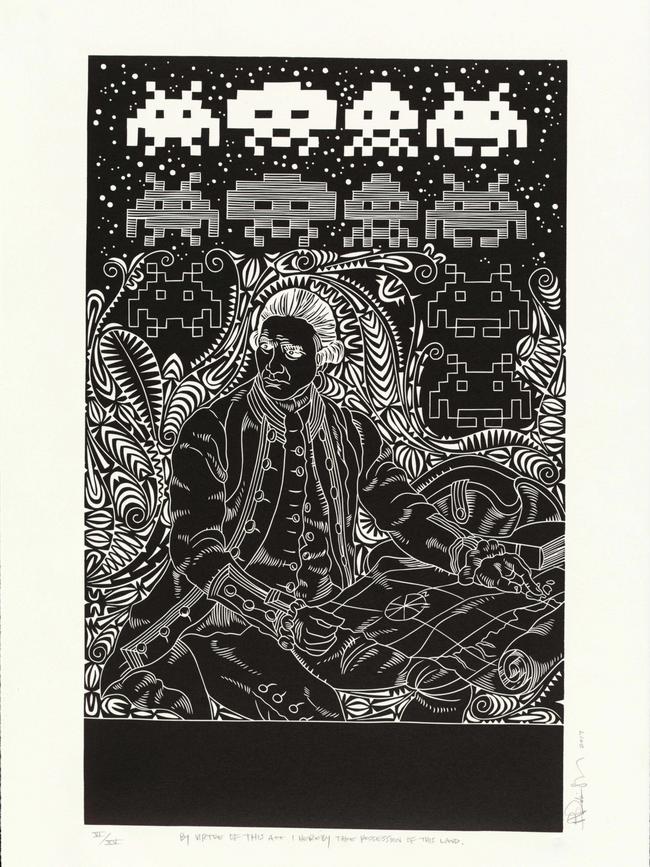

It is just as absurd to blame Columbus or Cook for everything that followed during the centuries of colonisation; not only unfair to the men themselves but a failure of historical imagination and a gross misunderstanding of the long-term historical and cultural factors at play in the periods before and after the lives of these individuals. In the end it is always easier to pin blame on a particular person than to appreciate the powerful but less easily comprehensible currents that drive history.

One of the things most unreasonably held against Cook is that later generations spoke of him carelessly as having discovered Australia. Cook himself would never have dreamt of making such a claim; he and everyone else in his time knew very well that the Dutch had been here over a century and a half earlier and had indeed mapped two-thirds of the continent’s coastline. And much earlier still the existence of a large land mass in our region had been predicted since antiquity — it even had a name, Terra Australis, the southern land, long before European sea-voyages located it on the map of the world.

Cook was a great seafarer, explorer and mapmaker as well as a fine leader of men, whose achievement in relation to Australia’s history was in charting the east coast of the continent and thus at last completing a map that had remained open and unbounded for a century and a half. By an almost poetic coincidence, settlement did not start until some time after the map of the continent was completed, although the more mundane reason for founding a colony was that after the American Revolution the British government could no longer transport convicts to Virginia, Pennsylvania and elsewhere.

The most surprising thing about the settlement of Australia is that it didn’t happen earlier. Even leaving aside other potential settlers from Asia, the Dutch could have founded colonies in several places in the 17th century and that might have provoked rival settlements by Britain and perhaps other European powers. Australia today could be divided into several nations speaking different languages, or be a federation of culturally diverse states like Canada. But the Dutch were not interested because Australia had nothing to offer traders and the inevitable settlement was delayed until the period of Britain’s ascendancy.

But even Cook had no thought of colonies and his voyage had nothing in common with an invasion. He was engaged in a scientific expedition, primarily to observe the Transit of Venus in Tahiti, but he was also carrying Banks and Solander and Parkinson, so the Endeavour was a floating natural history museum. Australia was a treasure-house of new flora and fauna, and the charting of the east coast of the continent was important to determine how far the southern land extended; vast though it is, Australia was not quite as big as had been anticipated, and on subsequent voyages, Cook crisscrossed the South Pacific to rule out the possibility of another southern continent.

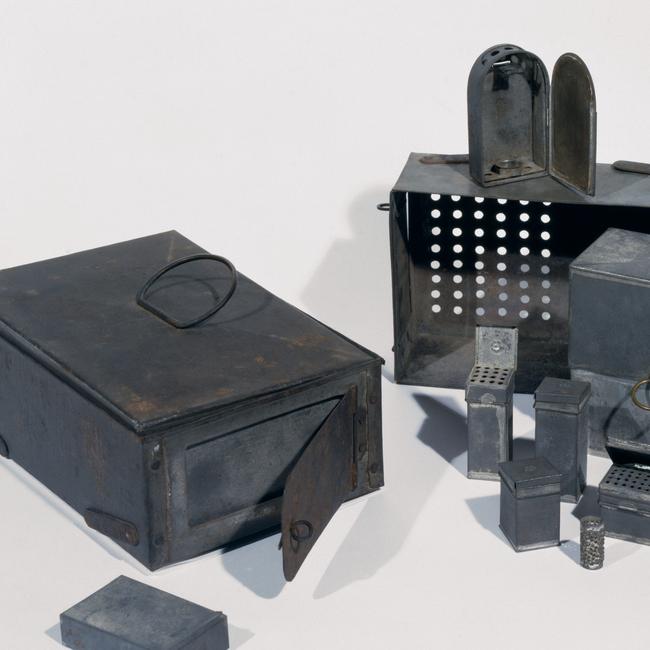

The exhibition follows the path of the Endeavour as she sailed up the east coast from April to August 1770, and there are charts and a model of the ship as well as reconstructions of parts of the ship’s internal environment. Life on board was cramped and hygiene and diet were both matters of concern. Adding sauerkraut to the diet helped prevent scurvy, but the staple was the baked and dried unleavened bread known as ship’s biscuit or colloquially “hard tack”; one pound per man per day was provided by Samuel Pepys’ naval regulations, plus a gallon of beer and ‘other victuals’.

The huge stores of biscuit, which like the French biscuit or the Italian biscotto, simply means “twice cooked” were notoriously prone to infestation by weevils, but as Sir Joseph Banks noted: “We in the cabin however have an easy remedy for this by baking it in an oven, not too hot, which makes them all walk off.”

Another interesting item among Banks’ effects in the exhibition is a little book titled The Oeconomy of Human Life, which is said to have been “translated from an Indian manuscript, written by an ancient Brahmin”. It was originally published in 1751 but was often reprinted and this edition is dated 1762. Over a generation before the foundation of the Asiatic Society in 1784 and the beginning of modern Sanskrit scholarship and comparative linguistics, the Oeconomy is an example of the Enlightenment’s interest in other civilisations, including those of Persia and China, and the critical perspective they could offer on European beliefs and ways of life. The little volume is touchingly inscribed, presumably by Banks: “This book went around the world on the Endeavour.”

The exhibition includes Nathaniel Dance’s impressive portrait of Cook, on loan from Greenwich, as well as a marble bust from the studio of Pajou, an item that I had a small part in helping to identify many years ago. A particular treasure is Cook’s journal in his own hand, open at the page where they first catch sight of the Australian continent on Thursday 19 April 1770: “I have named it Point Hicks because Lieutenant Hicks was the first who discover’d this land.”

There is also the frame that Cook used in mapping the coast, and of course facsimiles of the charts themselves, in which precisely-drawn coastlines and distinctly characterised landmarks such as Mount Dromedary or the Pigeon House form a striking contrast with the generic hills that are used to fill in the vast extent of the unseen interior: the coastline is the narrow track of the known through the endless wastes of the unknown.

The published account of Cook’s voyages is here too — his adventures were as audacious as those of any 20th century astronaut — and after his murder by Hawaiian natives in 1779, Cook became an even more legendary hero, transcending national rivalries and political antagonism. Pajou’s bust was made for a private monument erected for his French admirer, the Marquis Jean-Joseph de Laborde. Marie-Antoinette herself chose to spend the last days before her execution reading this book.

The exhibition goes to great lengths to acknowledge the Aboriginal people whom Cook found already living in the continent, including interviews, tales of encounter orally transmitted, and artefacts. The overall effect is rather confusing and the curators could have been more selective, but clearly they did not want to leave anyone out. Some of these parts of the exhibition are touching, and the most interesting are those that recognise Cook’s conciliatory and humane attitude.

For Cook was in fact the first to write appreciatively about the Aboriginal people, as he noted in his journal for August 23, 1770, at the end of the coastal voyage: “From what I have said of the natives of New Holland, they may appear to be some of the most wretched people upon Earth, but in reality they are far more happier than we Europeans; being wholly unacquainted not only with the superfluous but the necessary conveniences so much sought after in Europe, they are happy in not knowing the use of them […] They live in a tranquillity which is not disturbed by the inequality of condition; the earth and sea of their own accord furnishes them with all things necessary for life.”

In rebutting the assertion that the Aborigines were among the ‘most wretched people upon earth’, Cook was particularly thinking of Dampier’s judgment of them in A New Voyage Around The World (1699). Instead, he proposes a new interpretation inspired by Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s Discours sur les sciences les arts, published in French in 1750 and in English in 1751, in which seemingly primitive peoples may not only be happier than we are but live in a state of harmony with nature that recalls ancient myths of the golden age.

Endeavour Voyage: The Untold Stories of Cook and the First Australians, until April 26, 2021.

The climate of fear engendered by the current pandemic, exacerbated by lockdowns, economic insecurity, social distancing and even the wearing of masks, has inevitably had profound effects on the psychological state of populations around the world. The way that these stresses have manifested themselves, however, was not entirely predictable.