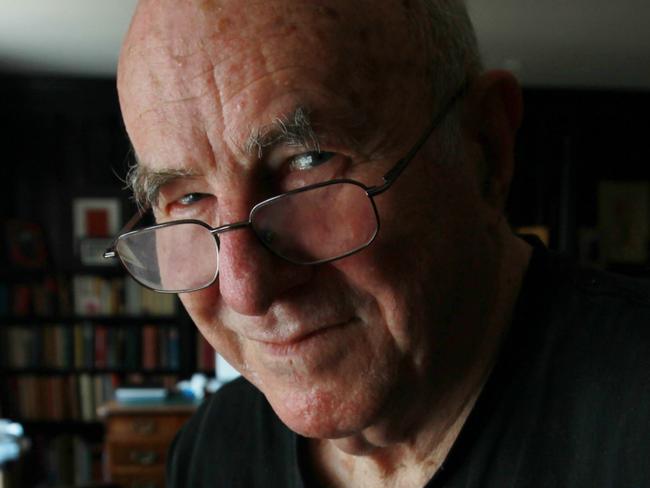

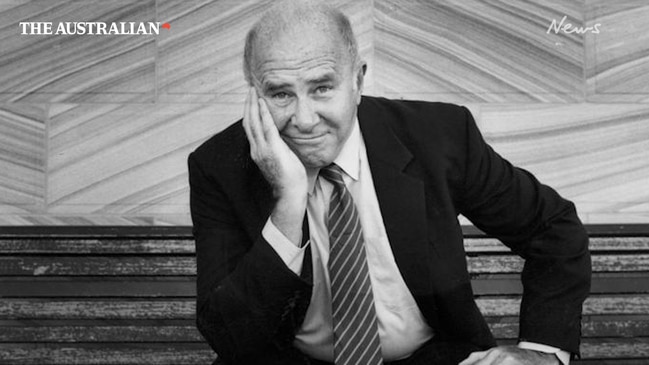

The silencing of a voice like that of Clive James is hard to countenance. He died, with uncharacteristic modesty and decorum (albeit after a number of victory laps on the way out of the oval), several days ago — his agent only releasing news to the effect after a private family funeral on Wednesday.

It is hard because his words, a constellation of them — no, a galaxy’s worth of essays, poems, reviews, memoir, fiction, travelogue and sundry uncategorisable stuff — remain fixed in the Gutenberg firmament. They still glow so vividly, it seems inconceivable that their animating intelligence has definitively blinked out.

Doubtless there are a raft of titles by James still on the publisher’s conveyor belt — and surely, there will rise up a small academic industry on the back of his corpus — but the inimitable phrasing, the nimble arpeggios of wit, the dizzy seesaw between lowbrow and high, are now severed from their source. His death, then, is a matter for sadness tempered by ongoing gratitude.

As a jobbing critic, it is fair to say that this eulogist owed more to James’s example than any other. It was James who forgave my lost years as an undergraduate at the University of Sydney in the early 1990s — dodging lectures on Derrida to read his subversively traditional pieces on poetry and prose in the dim, book-stuffed stacks of Fisher Library.

Afterwards, I would shift venues to the bar of Manning House — where, in fear of Germaine Greer’s sexual overtures, James once reportedly climbed a nearby tree to hide — and immerse myself in his partners in critique, along with shelves worth of formative heroes and heroines: dense, half-graspable works on aesthetics by the Italian philosopher and historian Benedetto Croce; those imperishable memoirs of life under Stalinism by Nadezhda Mandelstam; and the bristling asseverations of critics such as William Empson, Northrop Frye and Edmund Wilson.

When, having dropped out of law, I made my hangdog way to the Woolley Building at Sydney University to beg admittance to a doctorate in English literature (mine was on Byron; James’s on Shelley), it was partly his example that ultimately sent me to the UK for graduate study.

READ MORE: Geordie Williamson — Clive’s lives | Troy Bramston — Clive James’s mini-epic a major flowering of ‘honest, reliable memoirs’ | Trent Dalton — Clive James: life, death and my next great work | Climate alarmists cop a Clive James savaging | Clive James essay — Western climate change alarmists won’t admit they are wrong

Like James, I never completed my doctorate: unlike him, I attended University College in London, rather than Cambridge. After tutorials, I made my way out of the University’s Bloomsbury precinct to Fitzrovia and a pub there called the Pillars of Hercules — a drinking hole so sacred to James’s memory he used it as the title for his second volume of published criticism — to continue the unofficial education he inspired.

Where I departed from James was my decision to return to Australia. For him, the trip to the Old World was a one-way street. Britain was the only location for a person of his talents; it was one of the few cultures of requisite depth and breadth for his mind to sport in. Martin Amis explained to me during an interview a few years ago that, for James, even an England in decline was more interesting than an Australia on the make.

His was a decision that should, however, be considered in its historical context. It was Kenneth Tynan, visiting down under and meeting with the young Robert Hughes, who warned him of the perils of remaining on local ground. If you don’t leave, you’ll end up a village explainer, he said. James also felt this pressure. When he first left for the UK in 1962, the academic infrastructure for Australian literature was still in formation. Our publishing industry was still tied to London’s apron-strings. A sense of national culture was sporadic and halting.

There is a paradox at work here. James and much of his talented generation went offshore because they felt little existed for them at home. Yet their expatriation had an interesting counter-effect.

In Falling Towards England, James recounts wild London parties where then-still-boozing Barry Humphries would gradually achieve horizontality over the course of an evening, emitting a random litany of Aussie colloquialism and advertising jingles with eyes closed on the nearest sofa.

James intuited that, just as James Joyce claimed to have borrowed the English language for his own national purposes in Ulysses, so too was Humphries clearing a space for an antipodean-inflected version of the mother tongue. Humphries made poetry from the linguistic flotsam of his apparently unlovely colonial inheritance. James, likewise, used his brash New World persona to open the field for an emergent Australian sensibility.

While he was often generous to those who remained in Australia — referring to Les Murray, James said that the “best of us” stayed behind — his own cosmopolitan orientation should not blind us to the work he did on behalf of our culture.

Like scholar and critic Frank Kermode, who was based in Sydney for a time during World War II, James revered the best of Australian poetry. He even claimed that, after Spanish language verse, our poetic tradition was the most notable of the 20th century. For one who had already established his bona fides writing brilliantly about Plath and Hughes, Auden and Larkin, such grand claims had real heft.

Viewed in this light, James’s example should put to rest tired old arguments about the relative virtues of those who left and those who stayed. Just as Christina Stead spent her Paris years writing to Clem Christesen, Meanjin’s founding editor back in Melbourne, of Camus and de Beauvoir and Sartre, James’s offshore interests served to collapse cultural distance. Each pole was required for the intellectual current to run.

Of course, having achieved this virtuous end, James managed to alienate many in younger generations who took advantage of the openings he helped create. The crustier edges of his conservatism — particularly his hostility to new iterations of nationalist historiography — have diminished his reputation across the board.

While there is some fairness in this response, there is injustice, too. James’s conservatism also manifested as a laudable respect for knowledge. In an era when all that is required to be acceptable members of the chattering classes is to utter various shibboleths, James held the line. He believed that you also needed to do your homework.

That he had memorised his Marvell and Yeats, learned medieval Tuscan to translate Dante’s Divine Comedy, read T.S. Eliot and George Eliot with equal enthusiasm, meant that when he wished to be flippant he could be, knowing that the lead weights of scholarship would return him to solid ground. He was able to riff so wonderfully because he had learned so well the instrument on which he played; he was able to improvise because he had so many remembered scores to hand. Agree or disagree with his opinions, the avidity and dedication with which he accumulated knowledge raised him above an era when all the urgent questions are asked and answered within small bunkers of mutually reinforcing certainty.

Perhaps all generations suffer from the sense that they are a demographic declension from those who came before (which explains why our reverence for them coexists with the urge to patricide or matricide), but with news of James’s death it really does feel like someone larger in style, spirit and learning has exited the stage.

“A living culture,” he once wrote, “is the whole thing.” The television programs as well as the lyric poetry; the sporting heroes and the opera divas and the cinema auteurs. Few did more than Clive James to democratise the criticism of culture. Yet few brought such demanding standards to bear in doing so.

It may look, from a distance, as though James favoured the fruits of the old world over those of the new. I would prefer to think he was doing the latter the honour of linking it, via sheer enthusiasm and intellectual range, to the former. He joined the Australian village to the wider world, making it possible for future explainers to stay proudly local.