Clive’s lives

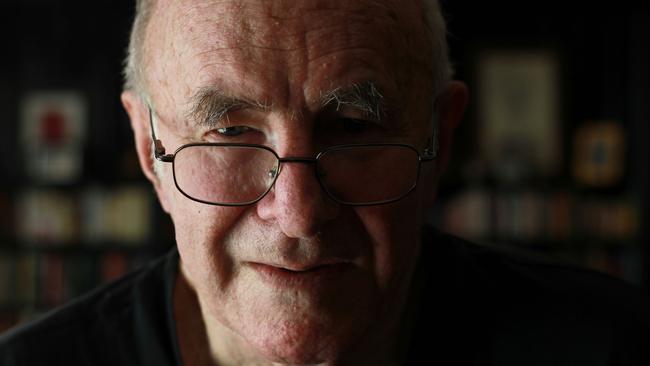

He is about to turn 80 and he will never return home, but Australia remains Clive James’s secret energy source.

How strange, to access your own obituaries. Yet Clive James, who has trembled on the threshold of non-existence for so many years now thanks to cancer and then the experimental treatment that deferred that cancer’s inevitable outcome, has enjoyed numerous opportunities to see his life and work written of in the posthumous tense.

All of which makes the occasion of James’s 80th birthday this coming Monday, October 7, a happy surprise and minor miracle of endurance, something of a living wake. I picture him, wheelchair-bound, plate of cake balanced on lap, navigating the mourners as they share war stories and reheat old gossip, or else land a barb at his expense, safe in the knowledge that some sharper rejoinder is unlikely to be returned.

Like any notable woman or man — someone who has cluttered up the landscape, whether cultural, political or social, for a decent amount of time — there will be no definitive position among the gathering about the accomplishments of the not-quite-departed. There are too many facets for a one-dimensional view.

And having tracked the wax and wane of many reputations, like that of his beloved Philip Larkin — subject of a recent volume of essays, Somewhere Becoming Rain, who went from national poet to despised racist and misogynist, back to revered creative figure over the course of three decades — James may well be sanguine about this ambivalence. Perhaps he recalls Plutarch on Alcibiades: “They miss him and hate him and long to have him back.”

The lesson of James’s expatriate generation — one that took the vigour and raw ambition of mid-century Australia and used it to storm the ramparts of the old world — is that even success can come to look like failure over time.

The revolutionary becomes the staid bourgeois. The trickster becomes the conformist. The upstart becomes the establishment figure. Few from Australia inhabited the countercultural moment of the 1960s and 70s with the intellectual elan of Robert Hughes, for instance. Yet he ended his days, in the eyes of many, as the critical equivalent of an old man shaking his fist at passing clouds.

Germaine Greer is another whose contribution to emergent feminism was as remarkable for its courage as its cogency. Still, despite formidable achievements she has fallen out of step over time with fresh iterations of feminist thought. And if your career is built on pushing boundaries, as comedian Barry Humphries’s has been, when those same boundaries are topped with razor wire and policed around the clock, your days as a professional provocateur are numbered.

This is not to exonerate such figures for the obduracy or untimeliness of their opinions, nor is it intended to drive one more nail into the coffins of their status. It is to acknowledge the inevitable, sine-wave nature of renown. It is to accept that new generations gain their victories by dethroning older, acknowledged leaders — and that these will be deposed in their turn.

If the proper task of criticism is to anticipate and argue for those aspects of a career that may survive these predictable convulsions, the life and work of Clive James is a complex gift. On one hand, James embraced fame in its high-fructose corn syrup form — that of celebrity. He is known as much for his long tenure as a television host as he is for his poetry and criticism. He hobnobbed with movie stars and royalty. He dignified a superficial version of repute by associating so closely with it.

But beneath all this, the immense ballast of proper work: half a century’s labour in critical thought and creative endeavour. Essays on literature, poetry and culture that combine formal rigour with exuberant judgment; the invention of a new field of diagnostic inquiry into television — currently the dominant art form of our age, in part thanks to his buoyant attentions — along with satellite efforts in fiction, travel writing, memoir.

And then there is poetry. Begun as a droll effort to reconfigure Georgian era witticism to comment upon the same age of celebrity that threatened to swallow him, James’s verse evolved into a mature investigation into the ways words and ideas might marry, merge, and describe a life of ramifying complication and looming melancholy.

Translation, too, with its efforts at fretting old beauties to a new moment — enlivening forgotten and overlooked texts, or books loved to death by generations of idolaters and exegetes, in ways that illuminate our current situation — while revealing for contemporary generations the undaunted brilliance of those, such as Dante, who remain tuning forks for cultural vitalism in the West.

I do not think James is supreme in all these fields; I think he is supreme in the energy he brings to bear on them. He is master of having a go: a DIY renaissance man who applies as much chutzpah as diligence in applying his innate talents to those enthusiasms that have punctuated the long arc of his career.

What will survive of James’s work are not its metropolitan aspects. Though he moved to London young and made Cambridge his home, it was the writer’s Australian upbringing that lit the long fuse of his ambition and rendered him unique in a culture ludicrously replete in smart and gifted scribes.

The shock of his arrival resides, or course, in unpromising beginnings. The childhood in Sydney’s suburban Kogarah, sole offspring of a war widow in straitened circumstances seems a universe away from the memoirist who went on to conquer the city that drew in and raised up everyone from Samuel Johnson to TS Eliot.

The world he describes with such adoring attention to detail in the pages of Unreliable Memoirs is lost to us now, cocooned in our McMansions or svelte, inner-city Sydney terraces. But that inexhaustible story — for all its jolliness a plangent book, haunted by the ghost of a father who never returned from war in the Pacific — constitutes a lavish and unimpeachable act of reclamation.

His is a world of outdoor dunnies and Technicolour film, of billycarts and filterless cigarettes and Jaffas and the modern magic of planes bellying up from Charles Kingsford Smith. It proceeds under the spell of its author’s longing — for it is the world he gave up in order to become his future self.

Above all, it is a book of appetites: for experience, for sex, for ideas, for talk, for friendship, and for love. This desire — unfulfillable because the one figure who could fill the void at its subject’s heart, who might provide a counterweight to the young man’s furiously unfocused drive, was forever removed from the scene — is the engine that drove him from his suburban origins and into another world. Every hello in the pages of Unreliable Memoirs is really a farewell.

For me, the memoirs’ spell is broken around halfway through May Week Was in June, the third in his initial trilogy, following on from 1986’s Falling Towards England.

That is that point where James’s ego begins to be validated by the wider world, rather than comically rebuffed. But if success spoiled Clive James’s autobiographies, it opened the door to those large experiments that established his fame.

And when I say experiments, that is what they were, at least at first. Those early essays for The TLS, New Statesman and other journals of higher criticism during the 70s started out as efforts to avoid completing his Cambridge doctorate. By all accounts, James has been consummately professional in his literary journalism, yet his pieces were evasive manoeuvres that only gradually became a main event. That he was able to parlay reviewry, even then an activity marginal to the broader culture, into a media career that lasted decades, is a testament to his ambition and fearlessness.

It is also, however, a testament to his appetite for adulation. The accomplishments of a TV career may have paid the bills and raised his currency in the new economy of the visual, but they obscured for a long time those more sincere efforts for which he now wishes to be remembered.

Looking back, it’s clearer to see now what happened. At the very same time James was becoming a fixture in people’s minds, his nasal deadpan developing into a trademark, the creative artist in James was venturing to dismantle that same persona.

This can be seen in the evolution in his fiction. Brilliant Creatures, James’s debut novel, published in 1983, reads like the banter that flew across the table at those legendary long lunches regularly held by the likes of Martin Amis and Peter Porter in London’s Soho (indeed, the novel contains long descriptions of such lunches). Even though James has described the book as “a box of borrowed clothes”, his voice is so present and clearly his own that it is difficult to read it as anything more than embroidered autobiography.

The Remake (1987) is less broad in its humour, more intimate. Even though it is written in the first person it feels further from the James we know so well. By the time his Bollywood novel, The Silver Castle, arrived in 1996, the author had moved even further towards the sidelines.

The prose may have been an artful pastiche of Amis Jr, but the obtruding sense of self that interrupted his earlier fictions has been largely dispersed.

In poetry, too, James moved crabwise into seriousness. His earliest works were mock 18th-century satires. They were funny, ribald and self-satisfied; their heroic couplets were brought down like a beer mug on a tavern table.

But illness and a growing sense of mortality modulated the smug virtuosity of this early work. James the persona is still present, the jokes are still set off like little firecrackers along the poetic line, but warmth begins to crowd out mere heat.

A hinge poem in this respect is 2004’s My Father Before Me, which relates a visit made by the poet to the Sai Wan War Cemetery in Hong Kong, where James’s father is interred.

Despair will ebb when I leave you for dead

Once more. Once more, as I get up to go,

I look up to the sky, down to the sea,

And hope to see them, while I still draw breath,

The way you saw your photograph of me

The very day you flew to meet your death.

Back at the gate, I turn to face the hill,

Your headstone lost again among the rest.

I have no time to waste, much less to kill.

My life is yours, my curse to be so blessed.

The poet is still, inimitably, James. But now the self that asserted itself so ruthlessly and well in achieving certain aims is obliged to confront another, implacably silent. In the face of such a charged absence, the energy and effort that have driven the poet all his life are seen in a new light. They are a mixed blessing — even a curse.

What if James’s freneticism has been an effort to live for two? To make amends? To assuage guilt. Wearing his critical hat, James once wrote of the anti-Semitic novelist Louis-Ferdinand Celine that only in his masterpiece, Voyage to the End of the Night, did the poison of the French author’s thinking dissolve in the acid of art.

Likewise, it was only in the growing awareness of the enduring grief he felt at his father’s loss, bolstered by the sense of his own illness and mortality, that unravelled the artful, jokey, egocentric projections he had played to the hilt for so long.

This is a hard and creditable turn in awareness. It served to deepen his poetry, culminating in last year’s moving book-length poem, The River in the Sky, and it unshuttered aspects of James’s personality that had been long hidden from view. James always agreed with his critic-hero Edmund Wilson that “an acquaintance with the great works of art and thought is the only real insurance against the barbarism of the time”. It is of a piece with the aesthetic conservatism that has been a hallmark of James’s thought — a sense that culture was the long game that should ignore momentary fevers in the present.

But this accumulated knowledge is only a gathering of other men’s roses unless there is some animating wisdom to shape them into something new.

In the first act of his career, James revealed himself to be one of the sharpest and generously enthusiastic critics of his generation.

This wide learning and range of reference lent gravitas to even his hammiest TV efforts, the scholarly iceberg lurking beneath cocked eyebrows.

But it was only relatively late in life that James renegotiated his pact with those poets, authors and thinkers — the musicians, filmmakers and artists — whose best efforts he had lauded, anatomised and absorbed.

He descended into a personal darkness and found that in this penumbral realm those works he had celebrated glowing like diodes (the image belongs to James). His orientation shifted, his art did so accordingly.

On the occasion of his 80th year — an age no one, least of all he, expected to see — it is worth noting and celebrating this shift. Back in 1974, James reviewed Philip Larkin’s volume, High Windows for Encounter. He was uncharacteristically direct, awe-struck by the slim collection.

“The total impression of High Windows,” he wrote, “is of despair made beautiful. Real despair and real beauty, with not a trace of posturing in either.”

“The poems which one had thought of as characteristic turn out to be more than that,” he continues, “or rather the character turns out to be more than that.”

Perhaps that is what we should remember, here at the extended wake for a quintessentially Australian cosmopolitan: his character has turned out to be more than that.

Geordie Williamson is The Australian’s chief literary critic.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout