Clive James: a brilliant career constructed from contradictions

For decades, Clive James exploited multiple media with swaggering intellect and exhibitionism.

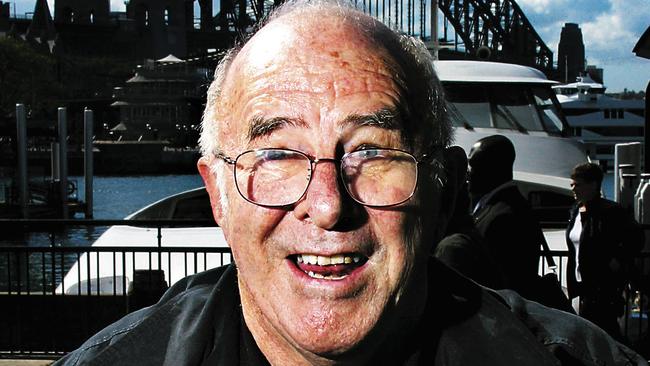

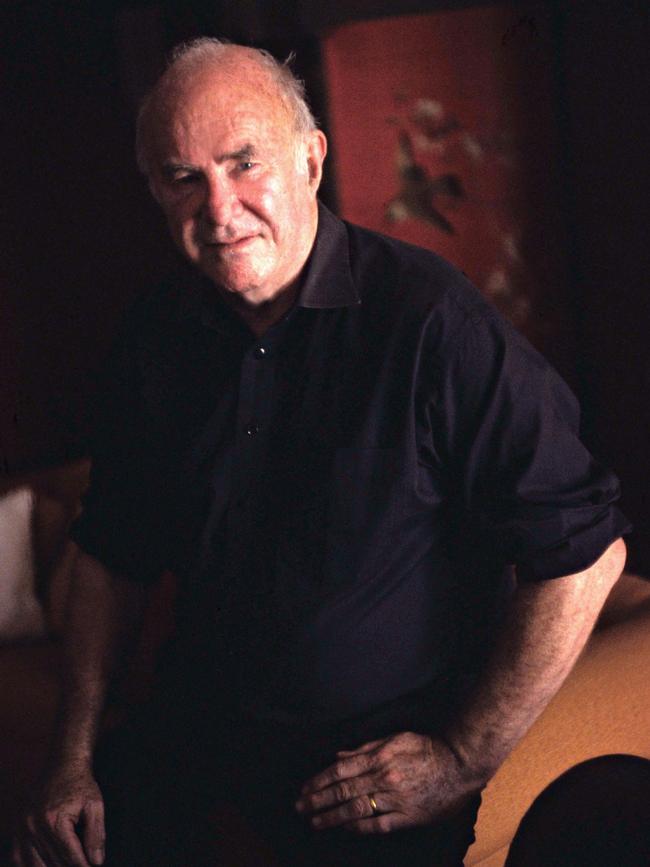

Clive James — author, poet, essayist, journalist, and broadcaster and TV host — constructed a brilliant career from contradictions, a template he perfected in recent years when his creativity blossomed even as he lay dying.

For decades James cleverly mixed “high” and “low” culture, exploiting multiple media in a swaggering display of intellect undercut by exhibitionism.

He was the writer who doubled as television performer, the poet as comfortable with Dante as Game of Thrones, the literary critic renowned for his television analysis, the expatriate Australian who explained culture to the world.

Finally, he was the terminally ill patient who not only declined to die but who produced some of his finest work in his final years.

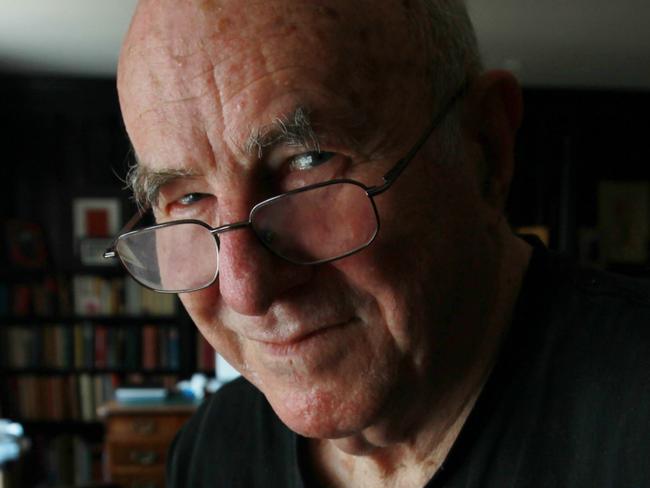

James’s long goodbye began in 2010 when he was diagnosed with leukaemia and “several lung diseases”. In 2011, he went public and spent the rest of his life writing poems, adding to his memoirs and giving a series of interviews in which he talked of how his death sentence had given him greater clarity and focus than ever before.

He may have been overstating it. James had never been a slouch, throughout his life demonstrating a determined and disciplined approach to his work, one albeit masked by an intellectual playfulness, self-deprecating humour and a willingness to send himself up.

He had a great appetite for knowledge and he was one of the most productive public figures of his generation.

He spent more than 50 years away from his home country but he avoided the temptation of sniping from afar and in his later years especially was full of praise of the Australian way.

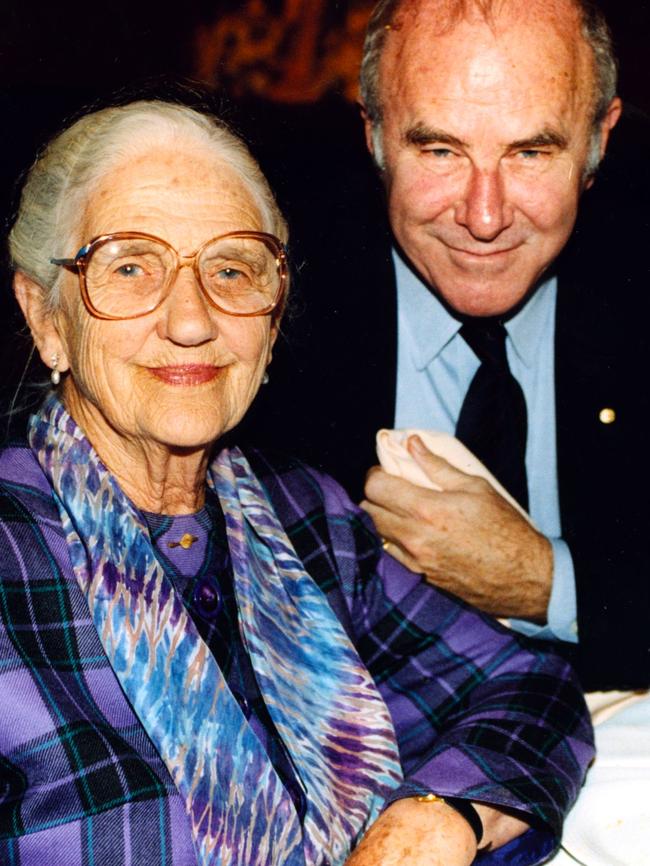

James had unpretentious origins in southern Sydney, where he was brought up an only child by his mother, his father having been killed in an air crash returning from a Japanese prisoner of war camp after World War II.

Originally named Vivian, he changed his name after Vivien Leigh played Scarlett O’Hara in Gone With the Wind and “the name became irrevocably a girl’s name no matter how you spelt it”, he wrote in Unreliable Memoirs(1980).

He was educated at Kogarah Primary — where he realised he could read with ease despite being a reluctant pupil — and Sydney Technical High School. He could have attended Sydney Boys High School but chose Sydney Tech.

It was an education he relished.

Years later he told an audience at Sydney University when he received an honorary doctorate of letters that: “When my generation of ambitious Australian expatriate writers got to Fleet Street in the early ’60s, it was already evident that the excellent Australian state school system had given us a big advantage over the other locals.”

Thanks to a war orphan’s scholarship, he went to Sydney University where he lost his cluelessness about modern history and discovered literature. As literary editor (and co-editor) of student newspaper Honi Soit, he was the first to publish poet Les Murray.

Literature was king on campus at that time, in a period when students were not yet radicalised by Vietnam. James was a driving force in the annual student revue, drank with the Sydney Push and tried — usually in vain — to act like a sophisticate.

He was obsessed with words and on one occasion startled friends when he announced that he and they were “intellectuals”.

The confidence led him to a year working at The Sydney Morning Herald before sailing in 1961 for England where he began a dissolute life, drinking and refining the art of bohemianism.

After three years he pulled himself together and won a place at Pembroke College, Cambridge, to read English literature.

He was a member and later president of the Cambridge Footlights, the university revue that put many entertainers, such as Peter Cook and John Cleese, on the way to a career in showbiz.

James’s growing prominence in satirical circles attracted the attention of literary editors in London and he had soon had bylines in the Listenerand the New Statesman, among others.

In 1972 the assistant editor of The Times Literary Supplement, Ian Hamilton, asked James for 2000 words on the US critic Edmund Wilson.

He wrote 11,000, of which 10,000 were published. In those days, the TLSmaintained a tradition of anonymity among its contributors but the novelist Graham Greene insisted on knowing, writing to ask for the identity of the rising new star so that he could congratulate him.

“Flatteringly avuncular, Greene suggested that I might consider the discursive critical essay as my destined field of operations,” James wrote.

“The piece wasn’t as long as the letter I wrote in reply, which was probably the reason I never heard from him again. The success of the piece on Wilson was the beginning of my confidence in a tactical approach to print journalism by which I might get away with combining the apparently antagonistic roles of wiseacre and smart alec.”

READ MORE: Geordie Williamson — Clive’s lives | Troy Bramston — Clive James’s mini-epic a major flowering of ‘honest, reliable memoirs’ | Trent Dalton — Clive James: life, death and my next great work | Climate alarmists cop a Clive James savaging | Clive James essay — Western climate change alarmists won’t admit they are wrong

James soon began to establish himself as one of the most influential literary critics of his generation. He believed that a cultural commentator could only benefit from being as involved as possible with his subject, and over as wide a range as opportunity allowed.

The Observer hired him as a television reviewer in 1972, a weekly column that lasted 10 years. Selections from the column were published in Visions Before Midnight, The Crystal Bucket and Glued to the Box. The job turned his fortunes around because it represented a regular wage pay slip for the first time and allowed him to write more widely.

He became a proficient, although somewhat quirky, television performer and wrote and presented numerous series and specials. He pioneered the postcard style of travel shows and inspired the series Fame in the Twentieth Century.

Throughout his TV engagements in the 1970s and ’80s, he continued his work as a critic, author and poet. He had written poetry for Honi Soit, but his 1976 satirical verse, Peregrine Prykke’s Pilgrimage Through the London Literary World, made the city’s literary types look up. It was said that many leading figures were disconcerted by appearing in it, and more disconcerted if they were left out.

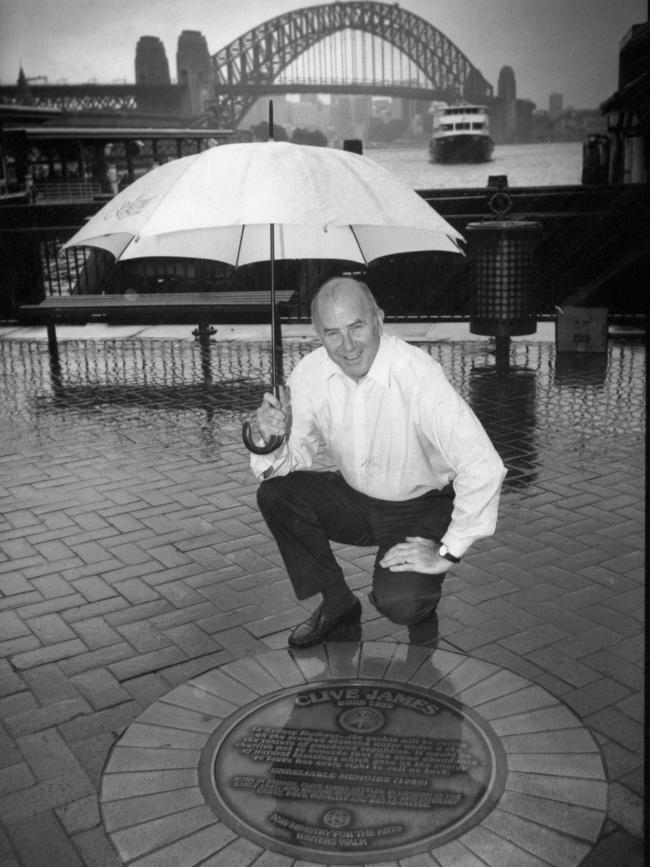

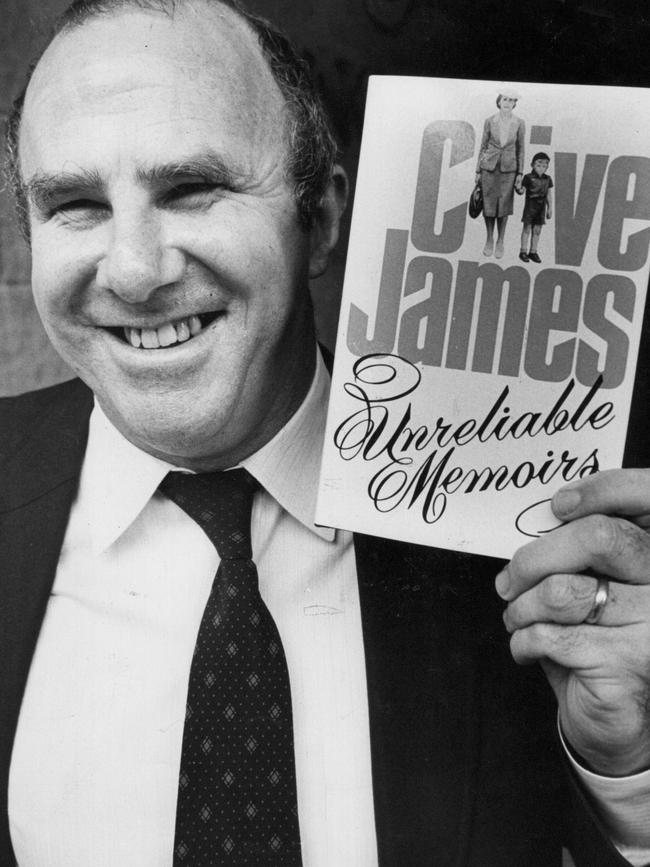

His first autobiographical book, Unreliable Memoirs (1980), was a great success and very funny — and eventually ran to more than 60 reprintings. Two further volumes of autobiography, Falling Towards England (1985) and May Week Was in June (1990) were consolidated in an omnibus edition, Always Unreliable (2001).

North Face of Soho (2006) was the fourth and last of his autobiographical series — although in early 2015 he indicated that he hoped to write another volume of memoir. The works were factual with some fiction thrown in, often to disguise a subject’s identity.

“The evidence rapidly mounted that there was a new contender in town for the post that every literary editor needs to fill: the trick pony who can work like a draught-horse,” he said of his early efforts.

A secret to his writing success, he told The Australian’s Europe correspondent Peter Wilson in 2006, was to write the way he spoke. “When I write a book, I speak it aloud. I think, ‘How would this go over if I were reading it out to an audience?’ … I tried to give each piece everything, composing it as if it were a poem.”

He found time to write four novels (the first, Brilliant Creatures, was a bestseller) and several books of poetry, including The Book of My Enemy (2003), and in April 2015 published Sentenced to Life — a collection of poems about his illness and impending death. Asked towards the end of his life which element of his career had brought him the most satisfaction, he replied: “The poetry, for me, is always the centre of the whole business. It’s where I started. It’s probably where I’ll end.”

Even so, it was TV that brought him into the consciousness of Australians and Britons.

He started in the late 1970s as a guest commentator on various chat shows and as an occasional co-presenter with Tony Wilson on So It Goes, a pop music show. When the Sex Pistols made their TV debut, James recalled: “During the recording, the task of keeping the little bastards under control was given to me. With the aid of a radio microphone, I was able to shout them down, but it was a near thing … they attacked everything around them and had difficulty in being polite even to each other”.

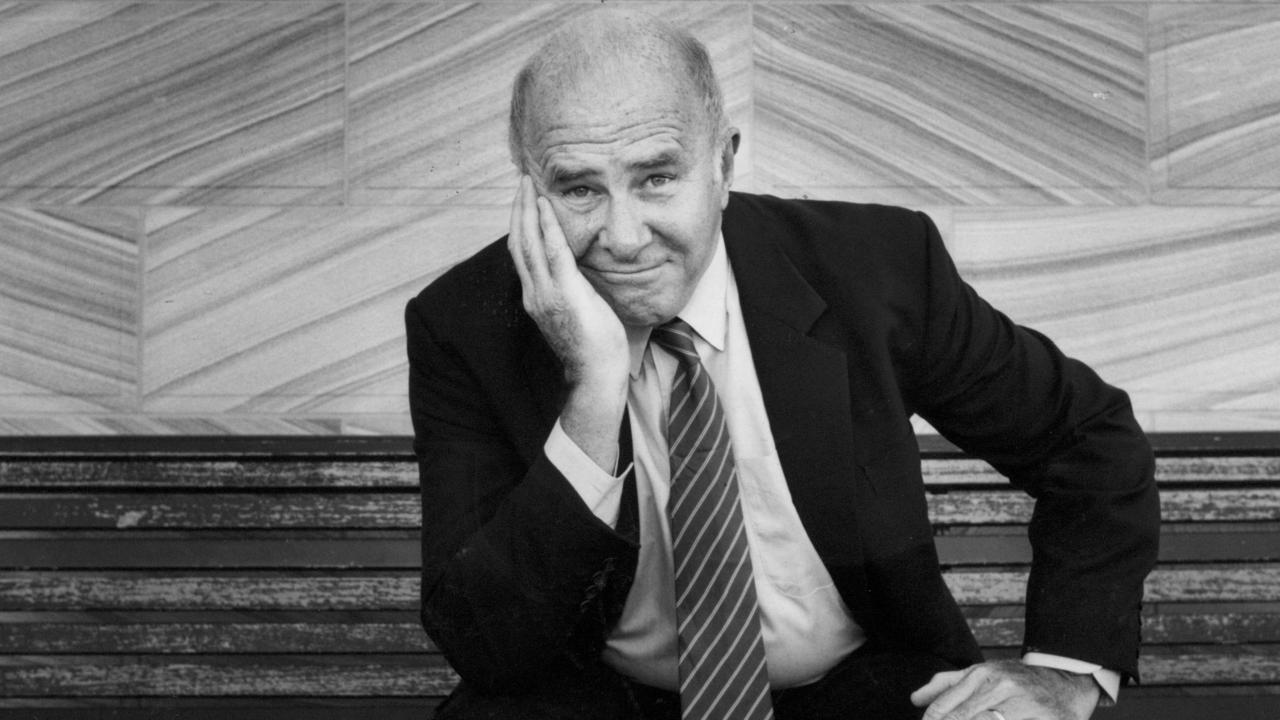

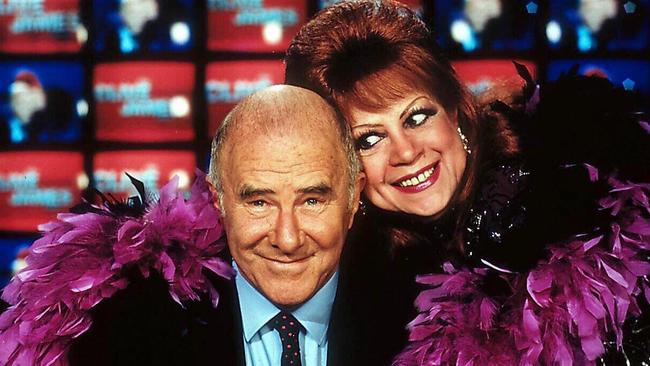

He had his own show on ITV, Clive James on Television, in which he lampooned overseas productions for naivety and/or cultural oddities. He moved to the BBC in 1989 to host Saturday Night Clive (later Sunday Night Clive), a popular chat show sprinkled with James’s amusing commentaries. Australians laughed along with the somewhat rotund, balding performer and had little awareness of the literary sensibility and classical knowledge that lay behind it.

In 1995 he set up Watchmaker Productions to make shows for ITV. But by the time the show’s name had become Monday Night Clive, he realised it was time to move on — especially since he wanted to interview serious actors and performers while the network preferred a Spice Girl.

He quit TV in 2001 to become chairman of the internet enterprise Welcome Stranger until he left to head one of its subsidiaries, clivejames.com, one of the world’s first personal multimedia websites.

In his spare moments, he began writing in earnest. The 2000s saw James publish several collections of essays, but his grand opus was Cultural Amnesia (2007), a book with a vast scope whose 800 pages touch on people and ideas from the 20th century. It contains more than 100 essays on artists and thinkers whom he judged to have contributed in some way to our cultural heritage and to the world of ideas. “This book is as good as I can do. I can’t write better than Cultural Amnesia,” he said.

His literary commentary and a six-part Radio National series he recorded with the Australian poet, the late Peter Porter, demonstrated his brilliance as a communicator. He and Porter ranged over a landscape of memory littered with the books, poems, music, painting and culture that had shaped their lives. Both men were exemplars, of whom writer David Malouf wrote: “Australians of a certain turn of mind are literary beyond the imagination of most Europeans. “

In James’ case, his scholarship was not so much worn lightly as played with, tossed about with alacrity, and kicked into the park, exploited with insouciance. He was a consummate performer — like fellow expats Germaine Greer and Robert Hughes — and excellent on television.

One of James’s lesser known talents was songwriting. In collaboration with musician Pete Atkin, the pair released six albums: Beware of the Beautiful Stranger (1970), Driving through Mythical America (1971), A King at Nightfall (1973), The Road of Silk (1974), Secret Drinker (1974) and Live Libel (1975).

They were reissued between 1997 and 2001 following interest stirred by Steve Birkill who complied an internet mailing list, Midnight Voices. James appreciated Birkill’s effort and wrote that “one of the midnight voices of my own fate should be that the music of Pete Atkin continues to rank high among the blessings of my life”.

A double-album of songs The Lakeside Sessions: Volumes 1 and 2 was released in 2002. Another, Winter Spring, was released in 2003.

On politics, James identified himself with the Left but was strongly opposed to communism and totalitarianism. In 2006, interviewed by The Sunday Times, he said: “I was brought up on the proletarian Left, and I remain there. The fair go for the workers is fundamental, and I don’t believe the free market has a mind.”

He didn’t like the trend towards privatisation introduced to Britain by Margaret Thatcher. He said in 1991: “The idea that Britain’s broadcasting system — for all its drawbacks one of the country’s greatest institutions — was bound to be improved by being subjected to the conditions of a free market: there was no difficulty in recognising that notion as politically illiterate. But for some reason people did have difficulty in realising that it was economically illiterate too.”

After Cultural Amnesia was published, he was still asserting a leftist outlook though worried about left-wing blindness to the rise of Islamist extremism.

“The thing to be pessimistic about is that as we advance further into liberal democracy, and rights are more and more equally shared between men and women and every race, the danger is that you’ll lose a grip on just how valuable that is,” he told The Times in 2006.

“You’ll think that’s automatic, that it comes like the rain, but in fact it’s part of a vast historic structure that took time. And it’s part of the writer’s job to remind the young of this.”

His contribution to journalism was wide and varied. He wrote for Commentary, the New York Review of Books and the New Yorker, The New York Times, the Los Angeles Times and the Atlantic Monthly. In Britain he wrote for the TLS, the London Review of Books, the Guardian, the Spectator and the Liberal.

In Australia he contributed to the Australian Literary Review, The Weekend Australian, the Australian Book Review and the Monthly.

The Australian’s Luke Slattery wrote in 2013 that “Nothing is beyond him. His byline, read regularly on both sides of the Atlantic, is synonymous with the cosmopolitan style of criticism that is highbrow without being high-toned, at once serious and endearingly droll”.

But it was as a poet that James really wanted to be remembered. In the early years his poems were often dismissed as light rather than literary. In 2000 he wrote In Praise of Marjorie Jackson (“As the Lithgow Flash shot through like the Bondi Special/into the language and Australia rose to its feet”). In 2004 it was In Memory of Shirley Strickland de la Hunty (“The bobby-dazzler won’t be back/Who ran for love and jumped for sheer delight”). But, his illness lent gravitas and poignancy to his work and by the time The New Yorker published Japanese Maple in 2014 James was being lauded as a significant poetic talent. The year before he had stunned critics with the release of his translation of Dante’s The Divine Comedy. Peter Goldsworthy wrote in The Weekend Australian that James had a perfect skill set for this work:

“He is a poet of great technical dexterity, his writings range effortlessly across the registers from the vernacular to the philosophical to the comic, and his erudition can surely channel a 13th-century consciousness better than most”.

In early 2015, as Sentenced to Life was published to acclaim, James was already onto the next project — a sequel to Cultural Amnesia.

The ultimate contradiction in this complex man was that while he wrote and spoke countless thousands of words about himself and his life, he was essentially a private person. He always said that on television he only ever played himself, but there were many in his global audience who were never quite convinced of that.

In 1992 James was made a member of the Order of Australia, promoted to AO in 2012; in 1999 he was awarded an honorary doctorate by Sydney University. In 2003 he received Australia’s leading poetry award, the Philip Hodgins Memorial Medal. He was an honorary fellow of the Australian Academy of the Humanities.

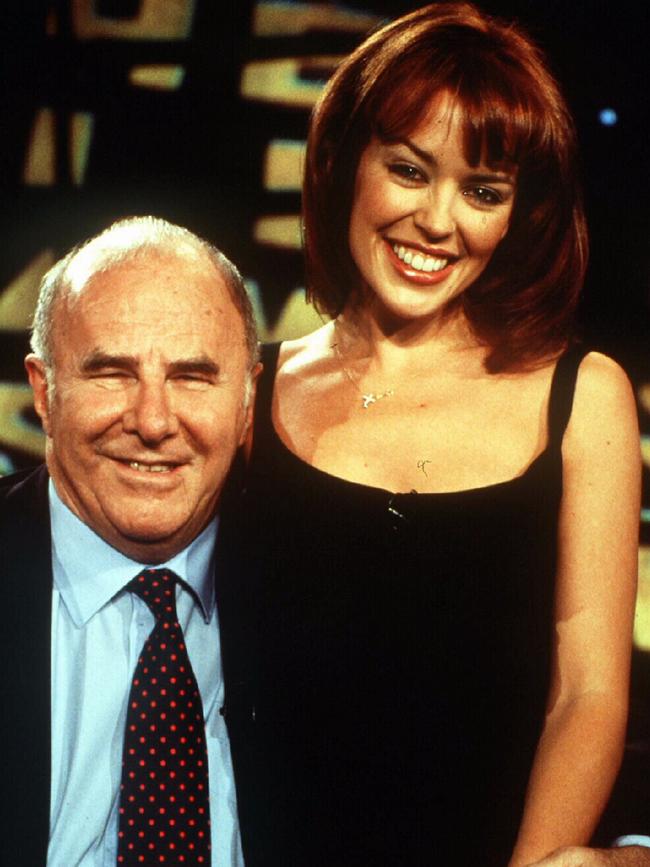

For most of his long marriage to academic Prudence Shaw, James lived in London while his wife lived in Cambridge where he visited at weekends. After his diagnoses he moved to Cambridge, although the marriage was severely strained in 2012 after revelations of a long affair with a Sydney woman, Leanne Edelsten, the ex-wife of controversial Sydney doctor Geoffrey Edelsten.

In Cambridge in March 2015, he told The Weekend Australian ’s Trent Dalton: “Yes, I was a deceiver. I was faithless. I’m not now. But then, on the other hand, I’m an old man, so how can I be? I live to regret my young transgressions. But I try not to lose sight of the fact they might have been part of my youthful energy …(Prue and I) say to each other, ‘We have a combined age of 150 years’. It’s kind of extraordinary that we are still involved with each other. And it’s true. We’re involved.”

James is survived by Shaw and their daughters Claerwen and Lucinda.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout