Christian Marclay calls "time please" with artwork The Clock at the MCA

TIME is used to remarkable effect in Christian Marclay's video work The Clock at the newly reopened Museum of Contemporary Art in Sydney.

A WELL-KNOWN French dictionary defines time as the indefinite medium in which events succeed each other in an irreversible fashion. The formula is characteristically Gallic in its combination of precision and abstraction, delightfully economical in one sense but also perhaps raising more questions than it answers.

For time is one of the most fundamental yet ineffable aspects of human experience, and nowhere do we encounter its mystery more urgently yet uncomprehendingly than in the reality of growing old. To the young, despite what they know theoretically, age remains an ontological category: young people and old people are inherently different. They cannot imagine that a boy will be an old man or that a bent old crone was once a pretty girl. It is only much later we begin to perceive the work of time quite clearly in the bodies and minds of the people around us, as though instead of seeing the world as a series of stills, we were watching it in moving pictures.

Meanwhile, our lives are spent waiting for things - time stretching out as we desire or fear what is to come - or remembering them, trying to reconstruct experience from a past time suddenly as flattened and compacted as a crushed tin can. In between there are rare moments of presence, like a kind of grace in which the distorting perspectives of past and future are forgotten.

From the point of view of God, as philosophers and theologians have often observed, there can be no time: the divine consciousness is all presence, or sees everything that for us unfolds in time as though simultaneous. But what may be a state of blessedness for immortal beings would be a curse for us mortals: life would be unbearable if our own death and the ends of those we love were always present to our consciousness. We must experience life sequentially and forget much of what we have lived through for our lives to be tolerable.

Time, in all its aspects, is naturally a pervasive theme in art, but it is also a crucial factor in the structure and the nature of different arts. Thus music is inherently temporal; it must develop through time with its beginning, variations and repetitions, and then climax and ending. Stories too - written, performed or filmed - have beginnings, middles and ends, while paintings, as Charles Le Brun wrote, have but a single instant and must compress everything into a single view.

In novels, plays and films there is always the question of the relation between narrative time and the implied temporality of the underlying events. The order in which these are related is the most obvious question. Homer is, as far as we know, the author of the most momentous innovation in this regard, and one that has become a staple of cinema, the flashback: the Odyssey begins near the end of the underlying timespan covered by the story, and the famous adventures of Odysseus on his travels home are told in a long flashback - which Homer also takes as an opportunity to switch from the basic third-person narrative into the more vivid first-person.

The Odyssey also has to deal with the question of simultaneous sequences of events in separate places, and with the question of pace or timing. The underlying events related in a novel take place through a certain length of time; in the telling of the story, however, years can be passed over in a page or even a few lines, while a few hours can stretch to many pages: thus Proust passes over the years of the Great War relatively briefly, before the narrative slows down dramatically for the long episode of Prince de Guermantes's party.

In writing and cinema, pacing is a complex matter, for acceleration can convey urgency or excitement, but slowing down, stretching time, can also evoke suspense and build anticipation. Here, however, there is an important difference between literature and cinema, for the speed or slowness of writing, as already suggested, is essentially relative, while in cinema these things can, in theory at least, be literal. In practice, all films will omit certain periods of time - since the underlying events are likely to take more than two hours - but literal pacing, even separated by temporal elisions, can be used to create a particularly naturalistic effect.

Popular films also use literal time for suspense: it would be interesting to measure the duration of all those scenes in which a hero supposedly has two minutes to defuse a bomb or 10 minutes to save the world. Is the film time literal or is it really, as one suspects, stretched to increase the effect of suspense?

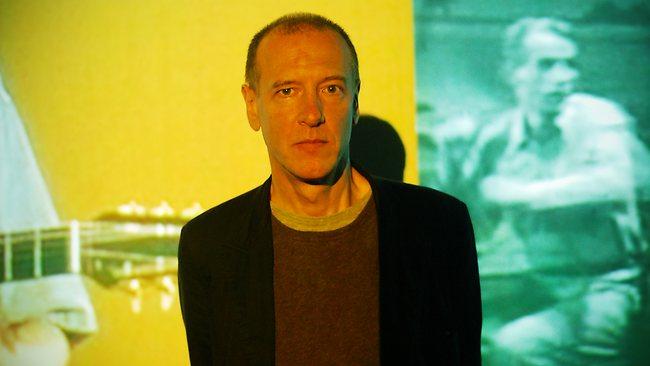

Literal time is used to remarkable effect in Christian Marclay's video work The Clock at the newly reopened Museum of Contemporary Art in Sydney. Marclay's idea is simple though sophisticated, but an extraordinary amount of work went into its realisation. He has edited thousands of clips from films, famous and obscure, creating a 24-hour long anthology of moments in which characters look at or respond to clocks and watches. All these clips, moreover, are edited into sequence according to clock time, and the projection is set to match the time of the place where the video is shown. In effect the whole work constitutes, as the title suggests, a kind of clock. Having just got off a plane after the time-zone scrambling experience of a flight home from Europe and with a country train to catch a couple of hours later, I was certainly in the right frame of mind to encounter a work about temporality.

Trains and stations appear often, not only because we tend to look at watches disproportionately often when trying to catch public transport but because the tyranny of clock time itself is related to the development of modern forms of mass transit, as well as to the factories and offices to which they convey workers. Until the industrial revolution most work, not only agricultural but artisanal and even clerical, was governed by the availability of natural light and by the annual rhythm of the seasons.

Time, as a result, was elastic: working days were longer or shorter through the course of the year, and the seasons imposed periods of labour and others of comparative idleness. It was more important to know it was an hour before sunset than that it was any particular number on the sundial or the clock. But as artificial lighting allowed working hours to be standardised and the efficient operation of large-scale manufacturing required such regularisation, we came to be ruled by the inelastic time of the clock.

Appointments, meetings, deadlines are all evoked - all the moments at which a character in a film is likely to look at a clock or a watch - and in the course of the endless accumulation of micro-episodes divorced from their original contexts, we feel the association of mechanical time with anxiety and tension, although waiting can be infused with boredom as well as fear.

The section just before midday proved to be one of the most thought-provoking, as the tension built to an hour of the day which, like midnight, is charged with a special significance. The clips from films in which midday played an important part - among them, of course, High Noon - succeeded each other at an increasing pace to fit them in before the real midday; the almost millennial pitch of expectation reached a climax with the striking of clocks and Charles Laughton as the hunchback ringing the bells of Notre Dame, and was followed by a palpable phase of post-climactic detente.

Consideration is given not only to the mere sequence of times but also, more subtly, to associations of specific themes and motifs (death, trains, guns), frequently echoed between films that are in themselves quite disparate in style and sensibility. Marclay's work is thus a fascinating compilation that is a meditation on temporality and associated ideas and a reflection on cinematic style and convention.

The film lover will be constantly confronted by snatches of films at once familiar and unfamiliar, alternating between the extremely well-known and the very obscure.

Marclay's encyclopedic compilation is supported by an exhibition that is also devoted to the theme of time as registered in works of art. There are several interesting and suggestive works in this exhibition, including John Gerrard's large, elaborate and slow-moving digital images of industrial installations in a barren world; another that particularly stands out is the digital video by Daniel Crooks that was seen in the 2010 Biennale. This work, as I observed at the time, is a relatively rare example of digital technology being used really effectively: that is, doing something of intrinsic interest that could not be done in any other way.

Crooks starts with what is ostensibly a straightforward video of an elderly Chinese gentleman practising tai chi in a Shanghai park; but then the image begins to be altered, subtly at first, the limbs stretching, barely perceptibly, in the direction of their reach. Then the distortion gradually becomes more radical: the figure expands and doubles, as though in a metaphor of the mind's extension beyond the self and union with the breath, the chi of life.

Also notable, though rather less positive in its view of life, is a work by Jim Campbell that at first sight seems to consist of a grid of LED lights projecting random patterns of light on to the wall behind them. On closer inspection, however, it becomes apparent that these patterns compose the shadowy forms of figures in motion. So much is clear from the work itself; from the title Home Movies and the label we learn that Campbell has based this work on anonymous video footage of family occasions.

The original films are reduced to unintelligible silhouettes, like faint after-images of lives long gone, a melancholy reflection on the fallacy of our attempts to hold back time and mortality: for contrary to the persistent claims of those who sell cameras and video recorders, experience cannot be given durable form by direct recording but only by the distillation of art, which involves, as in a poem, its transmutation into a form artificial and impersonal.

Christian Marclay: The Clock; Marking Time

Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney, until June 3