Caravaggio: beyond the sex and death scandal

Too much has been written about Caravaggio by authors attracted to the sensational details of his life but naive about his work and methods.

We are perhaps surprisingly well-informed about the lives of early modern artists, largely because of a biographical tradition that begins with Vasari’s Lives of the Artists, first published in 1550 but reaching back to the time of Giotto. This invaluable source is a credit to the labours of the author and his concern not to let the achievements of his contemporaries and predecessors fall into oblivion, but ultimately it rests on the Renaissance conviction that artists were among the important men of each age and that their works were precious monuments of civilisation.

Vasari established the tradition of not writing biographies of living artists. Thus at the end of his life of Giorgione, he mentions Titian as a great contemporary Venetian, but explicitly notes that as a living figure, he is not included in the book. He did make one exception in that first edition, for his hero Michelangelo, who was simply too important to be left out. In the second edition in 1568, he extended this exception to Titian, changing the end of Giorgione’s life accordingly.

There is a gap in the biographical record for most of the second half of the 16th century, because Vasari had no immediate successor: the late Mannerist artists were more concerned with intellectual speculations than with anything as down-to-earth as biography; one result of this was that the following generation grew up with an aversion to theory. The 17th century did return to both theory and biography, however, and the result is that we possess in many cases two or more contemporary sources for each significant artist.

In Italy, the first of these new biographical collections was by Giovanni Baglione, whose Vite… came out in 1642 and covered the lives of artists working in Rome in the early decades of the new century. Later authors of “lives” include G.B. Passeri, writing in the 1670s and covering artists who died between 1641 and 1673, although the book was not published until 1772; J. von Sandrart, writing about northern artists (1675); C.C. Malvasia, who wrote about artists in Bologna (1678); A. Félibien, whose five-volume work came out from 1666 to 1688; R. de Piles (1699) and L. Pascoli (1730-36).

Most important of all, however, was Giovanni Pietro Bellori, whose set of lives came out in 1672 prefaced by a programmatic introduction on the concept of the ideal in art. One of the reasons for Bellori’s importance, as this suggests, is that he combined biography with a critical and theoretical perspective in a far more sophisticated way than any of his contemporaries. The other distinctive feature of his book was that it was highly selective: only 12 artists – nine painters, two sculptors and one architect – were included, although further individuals were to be covered in a projected second volume. The selection was not jingoistically Italian, either: it included three Flemings (Rubens, Van Dyck and Duquesnoy), and a Frenchman, Bellori’s friend Nicolas Poussin, possibly the most eminent painter in Rome at the time of his death seven years earlier.

The book was controversial for its omissions, particularly of the giant figure of Bernini, of whom Bellori disapproved. But one of the most interesting lives is that of Caravaggio, precisely because Bellori had such mixed feelings about him; in his youth, he had admired Caravaggio’s painting, but he had grown increasingly critical of both his method and his style as he matured intellectually. Yet for all his reservations, he still included him as one of the dozen giants of contemporary art. The text is well worth reading, and can easily be found online in translation with some useful notes by searching Bellori Caravaggio Witcombe.

Caravaggio is one of the most intriguing characters in early modern art and much has been written about him – too much, in fact, especially by authors attracted to the sensational details of his life but naive or superficial in their understanding of his work and of his method in relation to contemporary practice. One of the only new things added to our knowledge of Caravaggio in the last half-century is the probable discovery of his bones in a common grave near to where he is known to have died in the summer of 1610.

Annibale Carracci, whom we discussed last week, was Bellori’s hero among modern artists, the man he felt had found the true balance between vapid mannerism and literal, pedestrian naturalism. We thus know a great deal about Annibale as well, but none of it is sensational or dramatic. He was a quiet man, given to melancholy and suffering from depression in later life. Caravaggio, on the other hand, was wild, passionate and constantly getting into trouble as a result, as Bellori makes clear.

While Annibale was highly-trained and a draughtsman of genius, Caravaggio, as far as we know, never learnt to draw; but he had a natural talent for painting from life, and this is what was later controversial about his method, especially when it was eagerly adopted by other young men, often from the northern countries, who had not had the benefit of an Italian art training with its emphasis on drawing from life. He would set models up in the studio, as though for a photo-shoot, and once he had worked out the composition, have each of them model one by one in costume.

This method explains why his early pictures in particular are seen in close-up – because you have to be very near the model to see it in sufficient detail – and thus half-lengths, with a small number of figures seen in a shallow space and no background. The effect was strikingly naturalistic in one sense although also theatrical and artificial. To rival painters, however, the vivid naturalism seemed almost dishonest and the method itself was evidently inadequate for more complex commissions such as church interiors and large-scale frescoes.

This is one of the fundamental facts about Caravaggio’s career that escapes most popular writers on the subject. The other is the meaning of his choice of vulgar models – ruffians and girls and boys of the street. There is nothing irreligious about this choice, even though on a couple of notorious occasions commissions were rejected on the grounds of vulgarity. On the contrary, Caravaggio’s work is profoundly religious; his choice of common models was designed to bring the sacred stories into the world of everyday reality, but above all to emphasise the paradox of the spirit irrupting into the domain of the material and the banal.

But if his method and his choice of models were criticised by some contemporaries and later authors including Bellori, it was his personal behaviour that got him into trouble with the law.

It seems likely he killed another young man as an apprentice in Milan before he came to Rome. There, he was known for his bellicose behaviour, and was prone to declaring that all other painters in Rome, with the exception of Annibale, were incompetent dunces. A particular object of his scorn was Baglione, whose even-handedness in his later biography, the first of Caravaggio, is all the more commendable.

We still have police records of various other incidents, but the most serious mistake he made was in killing a well-connected young man after a tennis match in 1606; he had to flee to Naples, then to Malta where he became an honorary Knight of St John and painted the great altarpiece in Valletta, before getting into a brawl with one of the knights and being thrown into jail; escaping under mysterious circumstances, he came to Sicily and painted several important works there, apparently pursued by gangs of thugs hired by the family of the young man in Rome or the knights, or both. They finally caught up with him in a backstreet in Naples, and the wounds he sustained probably contributed to his death some months later.

The other source of popular fascination with Caravaggio is the homoeroticism of his youthful work in particular: the early picture of a boy with a vase of roses, his finger bitten by a lizard (c. 1594-96), juxtaposes the same symbols of sexual pleasure and the sting of punishment, probably in the form of syphilitic infection, as we saw in Bronzino’s allegory a couple of weeks ago.

Later pictures alternate between self-portraits in various guises and pictures of young boys who sometimes have, as has been pointed out before, an almost disturbing resemblance to his own features, recalling Freud’s theory about the relation of homosexuality to narcissism. Coincidentally, Narcissus is one of the very few mythological subjects he seems to have painted.

In earlier centuries, the emphasis was on actions rather than on orientation or disposition. But whatever Caravaggio got up to – and in spite of an allegation of sodomy in 1603 – no-one seems to have been especially alarmed. Rome in the artist’s day was a very unusual place, completely different from a bourgeois city in Flanders, for example. A considerable proportion of the population was theoretically at least celibate, from the Pope and cardinals to monks, nuns and priests. Meanwhile, in a city without a police force, prelates and other important people kept ex-soldiers and other adventurers as bodyguards; unmarried men who frequented an underworld of inns and bars where they were entertained by women and boys of the easiest virtue.

These are the people who appear more overtly as themselves in the work of Caravaggio’s French follower Valentin de Boulogne – soldiers old and young, women and youths of various ages, gypsies, drinking together and finding consolation for their hard lives in music. One such woman is said to have been Caravaggio’s mistress, although she also plied her trade in the Piazza di Spagna. After she drowned in the River Tiber – presumably murdered – the artist is said to have used her body as the model for the Death of the Virgin (c. 1604-06). The rumour got out and the commission was cancelled, but Rubens at once acquired the painting for the Duke of Mantua.

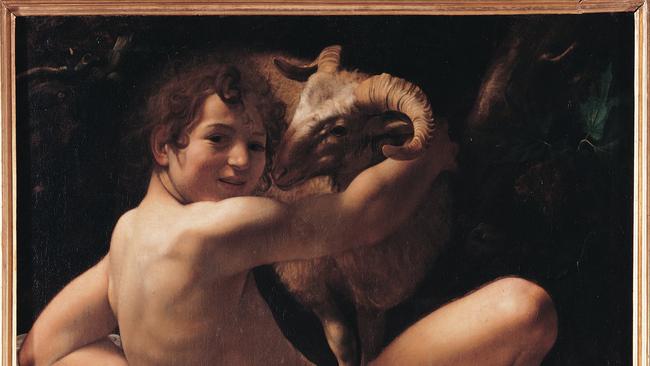

Meanwhile his servant boy and possible catamite Cecco modelled for the role of love in Amor Vincit Omnia (1601-02), as well as St John the Baptist with a ram (1602), both of which slyly allude to figures by Michelangelo in the Sistine Chapel. And although the artist’s great later works, such as the second Supper at Emmaus (1606) or the Raising of Lazarus in Messina (1609) have no room for erotic overtones, David with the head of Goliath (1610) presents his own by now worn and distressed features in the decapitated head, while David is one of the boys from the early paintings, only now turned into a figure of judgment and retribution.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout