Noel Counihan’s political art was dramatic, but changed nothing

The artist’s pieces certainly stand out, but there’s little evidence their messages changed the opinions of Australians in the Depression, World War II and Cold War eras.

Noel Counihan (1913-86) was an Australian artist of the mid-20th century whose most important work belongs to the years of the Depression, World War II and the ensuing Cold War period. He was a committed communist all his life – he died shortly before the collapse of the Soviet Union – and his belief in a simple and direct form of art capable of communicating with the masses inevitably collided with the pursuit of experimental forms by artists who considered themselves avant-garde.

There were bitter disagreements within the Contemporary Art Society, during the war years, between Counihan’s group and the modernists such as Sidney Nolan and Albert Tucker, associated with the so-called Angry Penguins movement. This was not, of course, the only instance of tension between the political left and the artistic avant-garde in the 20th century; on the contrary, it became a pervasive theme in the art, literature and cinema of several generations, from the time that Joseph Stalin suppressed modernism as bourgeois and instead enforced the propaganda art of social realism.

After the war it was the modernists who triumphed. Nolan, Arthur Boyd, Russell Drysdale and to a lesser extent Tucker achieved recognition and success in Australia and even internationally. Communist artists such as Counihan, Vic O’Connor (1918-2010) and Yosl Bergner (1920-2017) were all but forgotten, as indeed were other modern realists such as Arthur Badham (1899-1961) or Douglas Dundas (1900-81) – successively heads of the National Art School in Sydney – who have attracted more attention recently.

Counihan was fortunate to be supported by his friend Bernard Smith, who became the doyen of modern Australian art history and professor of fine arts at the University of Sydney; Smith published a biography, Noel Counihan: Artist and Revolutionary (1993), and naturally gave him a significant place in his fundamental historical study, Australian Painting 1788-1960 (1962, updated in several later editions).

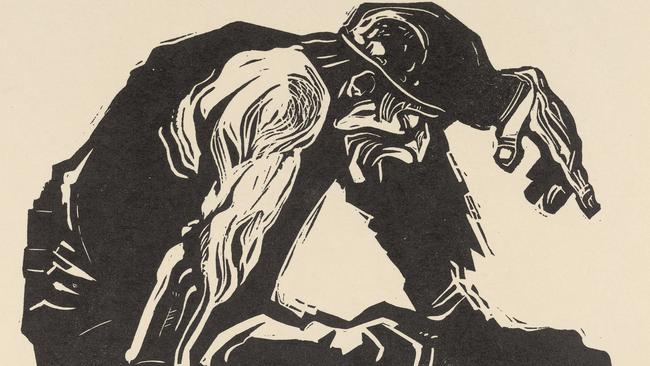

Counihan is best represented by his work in printmaking, the focus of the present exhibition at Geelong, and principally in linocut, which lends itself to dramatic emblems of suffering and forceful rhetoric in a medium that is literally black and white. Linocut is itself an easier and more accessible form of woodcut, appearing a little more than a century ago and soon adopted by modernist artists drawn to simplified images.

Both woodblock and linocut are relief prints, and the surfaces of the blocks, before they are cut by the artist, would print as an undifferentiated field of black; any area of white represents the cutting away of the surface of the block. Woodblock as a medium is thus given formal unity by the virtual blackness from which the image emerges, and such prints are often left with a black margin to remind us of the unifying shadow underlying the image. In modernist linocuts, however, artists frequently leave far greater areas of the print black for expressionistic effect and this is, as we can see in the present exhibition, an effect to which Counihan is drawn even more than many of his contemporaries and colleagues.

But if the images in this exhibition tend to be starkly black and white, so were the political views that lay behind them, and that have become increasingly alien and remote from contemporary political discourse. This was a time when loyal communists refused to recognise the murderous realities of the Stalinist regime and were willing to defend not only the gulags in Russia but also the invasion of Hungary in 1956 and of Czechoslovakia in 1968 – even though the events of 1968 in both Prague and Paris were, in hindsight, the beginning of the end for the communist model.

The left in those days still believed in class war, or at least in the struggle between social classes, as Karl Marx had described it, as one of the most important drivers of historical change. What they didn’t understand or manage to foresee was that “class struggle” would be transformed by the unexpected adaptability both of capitalist economies and of liberal democratic political systems. They didn’t realise the relations between the classes would be transformed by a combination of greater prosperity for the working class – making everyone a consumer – and the provision of social support by the modern welfare state.

Neither did they see that further developments in the consumer society and in a liberalised financial environment would still more fundamentally undermine the conceptual distinction between classes: on the one hand modern superannuation schemes – as well as home ownership – make everyone an owner of capital; and on the other hand the corporatisation of the workplace makes everyone a “worker”, even if some are paid vastly more than others. This is not to say that all problems of economic inequity have been resolved, but they can no longer be understood with the simplistic ideas of the old left.

Meanwhile, the new left – now facing an existential crisis in the US – gave up on class struggle and became infatuated with so-called identity politics. This is much more palatable and easier for the rich to embrace because they can achieve “justification”, as the born-again would say, without having to give up any of their real privilege, that is their wealth. As Bernie Sanders observed days after Donald Trump’s re-election, the Democratic Party has “increasingly … become a party of identity politics, rather than understanding that the vast majority of people in this country are working class. This trend of workers leaving the Democratic Party started with whites, and it has accelerated to Latinos and blacks”. Identity politics has proved a disaster, not just for the Democrats but also for the cause of social reform and tolerance because its zealots perversely overshot the point of social equilibrium and harmony.

It was a huge achievement to establish the principles of equal rights, equal opportunity and colour-blindness, as well as a similar indifference to other matters such as sex, sexuality and religion. It turned out that most people were open to the acceptance of others, even if they were different in some or all these ways. This was the true objective, to ensure everyone was accepted as a fellow human being in general, and specifically as a fellow citizen within the body politic.

Unfortunately, the identity zealots encouraged minority groups to continue thinking of themselves as minorities first, and of course as aggrieved minorities. Acceptance wasn’t enough; now “celebration” was demanded. And then as even this wasn’t enough, they were increasingly drawn towards more and more divisive categories of identity: for transsexual zealots, even feminists could be reactionary. And it wasn’t enough to accept transsexuals; this too had to be celebrated as though it were a victory over the implicit injustice of binary biology. In the final and possibly terminal phase of identity ideology, the magic word became “intersectionality”, where an individual enjoyed more than one minority identity. These became the true aristocrats of identity, naturally fostered by the compliant institutions of public culture.

All of this would have been completely incomprehensible to Counihan, who lived in a much more straightforward world of workers and capitalists, miners, dock labourers and impoverished mothers clasping their children. But this world did include a few ugly features that are still with us today. The first work in the exhibition is a linocut made when he was only 18: Tycoon (1931) reminds us that the typical left-wing caricature of a capitalist – with his top hat, tail coat and cigar – very often included what were considered distinctively Jewish features, and this certainly seems to be the case here. But the artist was young and immature, and undoubtedly changed his outlook when he had the opportunity to visit Auschwitz after the war, in 1949.

Meanwhile, some of his most memorable images were produced in The Miners, a series of six lino prints produced in 1947. The first three images are heavily defined in black against a white background and include two heads of young miners with helmets and headlamps, as well as one of his most memorable images, The Cough … Stone Dust, showing a miner sitting on the ground and supporting himself with one arm while he coughs up coal dust. Counihan, who had been treated for tuberculosis during the war, could no doubt sympathise with his suffering.

Still, there remains a question about the intended audience for these works, especially when we consider the exhibition’s title, A People’s Press. To what extent can one communicate with the people through what is still ultimately a fine art medium that will be purchased by those with money to spare? And after all, these images are still editioned in the normal commercial way: this print of The Cough is numbered in pencil, as is the convention with prints, as #36 out of an edition of 50.

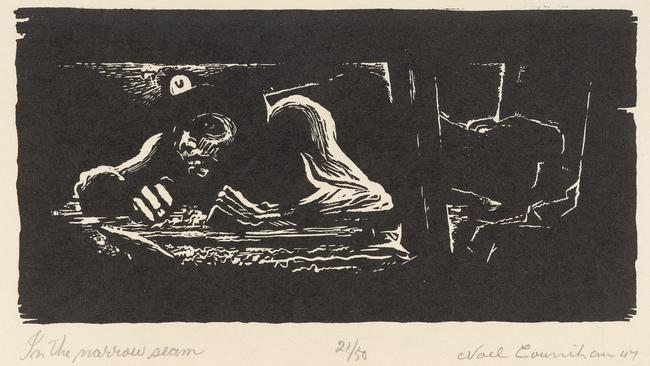

The remaining three in this series are designed with a black background, which means the image is defined by lines and patches of white that correspond to light striking a body in darkness. This is particularly appropriate in another of the artist’s best prints, In the Narrow Seam, where we see a miner crawling painfully through a tunnel only just high enough to let a thin man through; the intense feeling of claustrophobia is heightened by the darkness that impinges from all sides.

From the following year, 1948, there is a series of lithographs, a medium that allows for much more detail and subtlety, as for example in The Artist’s Mother, but does not achieve the same visual drama as the linocut. There is a classic class struggle image of three gaunt workers huddling in the darkness and talking to each other, perhaps apprehensively, as outside in the light we see the factory’s stout proprietor, in a three-piece suit, conferring with a manager or foreman in a lab coat. And there is another image of an unattractive middle-class couple with possibly obscene undertones.

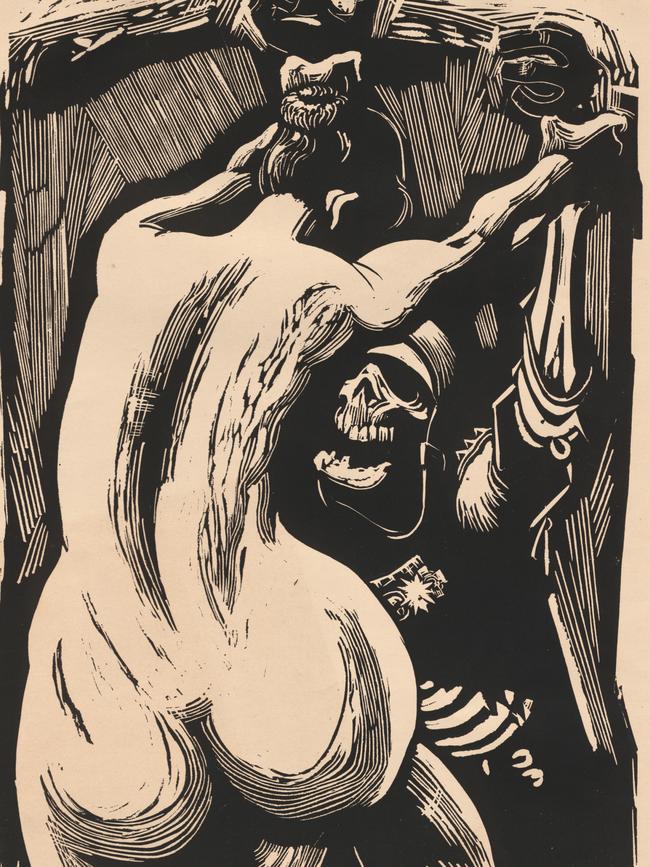

In 1949, Counihan attended a Soviet-run “peace” conference in Paris and after this made a couple of series devoted mainly to this theme, a folio of prints titled War or Peace? (1950), shown in a display case, and another series of six linocuts from 1959, in the first of which, Peace Means Life, a massive allegorical nude wrestles with a cadaverous figure of Death.

The last works are from a publication called The Broadsheet in the late 1960s (eight were produced altogether between 1967 and 1971); each sheet had a loose theme (Napalm Sunday, The Great Australian Summer, and so on) and a grid of prints and poems by various artists and writers. The latest one in the exhibition (1970) was given over to a single image by Counihan, appropriately enough, considering his interests and the events of the time, with the title A Time for Peace. But whether this rather weak image – even in a large edition (it is #699/1000) – convinced anyone not already in sympathy with its message is open to doubt.

Noel Counihan – A People’s Press

Geelong to 10 March

Noel Counihan – A People’s Press

Geelong to 10 March

National Gallery of Victoria

National Gallery of Victoria

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout