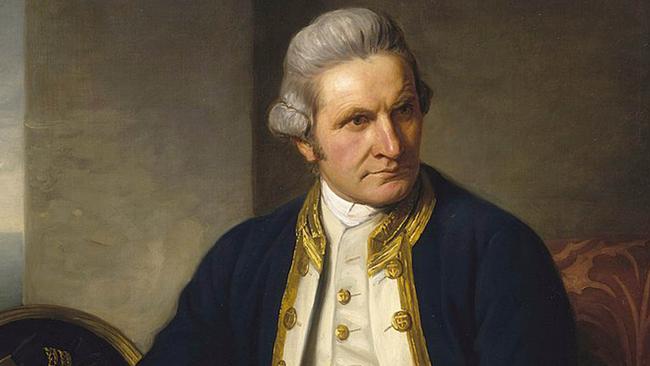

Captain Cook a giant of the science of his day and a humane and prudent man

A giant of the science of his day, a book sheds new light on Captain Cook’s remarkable forbearance even in the face of intolerable provocation.

At the very beginning of March it was announced that four Aboriginal fishing spears collected by Captain Cook on his visit to Botany Bay in 1770, donated to Trinity College at Cambridge in 1771 and held since 1914 at the Cambridge Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, were to be returned to a group descended from the tribe that occupied the area more than 250 years ago.

How this was reported was interesting. The BBC had, as usual, a fairly reliable account, although it implicitly refers to Cook and his party as “the first colonialists”, when of course they were nothing of the sort. Cook was an explorer, and established no colony or permanent base in Australia; the first settlement was not until almost two decades later, 1788.

The article quotes a member of the Aboriginal group as claiming the local people have a “deep, spiritual connection” with the spears, which are “part of a dreaming story that tells us how our people came to be”, though they are obviously and primarily practical implements used for spearing fish.

The ABC’s coverage was also balanced, noting – as mentioned in passing by the BBC – that these were the first Aboriginal artefacts ever collected by Europeans, or at any rate the earliest ones that remain extant today. The Guardian Australia unfortunately ran the headline “spears stolen by Captain Cook”, which rather disqualifies anything else they might have to say, while the Spectator Australia had a more substantial essay – in fact the only substantial discussion of the subject so far – by the distinguished historian David Abulafia (author of The Great Sea, 2011) arguing the case for retaining them in Cambridge.

One thing that no one mentioned, as far as I can see, was that these spears only exist today because Cook collected them and Cambridge preserved them. Otherwise they would simply have been used until they were broken, discarded and replaced. This is true of most Indigenous artefacts in Australia, including weapons, implements and bark paintings: the only ones that survive from the past are those that were collected by Europeans.

It may seem a surprising fact, but such is the norm in cultures that have no permanent buildings and therefore nowhere to store anything, and which also have no need to keep or preserve artefacts since they are constantly being remade and replaced. As they are, moreover, being replaced by identical artefacts, there is no need to save past ones as examples of an earlier technology.

All of that changes, however, with the disruption caused by settlement. The stable and ultra-conservative process by which each generation repeats the lives of the previous age and each artefact is replaced with an almost exact replica of the old ones is perturbed, traditions are confused, social roles are undermined and traditional skills are no longer passed on. Today European museums hold many objects that have not been made for generations, and which would be completely unknown if they had not been preserved by modern anthropology. This was recognised by Indigenous elders on the occasion of the National Museum’s Encounters exhibition of Aboriginal items on loan from the British Museum in 2015-16.

In any case, the confrontation at Botany Bay itself was fairly slighton both sides. The Aboriginals seem to have believed that Cook’s ships were vessels filled with dead souls, and were understandably terrified. The British fired to dispel those who were threatening them, but with deliberately non-lethal shot, and no-one was seriously hurt on either side. Cook was later to encounter far more savage behaviour from the Maori in New Zealand.

It is this context that Christopher Heathcote’s new book, The Compassion of Captain Cook – building on an essay published in Quadrant two years ago (June 2021) – sheds new light on Cook’s remarkable forbearance. The Indigenous people were, after all, neither enemies nor subjects, but autonomous populations with whom mutual trust had to be established.

Such was also the spirit of the instructions that Cook had received from the Admiralty in regard to the treatment of native peoples, which are quoted in full on p. 25, and include the following injunction: “to endeavour, by all proper means to cultivate a friendship with them… shewing them every Civility and Regard…” Further instructions from the Royal Society (quoted on p. 26) go even further, insisting: “shedding the blood of those people is a crime of the highest nature. They are human creatures, the work of the same omnipotent Author, under his care with the most polished European…”

This is the true Enlightenment spirit, more universal and rational than the theories of the Noble Savage which tended, at the same time, to romanticise native peoples, and far removed from the racist ideologies which only took root much later, partly as a perverse consequence of scientific advances in the theories of natural selection and later modern genetics.

Heathcote is particularly interested in a series of events that occurred while Cook was in New Zealand on his second and third voyages to the South Seas. In December 1773, Cook’s second ship, The Adventure, commanded by Commander Tobias Furneaux, was anchored in Queen Charlotte Sound in New Zealand for repairs. On the last day of the stay, Furneaux sent a party of men to forage for fresh food, led by Midshipman James Rowe.

When they did not return, Furneaux sent out a search party commanded by Lieutenant James Burney and including 10 marines. He discovered that Rowe and his men had been massacred, their bodies cut up and cooked, and the flesh divided among various groups, one of which they found still in the act of eating the flesh of their companions. After driving them off, they discovered more cooked body parts bundled up, perhaps to be taken to another community.

Shaken by this horrifying discovery, Furneaux took no further measures against the Maori but ended his mission prematurely and sailed home. Cook put in at Queen Charlotte’s Sound in 1774 and learned only enough to make him worried about the safety of The Adventure. A few months later he had confirmation from a Dutch ship about a massacre in New Zealand, and then learned of another cannibal killing involving a French vessel in 1772. Meanwhile stories of barbaric cannibals were causing a sensation back in London and in Europe more generally.

It was when Cook returned to Queen Charlotte Sound on his third voyage, in February 1777, that the question of what action to take with the murderers of his crew arose. Cook made it clear that no reprisals would be carried out and gradually discovered more details about the circumstances which had led to the massacre.

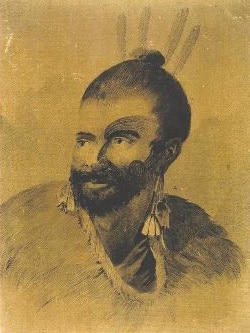

Finally, however, a Maori chief named Kahura came to see Cook on 24 February. By now Cook knew that he had been the leader of the massacre and had personally killed Midshipman Rowe. He was also disliked by many other tribal leaders, possibly because he had been involved in another inter-tribal massacre and cannibalism incident since Cook’s last visit. Even his interpreter, the young Tahitian Omai who had gone back to London with Furneaux and who was now returning to his homeland with the third voyage, urged Cook to have Kahura put to death.

But Cook once again showed extraordinary forbearance – possibly even, as Heathcote notes, at the cost of losing some credibility with the other Maori, who would have expected such a crime to be harshly punished, and who could have taken his clemency for weakness.

Not only did Cook assure Kahura of his safety, but he sealed the reconciliation with the remarkable gesture of inviting the native chief to sit for his portrait, which was executed by John Webber and is today in the Dixon Collection of the State Library of NSW. And thus Heathcote has restored the remarkable story behind what might otherwise be passed over as simply another one of the many pieces of art documenting Cook’s voyages.

In a further section of the book, however, Heathcote uses his close study of the primary sources for these events to reveal how easily populist writers and even academic historians can cut corners, conflate events, concertina chronologies and simply misquote their sources – sometimes relying on other secondary sources in what can become an increasingly misleading sequence of Chinese whispers.

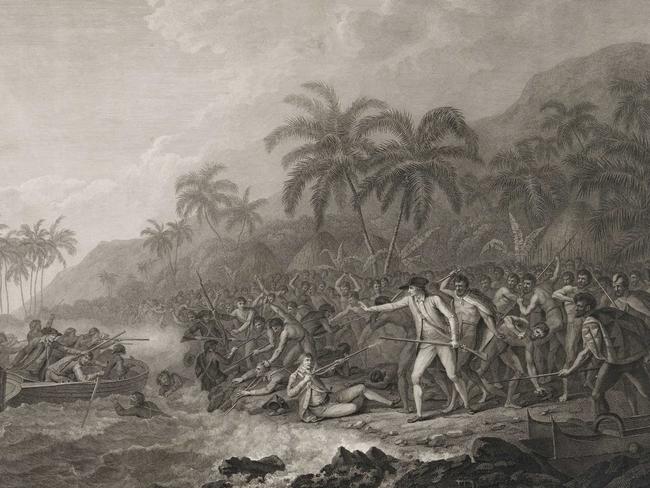

One of these cases is the story of the trial of the cannibal dog, which gave its picturesque title to a book, Anne Salmond’s The Trial of the Cannibal Dog (2004). The facts seem to be that some young midshipmen held a mock trial for a dog acquired from the Maori, killed it and ate it. This was presented in Salmond’s book, and since then cited by others, as having taken place on another of Cook’s ships, Discovery, at the same time as the meeting with Kahura, as an act of protest against his clemency that verged on insubordination. Heathcote shows that this interpretation was based on a careless reading of the sources and that the “trial” probably happened months later and possibly even after Cook’s murder in the other massacre mentioned in the book, that took place in Hawaii on 14 February 1779.

The other question was what exactly happened when Lieutenant Burney, with his party of marines, discovered evidence of the massacre and encountered the group of cannibals in December 1773. It is certain that he ordered his marines to fire shots to disperse the group, but what weapons and ammunition were used and whether the intention was to kill or merely to inspire fear is much less clear.

Once again Heathcote reveals a pattern of historians repeating or ratcheting up the accounts of previous authors, while failing to look closely at the primary evidence. Thus the most sensationalist accounts imply that a considerable number of the Maori must have been shot, which is not supported by the primary sources. Kahura himself boasted to Cook that none of his people had been hurt in the attack.

There is much more in this short and closely-researched book, but one of its main lessons is the value of a rigorous reading and collation of primary sources, rather than relying on and repeating the conclusions of others. But above all the book reminds us that, in spite of current prejudices, James Cook was not only a great mariner and cartographer, and a giant of the science of his day, but a good, humane and prudent man.

The Compassion of Captain Cook by Christopher Heathcote (Connor Court Publishing, 2023).

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout