William Bligh was brilliant, but he was unfit to lead The Bounty

James Cook rated him highly and, crucially, Joseph Banks was a friend, but William Bligh’s flaws made him unfit to be captain of The Bounty.

Nothing about the Bounty or its famous mutiny is as it seems. Not least of which is its most famous participant: Fletcher Christian.

He has been played by Hollywood’s leading men for almost 90 years – Errol Flynn, Clark Gable, Marlon Brando and Mel Gibson. But in describing the real Fletcher Christian, even “nuggety” might be an exaggeration, not that there was ever a portrait of him in his lifetime.

His one-time boss, Captain William Bligh, filled in some gaps about the appearance of his “master’s mate”: “(He is aged) 24 years, 5 feet 9 inches high, blackish or very dark complexion, dark brown hair, strong made; a star tatowed (tattooed) on his left breast, tatowed on his backside; his knees stand a little out, and he may be called rather bow legged. He is subject to violent perspirations, and particularly in his hands, so that he soils any thing he handles.” And that before the pair fell out. But neither was Bligh an oil painting, notwithstanding that many of him were completed in his lifetime for which, one assumes, he formally sat.

Harrison Christian, a descendant of Fletcher Christian, and the author of Men Without Country, an account of the politics behind the Bounty’s notorious journey, describes Bligh as being just “five feet tall with jet black hair and a distinctive pallor that never changed in the tropics”. He describes his ancestor’s nemesis’s face as “small and pixie-like, with a dimpled chin and a noticeable boyhood scar across one of his cheeks”.

The author explains that the personality that attended these regrettable features was also unfixably flawed. Highly skilled at navigation and mapping, few people describe Bligh as other than a self-pitying, self-indulgent, greedy, vain, thin-skinned, manipulative on-the-spectrum bully.

And complain? Bligh may have been the original Pommy whinger. His captain’s diary was strategically light on details of the fractious life aboard the Bounty’s unsettled trip, but in letters to friends and relatives he didn’t hold back about the conditions, his disdainful treatment by the Admiralty, and the incompetent men by whom he insisted he was surrounded.

In any case, the Bounty’s journey to the other side of the Earth – the mutiny, the deaths, the dishonour, the court martial, the hangings – were all a complete waste of time. The mutiny that has transfixed filmmakers, poets, authors and musicians for more than 200 years took place on April 28, 1789. It was 1792 before anyone realised that first journey had been as pointless as its follow-up, also captained by Bligh, during which, unchastened by the events on the Bounty, the spiteful Bligh behaved as he always had.

Often the Admiralty appointed men to its ships based on class and favour: Bligh had recently married into an influential family while in his corner was the king’s friend, Sir Joseph Banks, who would later secure Bligh the role as governor of NSW. He was probably unfit for either post.

Among the enemies he made second time around was Matthew Flinders, who was belittled by Bligh for his cartography, but went on to be first to circumnavigate Australia – he also named our continent – and be acclaimed as a great mariner. Another crew member, Henry Smith, whom Bligh humiliated and reduced to the rank of seaman, jumped overboard and drowned rather than endure the abuse. Few sailors of the age could swim.

Bligh’s second-in-command, Francis Bond, wrote in a never-sent letter that his captain had “treated me (nay all on board) with … insolence and arrogance”, and referred to Bligh’s “ungovernable temper”. Bligh, he said, “longed to flog the whole company”, lashings and sometimes hangings being the Royal Navy’s currency to secure compliant behaviour on long voyages from England. There was nothing like the hooded, lifeless body of a colleague dangling from the yardarm to help keep the peace.

In any case, to guarantee the success of the Providence’s journey with its noxious captain, 20 marines had been sent. There’d be no second mutiny. And there’d be no first prize. The Bounty’s mission was to sail to Tahiti to pick up breadfruit (ripened, seeds and cuttings – all up, Bligh’s team gathered 1015 plants) to take to the West Indies to feed enslaved Africans working the British sugar plantations whose diet consisted of corn and the starchy plantains that had come from the revolutionary American colonies suddenly no longer allied to Britain. The mutiny curtailed that mission, but the dogged Bligh was back three years later, finally coming through with the breadfruit.

The Bounty’s legend resonates today, and it is not one tale, but several. There is the challenging outward journey where, departing late because of the Admiralty’s administrative inertia, the Bounty struggles to round Cape Horn as huge seas and inexhaustible winds push the little, refitted merchant vessel back, as Bligh thought they might that late in the season. Huge waves caved in the stern windows and, as Harrison Christian records, seven hogsheads of beer (240 litres each) are swept overboard while casks of rum rupture and empty, bad omens for superstitious sailors. Frustrated, Bligh turns the Bounty and heads for the cape at the other end of the world.

Not for the first time might Bligh have sniffed rum and rebellion. He’d been sailing master on James Cook’s third Pacific voyage and the captain thought highly of him, and Bligh would get his crew safely to Tahiti. But, Harrison Christian writes, there were various frictions on board by then and the men were relieved by the relaxed utopia of the island on which they stayed almost six months.

Three men deserted the Bounty here, and were found, returned to the ship, and spent a month in irons before being flogged twice. Then the ship’s shore line was cut. When Fletcher Christian returned to the Bounty having failed to collect water after being challenged by locals, Bligh accused him publicly of cowardice. Their relationship was irrecoverable.

Bligh was also purser on the journey and hoped that by being parsimonious with food and supplies, he could cash them back in England. Harrison Christian reports that his stinginess with food lost him the support of the crew. A mutiny was inevitable.

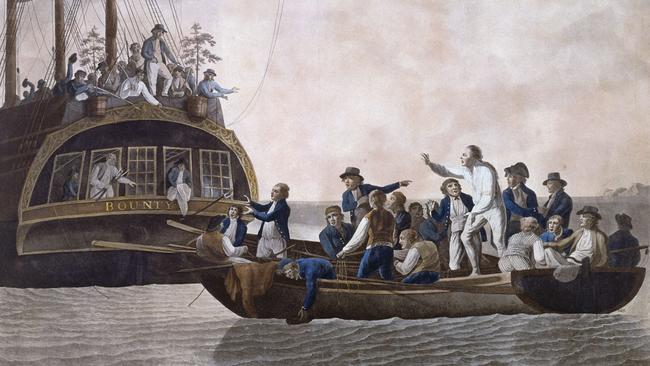

When Christian forced his way into Bligh’s cabin he announced: “Bligh, you are my prisoner.” Soon Bligh was adrift with 18 other loyalists in a 7m launch meant for 10. They might reach Tofua in Tonga, Christian must have thought to himself. But Bligh navigated the boat to East Timor, 6071km away, in 47 days.

“He was a brilliant man, you could even call him a genius – (with) his talent and aptitude for navigation,” Harrison Christian told me from his San Francisco home. “(But) he was not a leader of men and he had this habit throughout his life of rubbing people the wrong way … He enjoyed humiliating people.”

Meanwhile, Fletcher Christian and his crew, using Bligh’s maps, sailed first to Tubuai – Bligh had charted it 12 years earlier – then to Tahiti, where 16 men opted to stay. Christian, eight mutineers, six Tahitian men, twice as many women, and a child (Harrison’s five times great grandmother), then headed off to find Pitcairn, the ends of the Earth where surely even His Majesty’s navy would not find them. By the time anyone did 18 years later, a sole mutineer, Alexander Smith, survived. The others died or had been killed in scenes prefiguring William Golding’s Lord of the Flies.

“I took the title from a Lord Byron poem about the mutineers, Harrison Christian explains. “It describes the isolation of the mutineers and their statelessness. Their only link to civilisation – the Bounty (which was burned) – is gone.”

He believes Bligh was driven to return to England and tell his version of events. “He had a keen sense to control the story … to acquit himself well. Maybe he got some of that sense from his voyage with Cook because when Cook was murdered there was a lot of squabbling among his crew, and finger pointing and officers of the ship blaming each other for Cook’s death.”

As Harrison Christian writes it, Bligh was inspired by Cook and the manner in which he cared for sailors, kept scurvy at bay and was less violent to his men. Bligh had idealistically vowed that on his Bounty voyage his ambition was to whip no one. He did flog crew, but never as many as Cook.

Two years after survivor Smith died (his real name had been John Adams and Pitcairn’s “capital” is called Adamstown), the Pitcairn islanders felt they might soon be too populous for their dot in the Pacific and the British government transported them to Tahiti. Many found their old home too corrupted by the influence of the Europeans, whose ships had never stopped arriving. Unable to adapt, most soon asked to return. Soon crowding themselves out again, they sought a new home and Queen Victoria invited them to live on the decommissioned penal colony of Norfolk Island, 1600km northeast of Sydney. A total of 163 Pitcairners turned up there on June 8, 1856. The following year 16 returned to Pitcairn, and 27 followed five year later. At last count it had 67 inhabitants.

Harrison Christian, who was born in Auckland to where so many of the Norfolk Island families have migrated, has never been to Pitcairn, but he has twice been to Norfolk, whose phone book includes so many Christians they are often listed by their nicknames.

He wrote the book while locked down in California last year. “It was always part of my story. My grandfather came over from Norfolk Island and settled in Auckland … I saw all the books and movies as I was growing up. There is a feeling of pride and specialness.”

Men Without Country (Ultimo Press) is out now.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout