Bruce Munro’s show at Heide could be just what we need

Smartphone have had a devastating effect on the mental health of individuals. This meditative exhibition could be the antidote to modern life.

It is hardly surprising that our time has produced an avalanche of books on mindfulness, meditation and simple presence, for no age has been more distracted and disoriented. Humans have of course always been prone to passions and thoughtless impulses, but in a functioning culture these instincts are mitigated by convention, custom and law.

This system of direction and inhibition has been eroded with the accelerating breakdown of culture and belief over the past century. Culture is a system for maintaining sanity, but the mass media that largely shapes the thinking of modern consumers – systematically generating unhappiness and a sense of lack – is a mechanism for producing neurosis, becoming more pernicious still with the development of the internet and subsequently the smartphone.

In only 15 years, the new social media enabled by the smartphone have had a devastating effect on the social fabric of modern nations and on the mental health of individuals. All of this was aggravated by the Covid lockdowns which forced people to spend even more time on such media. Apart from the immediately obvious echo-chamber effect, in which consumers are surrounded by relentless confirmation of their own prejudices, social media has become a field for massive and systematic manipulation of mass opinion, including by the agencies of hostile foreign states.

At the individual level, we have witnessed an epidemic of mental illness in young people, as well as many recently publicised outbreaks of collective bad behaviour. Today’s guardians of public morality seem surprised: how can this be happening at the very time when standards of acceptable behaviour and speech are ostensibly becoming ever more restrictive and prescriptive? But, of course, such constraints only make the problem worse.

If anything, mere rules and prohibitions are an invitation to transgression, especially for rebellious young people. The guardians of morality can cancel books and even people within their own bubble, but as we saw in a recent ugly outburst on a radio talk show, the mass mind is immune to cancellation. All that is achieved by cancellation is to destroy the space for liberal and open discussion, leaving the pious to engage in self-congratulation while the masses seethe in a swamp of vociferous and vacuous opinion.

What prevents really bad behaviour is a combination of deep cultural norms and standards instilled from earliest childhood, with a humane and generous attitude taught by example, including by parents and teachers. But today these beneficial forces are often drowned out by other voices – of peers or of malign influences – amplified by the new media.

Silence, stillness and presence are antidotes to the constant and mostly pernicious noise that surrounds us. Practices like yoga and meditation, simply by allowing the mind to find quietness, give it relief from the inner chatter it generates, as well as from the intrusion of external voices. Unfortunately, these are seldom taught at school, where physical education programs do little to contribute to longer-term wellbeing and sanity.

Although we tend to associate disciplines of the mind with the East, they have deep roots in the Western tradition as well, especially from the Hellenistic period, when the old polis system gave way to larger empires in which the place of the individual was much less clearly defined than it had been. Both Stoicism and Epicureanism, although starting from different premises, sought to achieve and maintain peace of mind in the face of the vicissitudes of this world.

Their conclusions, about renouncing desire and fear, about acceptance and non-resistance, and about living in the present moment – in many ways consistent with Buddhist ideas – are explicitly discussed by such authors as Epictetus, Lucretius, Seneca and Marcus Aurelius, but also pervade the poetry of Horace and others. And these ideas were important again in the early modern period.

This tradition of classical wisdom was, however, criticised by mid-17th century authors such as Pascal and La Rochefoucauld, and seems to have lost ground in the 18th and early 19th centuries, when quietistic attitudes were less appealing; but then Europe began to rediscover oriental wisdom, from the rise of Sanskrit studies in British India to Schopenhauer’s interest in Buddhism and Nietzsche’s re-imagining of the Persian prophet Zoroaster in Thus Spoke Zarathustra (1887).

By the end of the 19th century, especially under the influence of Theosophy, important oriental texts were rediscovered, from the Yoga Sutras to the Tibetan Book of the Dead. Christianity was in decline, the modern world was increasingly materialistic, and there was a longing for alternative sources of spirituality.

This is the process that accelerated in the second half of last century, from the time of the 1960s counter-culture, when everything eastern, including yoga and meditation, became more broadly popular. And today, characteristically, these traditions have proliferated into sometimes incongruous hybrids, assimilated by consumer culture as products and services, and tacked on to lives dominated by desire and distraction.

One modern representative of the fascination with the East, following in the footsteps both of Schopenhauer and of Nietzsche and influenced by Theosophy, was Hermann Hesse in his novel Siddhartha (1922) – another work of 20th-century literature whose centenary we celebrate this year. The protagonist of this novel is a young man who is a contemporary of the historic Gautama Buddha (who also shared the name Siddhartha), and whose life and quests intersects with those of the great teacher.

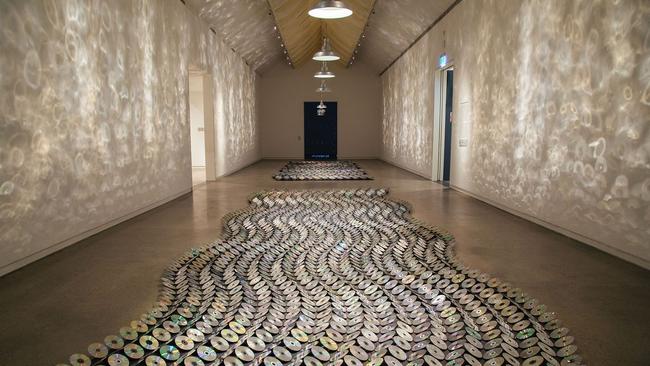

Siddhartha’s experience of crossing a river with the help of a ferryman is the basis of the largest interior piece in the Heide survey of Bruce Munro’s work. The theme of crossing the river is ancient and highly symbolic; it is represented frequently in myth – as in the river crossings of Heracles and Deianira, or that of Jason and the old woman who turns out to be Hera in disguise. Philosophically, the river was taken by Heraclitus as an image of the constant flux and change to which all beings are subject.

Munro’s river is made out of old CDs, mounted at angles like choppy water, in a broad undulation that fills the central space at Heide, interrupted by a passage through which the audience crosses.

The river is illuminated by overhead lights that flash in what seems at first to be a random sequence; in reality, as we are told, they are flashing in morse code and the text they are signalling is a passage from Hesse’s novel, in which the boatman reflects on the meaning of the river.

The most poetic aspect of this work is the complex and constantly changing play of light reflected from the discs onto the walls of the gallery in a cloud of overlapping circles. The effect is subtler and more beguiling in what is perhaps the most successful work in the exhibition, a smaller version of the river subject in an adjacent gallery.

Here, light in the visible patterns of lines of morse code is projected in a rolling sequence over an oblong of reflective metal on the floor. The border of this oblong has pyramidal nobs at intervals which reflect the changing flow of light, but more sparingly, so that fainter and more scattered wisps of light appear all over the walls like stars, and some light even reflects onto the floor, like a kind of accidental spillage.

Also appealing is another room with four circular projections on the floor.

These are in fact a series of formally similar works projected one after another: all variations on a circular mandala shape that evokes the practice of meditation – patterns arise in the centre, expand, and open out like flowers – while some of the soundtrack consists of mantras used during meditation.

Less successful than these are several works where Munro has started with photographs of places, but then broken them up into the colours of which they are formed and rearranged these colours. In one room, rows of colour tiles occupy one wall, while the facing one is a digital grid in which the colour tiles form themselves into different configurations.

Another set of work based on the same principles arranges tiny dots of colour into spirals, or in one case a double spiral. On the whole, though, this work reminds one of so-called molecular cuisine where chefs go to great lengths to deconstruct fruit and other substances into froths, when they might in fact be tastier, more nutritious and above all more appealing in their natural state.

Munro’s work is something of a puzzle. We cannot but sympathise with his aspiration to silence, quietness and meditative attention. And yet it often seems that he is thinking too hard and not feeling simply and intuitively enough. The idea of morse code, for example, is very interesting, but no one is really going to have any idea that the lights over the river are flashing in morse code without being told, and that rather defeats the point.

The smaller work mentioned earlier is more successful both because the morse code appears in visual form, so that we don’t need to be told, and also because the poetic effect of the light flecking the walls is effective even if we don’t know what else the work is intended to mean. The universal and fundamental rule, however, is that art has to convey meaning directly and in its own form; it cannot be unintelligible without reading the label.

At the same time, one has to ask what the point is of using CDs. Yes, they are useful reflective surfaces, but we have to account for their meaning as artefacts. These are essentially data storage devices. Can we see the river as made of now-obsolete data? Can we try to feel that it stands for all the vast amount of useless data that has now become mere hubbub? But do we really feel that?

The question, then, is not only whether ideas are adequately transformed into aesthetic experience, but also whether materials are fully assimilated and integrated so that they contribute to meaning and don’t end up confusing the viewer instead. One could think, in contrast, of the work of Chiharu Shiota, discussed here recently, where all materials are completely assimilated into the aesthetic vision.

It is a pity I couldn’t stay to see the work that Munro made especially for this exhibition, but which can only be appreciated when lit up at night. I did walk down into the gardens to see it in its non-illuminated state and I imagine it must look delightful when lit up.

When seen in daylight, the most appealing aspect of the piece was the design of the hundreds of tiny stalks that surround the main illuminated disks. From these sprout optical threads with little baubles on the end. These filaments were blowing in the breeze, and no doubt greatly contribute to the animation of the whole installation in the dark.

Bruce Munro: From Sunrise Road, Heide Museum of Art, Melbourne, until October 16.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout