Billy Corgan on wrestling, trauma and 35 years of The Smashing Pumpkins

The Smashing Pumpkins’ combative frontman grapples with nostalgia, trauma and 35 years helming one of the most influential alt-rock bands ahead of his wild new show melding music with professional wrestling.

If there is one thing the towering frontman of The Smashing Pumpkins has rarely been during his three decades in public view, it’s unavailable.

His band wielded a dynamic, diverse and unique sound that had become massively popular in a MTV-driven culture where alternative rock reigned supreme, and unlike many singer-songwriters of his era, Chicago native Billy Corgan has long worn his artistic grandiosity and endless confidence on his sleeve – right alongside his transparent insecurities – as he filled reporters’ notebooks and recorders with reams of quality material.

Millions flocked to a combustible, uncompromising sound that appealed to young men and women in equal measure. Corgan possessed a rasping, nasal vocal style that tended to attract or repel listeners instantly; you were either a fan of the singer’s distinctive delivery or you weren’t, with little middle ground to be found.

In stark contrast with peers such as Kurt Cobain and Eddie Vedder – Corgan’s fellow generation-defining vocalists in Nirvana and Pearl Jam, respectively, who both wrestled mightily with the mind-blowing transformation of suddenly being seen as totemic, culture-shaping icons – the head Pumpkin made a habit of speaking his mind whenever a hot microphone was nearby.

Articulate and combative, Corgan suffered no fools, and pushed back against perceived falsehoods wherever possible, while otherwise seeming to enjoy the sport of being in the spotlight.

This was a man who was self-aware enough to admit that, as a child, he wanted nothing more than to be a famous rock star. Against the odds, he then became a famous rock star, and fully embraced all of the ridiculousness that inevitably follows such a rise.

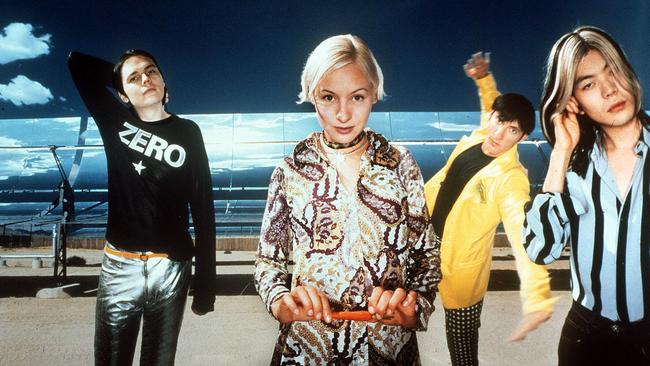

He reliably gave good interview, as we say in the journalism trade, so much so that his co-founding bandmates – drummer Jimmy Chamberlin, guitarist James Iha and bassist D’arcy Wretzky – were known almost entirely for their musicianship, and little else besides, other than brooding as one at the camera in press shots from that era. Yet the voices of those players were rarely heard, as the three other Pumpkins ceded the burden of public relations to the frontman.

So plenty of people came to think of the band as something akin to the Billy Corgan Experience, which the singer-songwriter – a committed megalomaniac with a stronger work ethic than just about any individual in popular music – probably didn’t mind so much.

For his part, Corgan took the role of sole mouthpiece in his stride – particularly once he began playing “the heel”, a term from the sport of professional wrestling, where a character is written as deliberately provocative and unlikeable.

Asked when he began actively playing the heel, Corgan tells Review with a laugh: “About ‘92.”

“You reach a point where you’re so into absurdity, you cause cognitive dissonance,” he says. “So I’m standing there in a shirt that says ‘ZERO’, my head is shaved, and I’m wearing silver leather pants, I’m playing three-hour shows, the name of my band is The Smashing Pumpkins — and I go into an interview and they’re like, ‘How the f..k did you get here?’ And I’m like, ‘Well, you tell me.’ It would need this weird qualification thing of, ‘Did you ride around in a van long enough? Did you pay your dues? Are you authentic?’”

Some of his rock star peers landed on public personas that were plainly good for business: he gives the offhand example of “the car mechanic with the bandana in their pocket”, an evocative phrase that probably conjures the image of at least one US singer-songwriter right away. Corgan, ever the outsider in his own mind, went the other way by choosing a persona that was combative. The sight of the Pumpkins frontman wearing a black long-sleeved shirt stating ZERO in a bold silver font, above a silver star, is one of the defining images of the 1990s alt-rock era.

That black shirt was introduced in the music video for the incendiary 1995 hit Bullet With Butterfly Wings, which began with an unforgettable lyric: “The world is a vampire …” This also marked one of Corgan’s last public appearances with hair; soon after, he adopted the character in the video for the 1996 single Zero, which was led by a buzz saw guitar riff sparkling with harmonics.

“Everybody around me said, ‘This is bad for business’, and I said, ‘Well, this is going to be my way of navigating it’,” he tells Review. “Because whether I was seven years old, or 17, or 27, they continually told me, ‘You are not welcome’.

“So I inverted it and I went into surrealist absurdity which is like, ‘Oh, you think I’m a nobody? I’m gonna really be a nobody’,” he says. “I mean, what screams ‘nobody’ more than shaving your head and wearing a shirt that says ZERO in 1995, when everybody else is running the opposite direction, and talking about how earnest they are, how much they care and how real they are?”

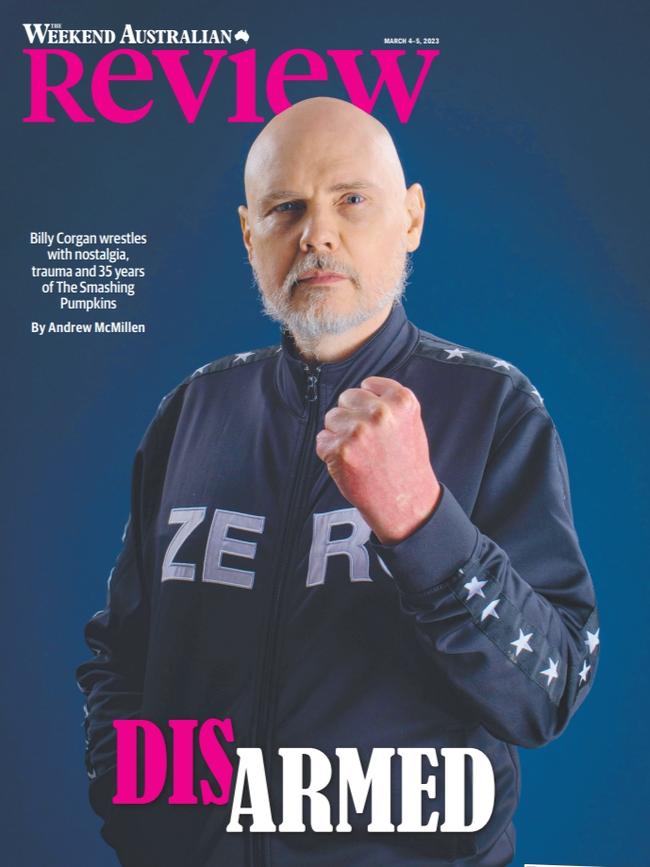

The image of Corgan-as-Zero is one that adorned the music magazine covers of yesteryear, but it has proved strangely indelible, too: today on the social media platform Instagram, his biography contains those same four capital letters, and his profile picture is of himself – now 55, still bald – wearing a zip-up black ZERO hoodie while holding up a raised fist.

Reminded that this particular persona resulted in a great many people around the world rushing to the merchandise desk at Pumpkins concerts, Corgan laughs and says, “Well, that’s the great trick. Think about it: our largest-selling shirt, and probably my greatest graphic creation doesn’t even say the band’s f..king name!”

When Review connects with Corgan on a video call in late February, he is lounging in the bedroom of his 1920s estate home in Illinois; soon, The Smashing Pumpkins will tour Australia for the first time since 2015.

As well, the band is partway through issuing ATUM, its 12th album. Pronounced “autumn”, it’s a 33-song “rock opera” with a weighty sci-fi concept that’s being released in three parts, with the final chapter to be completed in May.

Unusually for a man who has had an uncomfortable relationship with his past, the tour – which also features fellow US alt-rock veterans Jane’s Addiction – shares its name with one of his most famous lyrics, penned circa 1995. Was this decision a case of the band trying to satisfy themselves with new work, while also acknowledging one of the songs that plenty of people hope they include in the nightly set list?

“No,” he replies. “For me, the best place to be spiritually is in full acceptance of the past, in full openness towards the future, and fully present in the present. So when we talk about our past, we have no fear. I encounter those people at airports who think I haven’t done anything good since 1993. I’m long past worrying about that.

“The Pumpkins has always worked with absurdity,” he says, smiling. “When we name a tour ‘The World is a Vampire’, we’re in full recognition of the metadata of the thing – because, as I walk through the airport, it’s like, ‘It’s the ‘rat in the cage’ guy! It’s Bozo the Clown! He’s wearing the big shoes, and his head still is shaven!’ To one guy, I’m the ‘rat in the cage’ guy; it’s all good.”

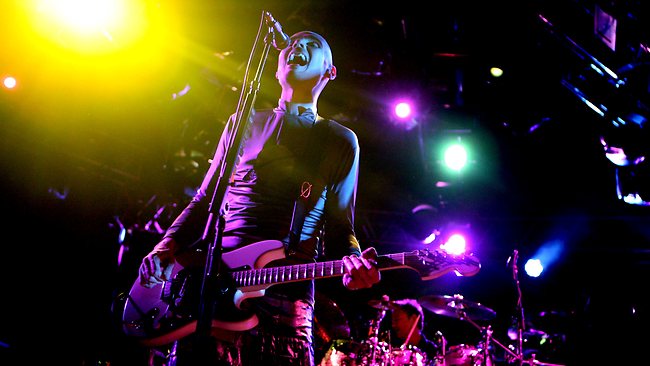

When Corgan encounters those characters, they’re usually thankful for the role his music played in their lives, even if they haven’t followed his more recent material. With his three bandmates, he developed a style of alternative rock that traversed the spectrum from serene to scabrous, from emotive melodicism to concussive explosivity, often within the space of a single song.

Its 1991 debut album Gish – produced by Butch Vig, whose next gig was producing Nirvana’s Nevermind – laid a compelling artistic blueprint that was later finessed on two mega-selling albums in Siamese Dream (1993), then double-album Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness (1995), a 28-song set that marked the apex of the band’s popularity, productivity and prominence in pop culture.

In full flight, few acts could match the sheer wattage that the Smashing Pumpkins emanated from the world’s stages. It helped that, in Chamberlin, the group possessed a powerful and innovative drummer; the twin-guitar attack of Corgan and Iha, meanwhile, regularly summoned a wash of beautiful, scorching noise whose lead lines and rhythmic chords meshed perfectly.

(Various personnel changes meant that, at times, Corgan was the only original member alongside hired hands; Chamberlin and Iha returned to the fold in 2015 and 2018, respectively, while Wretzky has lived a Pumpkins-less life since 1999. Guitarist and keyboardist Jeff Schroeder has been at Corgan’s side since 2006, while Jack Bates – the son of Joy Division and New Order co-founder Peter Hook – has played bass at live shows since 2015.)

The upcoming Australian tour name, meanwhile, does have the scent of a marketing idea cooked up by a promoter looking to shift as many nostalgia-laced tickets as possible, rather than by the band – yet on this count Corgan is quick to dispel my misconception.

“It was my idea,” he says. “It’s my line, you know? I don’t see it as nostalgic at all. I think it’s more like saying, ‘Calling a movie Spider-Man 7 is nostalgic.’ No – it’s our f..king shit. It’s endured. If you know anything about the band and don’t see the absurdity in calling a tour ‘The World is a Vampire’, then you don’t know us at all.

“I mean, the name of the band is a piss-take,” he says, smile growing. “Think about it: in one of our biggest songs, I literally open the song by saying, ‘The world is a vampire.’ It’s such a crazy, dumb line – so it’s a crazy, dumb tour. I understand what you’re saying, and there’s no sensitivity to it; it’s more the quasi-version of, ‘Who gives a shit?’ It’s kind of funny to us.”

Born William Patrick Corgan in 1967, with a large, red birthmark running up one arm, his upbringing was far from idyllic. He was forced to learn early about social isolation and independence, as his life was tarnished by neglect. His father was a heroin-addicted blues guitarist; his mother had a mental breakdown and abandoned him when he was four.

The oldest of four boys, he became the de facto guardian of a younger brother born with mild cerebral palsy; his own care was passed between a range of family members, including an abusive stepmother. This childhood turmoil later appeared in his songwriting: in a single from Siamese Dream titled Disarm, amid strummed acoustic guitars, tolling bells and swelling strings, he sang: “Disarm you with a smile / And leave you like they left me here / To wither in denial / The bitterness of one who’s left alone / Oh, the years burn …”

Stability, unconditional love, kindness, familial affection – these were foreign concepts to a boy who soon became powered by a bottomless well of rage, coupled with an incessant desire to prove wrong everyone who ever doubted him.

Corgan began playing the electric guitar at 14, and threw himself at the task with a single-minded focus. Practising for hours every day, he immersed in the music of Black Sabbath, Queen, Cheap Trick and Van Halen, learning quickly.

“Everything’s always been a struggle for me, but for some reason, guitar just came really easy,” he tells Review, noting that, within six months, he shot from tuneless newbie to undeniable shredder. “The guitar players in my school treated me with suspicion, like I was cheating, or I’d done some deal with the devil.”

He hadn’t, but his disciplined persistence with that instrument became the songwriting engine that drove The Smashing Pumpkins, which formed in Chicago in 1988, when Corgan was 21.

His lacking home life meant that he attempted to create a new family within the band, but it, too, was dysfunctional: at times it seems the only thing linking the four of them was the music itself. Friendships were sidelined in their ascent, especially once fame, money and plentiful illicit drugs entered the equation.

Time doesn’t heal all wounds, but it generally helps people come to terms with their past. Asked what it means to be playing music with Chamberlin and Iha together again today, Corgan replies, “Once you’re back in the dynamic with two of the other three original members, you realise that the most important part is you’re watching the living result of a decision that was made many, many years before, and you have the full opportunity of examining the roots of that.

“It was me, James and Jimmy at my father’s house, where he was dealing drugs out the back door, circa 1988,” he says. “When you see us on stage in 2023, you can do your own math: you can go back to 1988 and see Jimmy with the mullet haircut, and me with the long, goth hair. You know what’s coming: the good and the bad.

“When you see it in present-day terms – whether it’s the lines on our face, or the way we interact – you have this opportunity to see where all that went. Obviously if you had all four, you would have the full opportunity of seeing the full insanity that was the original band – but I think with the three of us, certainly from the musical side of the equation, you’re seeing most of it.”

A lesser-known side of the head Pumpkin is that he’s mad for professional wrestling. In his home country, he has owned and operated the National Wrestling Alliance since 2017, having worked in that most American of show-businesses for more than a decade.

On the upcoming 10-date tour, Corgan will merge these two worlds of music and wrestling when his crew of performers takes on members of the Wrestling Alliance of Australia in the ring between sets, in what has become an unusual talking point for fans. “It’ll be presented in a very accessible way,” Corgan says.

Professional wrestling, he adds, is “fundamentally designed to be enticing – but because of its rap in culture, it tends to get disregarded as something ‘too lowbrow’. But people need to be reminded that it came out of the carnivals; it’s meant to be for everybody.”

Having long ago dropped the “heel” persona of yore, the singer-songwriter appears strikingly content with his station in life. Part of that comes from having spent a long time out of step with mainstream culture, as tastes and trends shifted.

In 1997, while working in a Hollywood Hills mansion on Adore, the fourth Smashing Pumpkins album, Corgan bookmarked the moment with characteristic honesty and self-awareness.

“I have achieved the greatest of success and tasted the stupidity of my own hubris,” he wrote in a LiveJournal entry published in 2005. “The old dreams are dead, and now my life becomes more a trudge of survival, and in some messed up way, as long as I keep working, I am OK.

“There is a part of me that does not want it to end, because I am afraid of what is waiting for me on the other side.”

That was a heady time, where despite peak inter-band dysfunction, Corgan would tinker with his equipment from midday to midnight, then spend the rest of the dark hours hanging out in a jacuzzi, taking downers or psilocybin mushrooms depending on his mood, shooting the shit with fellow A-list celebrities and watching the twinkling lights of Los Angeles spread out like jewels.

Since then, The Smashing Pumpkins have released seven more sets; its 12th album ATUM will be completed when its third chapter is released in May.

What waited on the other side in 1997 was a kind of commercial irrelevance. None of the albums the band has issued in the past 25 years has set the charts alight; most people haven’t heard any of those songs.

Strangely enough, he’s made peace with that. “When I was a nobody, I wanted to be a somebody – and when I became a somebody, it was about hanging on by your fingernails to maintain status,” Corgan says. “And then when you go through the inevitable kind of downturns in your musical life, you (begin thinking) ‘How will people perceive me?’

“Now, I’m past all of that, and it feels really nice, because I have my own relationship to my music life,” he says. “And so wherever anybody intersects with it – whether it was yesterday, or 15 years ago – I’m just very grateful, because you realise, particularly in such a complicated social/world culture, vis-a-vis the internet, that to have any connectivity to anybody is kind of shocking.”

On the day we speak, Corgan has posted to Instagram a photograph of himself with his two young children, Augustus and Clementine, at Walt Disney World in Florida, where they’d spent the past couple of days with his fiancee and the mother of his kids, Chloe Mendel. At recent concerts, he has also taken to inviting his boy and girl up on stage to dance beside him, wearing earmuffs, while the crowd cheers them on.

This evolution of the head Pumpkin into dad mode has been heartwarming for longtime fans, not least because he appears to be actively breaking the cycle of abuse and neglect that his own parents inflicted on him. The hard truth, though, is those harsh early experiences galvanised his desire to succeed. His rage was a fuel that burned bright for a while, but was ultimately unsustainable.

“I knew at a fairly young age, in my late 20s, that my success in music was not going to get me the happiness that I thought it would – but I didn’t know what to do about it,” he says. “Having children at a late age has really helped me find some perspective that I couldn’t have found on my own.

“I certainly know that having children made me think, ‘I care about how they would see me’,” he says. “I didn’t want my children to see me as somebody living in the shadow of another time: I wanted to be present in this time, so they would look at me and be proud of me.”

On the screen during our video call is a 55-year-old dad in a comfortable beanie and scarf, lying on his bed at home, laughing at the sheer absurdity of his younger self and the hubris that drove him back then. The old dreams are long dead, but the new ones twinkle before him like so many jewels.

The Smashing Pumpkins’ tour with Jane’s Addiction begins in Brisbane (April 15) and ends at the Gold Coast (April 30). ATUM: Act Three will be released on May 5 via Martha’s Music.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout