Australian galleries neglect Dante milestone

This year marks the 700th anniversary of the death of Dante Alighieri. Yet not one of our national or state institutions seems to be marking the anniversary in a significant way.

This year marks the 700th anniversary of the death of Dante Alighieri, the greatest author in Italian and among the supreme writers in the canon of world literature. His masterpiece, La Divina Commedia, set at Easter 1300, was completed in 1320. Accordingly, this is a year of important commemorations and celebrations in Italy, and yet in Australia – even with so many citizens of Italian descent – not one of our national or state institutions seems to be marking the anniversary in a significant way.

Unfortunately, this omission is not entirely surprising considering the apparent mindset of the directors and boards of most of our big galleries. Money, politics, fashion and marketing seem to loom far larger in their mental worlds than art, literature or ideas. I wonder how many of them have even read Dante; and clearly they have not given much thought to his remarkable impact on modern culture.

The history of Dante’s reception is uniquely interesting. In Italy he always remained the supreme poet and the most important contributor to the development of the Italian language: he used, for example, around 28,000 words at a time when his friend and mentor Guido Cavalcanti made do with some 800. In Michelangelo’s Last Judgement (1537-41), the group of Charon and his boat, on the lower right, is drawn directly from Inferno III, 105 ff. This reference completely escaped a French commentator in the 17th century, who angrily complained about pagan figures intruding into a sacred scene. In fact, it is through such syntheses that Dante is both the greatest of medieval poets and one who transcends the Middle Ages in his attunement to antiquity and his anticipation of the renaissance.

Outside Italy, few were aware of him. In England, the brilliant and eccentric Sir Thomas Browne (1605-82) was clearly a reader; Milton too was well aware of his great predecessor. Otherwise Dante’s vision of the afterlife was too Catholic for Protestant tastes, and too otherworldly for the Scientific Revolution and the 18th century Enlightenment. For almost 500 years, his work was not even translated into English. But all that changed with the Romantic movement, which discovered that the world, and human beings, were not clockwork after all.

Dante was the most important literary beneficiary of this movement. In 1782, Charles Rogers produced an English version of the Inferno, and in 1802 the first full translation of Inferno, Purgatorio and Paradiso was published by Henry Boyd. English readers fell in love with Dante, and in the two centuries since that time, more than 100 translations have appeared: the Wikipedia page “English translations of Dante’s Divine Comedy”, based on but extending to Gilbert Cunningham’s 1966 critical bibliography, gives some idea of a phenomenon that can only be compared to the English translation of Homer. Recent versions that have been widely read include Dorothy Sayers’ Penguin edition (1949-62) and the newer translation by Mark Musa, also published in Penguin Classics, in the late 1990s.

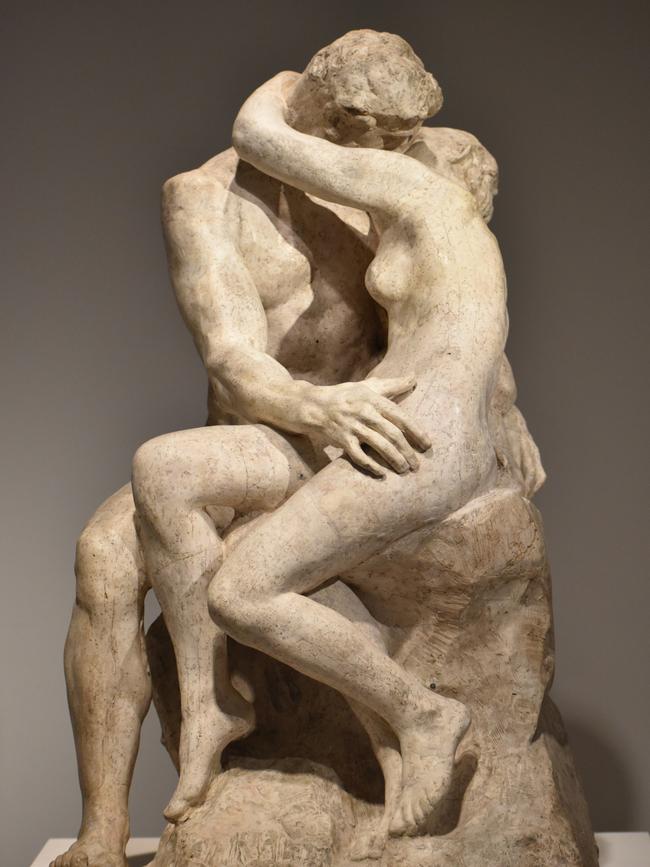

At the same time, after having been ignored through the early modern period, Dante suddenly became a central reference for modern art and literature. William Blake produced a series of watercolours, many of which are in the National Gallery of Victoria collection. Countless other painters depicted famous episodes, especially from the Inferno; he was the most important inspiration for Auguste Rodin, not only for the Gates of Hell project but for individual works such as The Kiss, The Thinker, Ugolino and His Sons. He was equally influential in literature, especially on modernist authors such as James Joyce, Ezra Pound and T.S. Eliot; The Waste Land (1922) and The Hollow Men (1925) are incomprehensible without reference to the Divine Comedy. Eliot’s important essay on the poet (1929) inspired many English readers to start reading Dante, and even to learn Italian.

As we make our way through winter, some of us in lockdown, there is an excellent opportunity for readers to discover this great author for themselves, and indeed to venture into the Italian language as well, for many English editions of Dante – unlike those of most other authors – include the original text in parallel to the translation. If you don’t have a copy at home, Dante is of course available online, including Mark Musa’s version and various parallel texts. And I highly recommend searching “Roberto Benigni Canto 1 Inferno” on YouTube for a wonderful performance in the original Italian (with English subtitles available).

As it is now impossible for me to travel interstate and as all galleries even in Sydney are closed, I am going to devote the next few columns to a series on romantic and erotic themes in art and, as it happens, Dante makes a good starting-point, not only because his work includes some of the most famous love stories of all time, such as that of Paolo and Francesca which is told in Canto 5 of the Inferno and was the inspiration for Rodin’s The Kiss, as well as many other works, but even more importantly because Dante’s whole conception of the cosmos is grounded in the idea of love.

The very occasion of the poem is the ideal love for a young girl called Beatrice that Dante had evoked in his earlier work, La Vita Nuova, published in 1294, four years after her death. At the beginning of Inferno, Dante imagines himself having reached the canonical midpoint of life (Psalms, 90:10), the age of 35 – nel mezzo del cammin di nostra vita – and finding himself morally and spiritually lost. Beatrice intercedes with the Virgin Mary on his behalf and he is allowed to visit the world of the afterlife: Hell and Purgatory with Virgil as his guide, Heaven with Beatrice herself.

Dante’s vision of this world is completely different from the scenes of hell painted on the walls of contemporary churches, in which the lustful are hung up by their genitals on butchers’ hooks, sodomites are roasted on spits and the avaricious have molten gold poured down their throats.

It is far more intellectually sophisticated and morally coherent, as well as complex in the way that it can, for example, evoke our sympathy for individuals whom we nonetheless recognise as inevitably condemned for their actions.

Dante’s world rests on the infrastructure of the scholastic philosophy of Saint Thomas Aquinas, who in turn relied on Aristotle as his foundation. When Aristotle asked how God or the prime mover actually moves the cosmos, he replied with stunning concision: “he moves it as being loved” (Metaphysics, 1072 beta); in other words God does not cause things to happen by prodding or pushing, but by being the object, centre and end of all desire. Everything in the universe is drawn to the divine essence and seeks its proper place in the cosmos structured by divine love.

Thus sin is essentially a perverse refusal to align ourselves with the order of the world. If we take the traditional seven deadly sins, lust, gluttony, avarice, sloth, anger, envy and pride, we can see that the first three are comparatively less serious because they represent excessive love of things which it is proper to love in a moderate way. Indeed sloth or accidie, which is a sullen refusal to enjoy the world, is a more grievous sin than the overindulgence of lust or gluttony. The last three are worse again because they represent the perversion of love into hate.

Dante’s hell includes a special section which is free from suffering and is reserved for the virtuous pagans and the patriarchs of the Old Testament; this is where Virgil usually spends his time with the other great poets and sages of antiquity. Particularly interesting is the swarm of dead souls blowing around in the wind that they encounter just inside the gates of hell: these are the souls of those who were neither good nor bad, who took no responsibility in their lives, and who are now refused passage across into the underworld. Their number is so great that Dante is astonished: as Eliot translates the line in The Waste Land: “so many, I had not thought death had undone so many”. And these are also the prototypes of Eliot’s “hollow men” a few years later.

As to where we belong in the afterlife, Dante does not need devils with pitchforks to drag us to our punishments: for when we die, we lose our capacity for self-deception and we understand perfectly clearly how good or bad we are.

At the same time we lose the free will that we enjoyed in life and we find ourselves, as it were, connected directly to the universal will of God: so as well as knowing exactly what our place is in the afterlife, we cannot but will to be in that place. It is no longer possible to want anything other than what is.

The second section of the great work is Purgatory, a place where those whose sins were not irredeemable can be cleansed of their traces and prepared for eventual admission into Heaven. Dante imagines this as an island in the South Seas, at the antipodes of Jerusalem. It is guarded by Cato the Elder and is conical in shape, with a path winding up it in a spiral. At each level, souls are purged of their sins, starting with the least serious, and at the top they reach the level of the earthly paradise or Garden of Eden.

In Heaven itself there are many levels of blessedness, ultimately depending on the spiritual development attained in this life, but once again each soul is naturally in the place in which it belongs and cannot conceive or wish for the higher levels of happiness that others may experience. This book was no doubt the hardest to write, for it is obviously more difficult to evoke successive degrees of blessedness than to dwell on the sufferings and pathos of the wicked. And for this reason the majority of those who have attempted to read Dante have probably only finished the Inferno, or even part of that book.

In reality, Paradiso contains some of the very greatest passages of literature ever composed, especially in the final canti, where Dante approaches the highest levels of Heaven. Here he glimpses the world as it appears from God’s point of view, the opposite of our anthropocentric one. There is an extraordinary passage in which he speaks of seeing things that exceed the power of understanding of the human mind and of which therefore he cannot give a clear account. But in one beautiful metaphor – the great medieval image of the book – he imagines the disparate multiplicity of the world, like scattered pages in our ordinary experience, legato con amore in un volume – bound together by love into a single volume.

Eros in art

Part 1: Dante and the Divine Comedy

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout