Artists bore witness to the events that led to the raising of the Eureka flag

Most misleading is the casting of the Eureka riot as some kind of ‘democratic’ uprising against the British government, as though Australian democracy had arisen out of a revolt against British rule. Australia’s democracy was actually inherited from Britain.

Upheaval on the Goldfields is a small exhibition at the Art Gallery of Ballarat, largely composed of amateur and documentary works and of minor aesthetic interest in its own right, yet worthy of attention for the light it may shed on a very unusual, highly-charged but deeply ambivalent and ultimately questionable piece of Australian iconography, namely the so-called Eureka flag.

Casual visitors to our country could justifiably be confused about the meaning of this banner. They might see it worn by bikies, or associated with certain kinds of unions, such as builders or dockers, or again waved in far-right or white supremacist demonstrations. The only obvious things these groups have in common are a sympathy for anarchism. It would come as a considerable surprise to discover that some people associate the flag, as the wall text at the opening of this exhibition recalls, with “the birth of Australian democracy”.

But even without the elements of violence, it is hard to see how an armed uprising of miners protesting against government taxation could be considered either heroic or democratic, from almost any political perspective, but especially from a left-leaning one. In Australia today, the question of whether our mining companies – admittedly large corporations, not individuals – pay an appropriate level of tax has been a subject of lively debate. And Kevin Rudd’s fall as Prime Minister, to be replaced in a party-room coup by Julia Gillard in June 2010, was brought about in large part by his attempt to introduce a mining super-profits tax.

Nor is mining very popular today with the ecologically minded, although at least big corporations are now obliged to set aside huge sums of money for environmental remediation after the closure of the mine (and this is why we have recently seen still viable operations sold for almost nothing because the remaining production of the site is unlikely to exceed the remediation costs by any appreciable amount).

In the gold rush, as countless contemporary images prove, poorly regulated miners reduced whole landscapes to toxic wastelands. Areas in the Amazon that have been stripped and turned into mud pits for goldmining today – as documented in the Richard Mosse film I reviewed here some months ago – give us an idea of what the mining areas looked like.

Undoubtedly the miners had some legitimate grievances with a system that could be unfair or inconsistent, and which could be policed in an arbitrary and even predatory manner. But neither the cause nor the moral character of the gold miners was particularly admirable; these were not the Pilgrim Fathers of New England, sailing across the seas to find freedom of worship; they were adventurers and sometimes ruffians from the four corners of the world, driven by the ancient and, as Virgil said, accursed lust for gold. No doubt some also had much finer qualities that would come out under different circumstances; but others must have been a rabble eager for personal enrichment.

So it is not surprising that these would-be democrats, although no doubt compelled by their very diversity to embrace a certain cosmopolitan tolerance, could also be racists and bigots. Just a couple of years after the “upheaval” in Ballarat that culminated in the battle of the Eureka Stockade on December 3, 1854, mobs of miners attacked the growing Chinese population in what are known as the Buckland riots of 1857.

These were the kind of people who helped develop the White Australia policy, later promoted by the Labor Party and intended to protect the working-class from what was considered unfair competition from Asians willing to work harder and accept lower pay. It is an irony that the abolition of this racist policy by the Holt Liberal government in 1966, whose measures were extended by the Whitlam Labor and Fraser Liberal governments, was soon afterwards followed by the wholesale export of working-class jobs to China in the process of globalisation.

Most misleading of all, however, is the casting of the Eureka riot as some kind of “democratic” uprising against the British government, as though Australian democracy had arisen out of a revolt against British rule. The democracy we enjoy in Australia today was not won in resistance to Britain, but directly inherited from Britain. The only real question, and a far less significant one, was the timing of the transition from direct colonial administration to responsible government at the level of each colony and eventually to full autonomy.

Australia was in reality extremely fortunate to be settled by Britain, especially when we consider any of the alternatives. It is not simply that – for all the legitimate and serious criticisms that can be made of the settlement process – Britain was a better colonial administrator than any other European power; in the long run it is above all that the Westminster system of liberal democracy works better than the alternative models. Though far from perfect, it is flexible, generally effective and open to a continuous process of adjustment and improvement.

READ MORE: The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood captured politics, sex and religion * Why the art world is obsessed with Saint Francis of Assisi * Why some of Australia’s best art can be found in the regions

Notably, the ingenious combination of constitutional monarchy – a symbolic executive with authority but not power – with a ministerial government arising organically out of the legislature, is preferable to the presidential system whose deficiencies we can see in such republics as France but most conspicuously, even disastrously, in the United States. It is characteristic of British institutions that this system diverges from the strict doctrine of the separation of powers but works better than those which observe the principle to the letter.

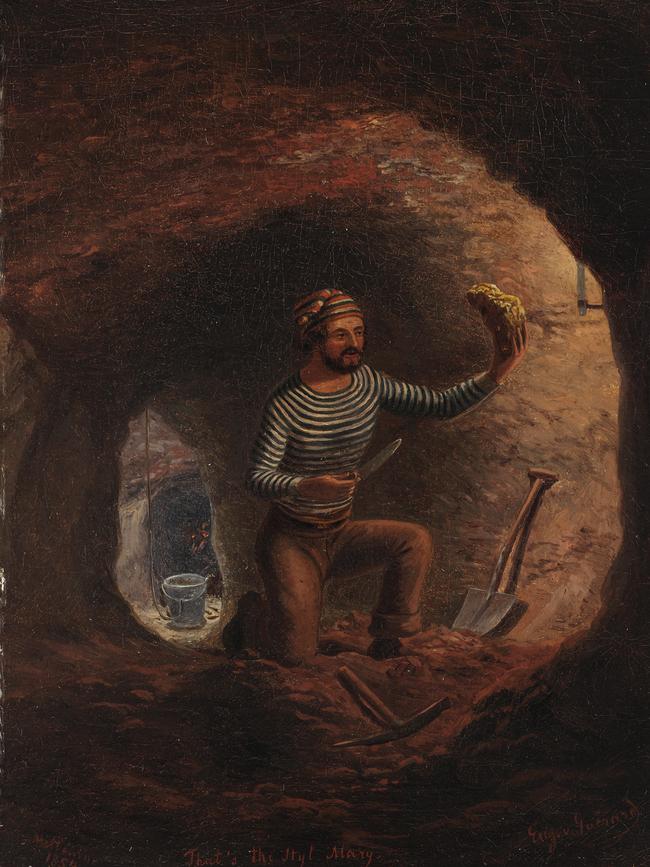

The most aesthetically significant works in this exhibition are two paintings by Eugene von Guérard, who although already a highly-skilled painter had himself come out to try his luck on the goldfields. A small sketch shows a miner in an underground tunnel who has discovered an immense nugget, like an image of every miner’s dream.

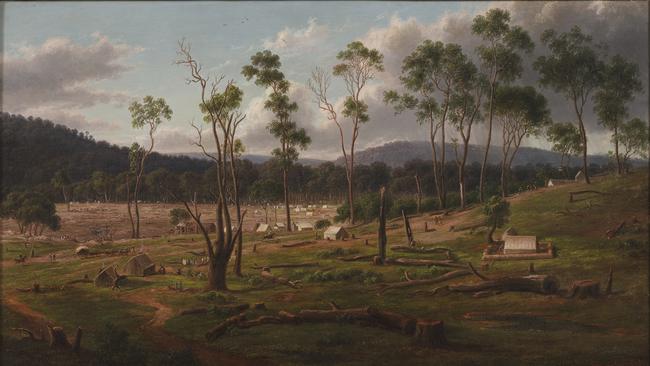

A larger painting, Golden Point Ballarat and flat, with part of Black Hill, as in July 1853 (1874), is clearly a retrospective view completed from contemporary sketches, and represents a site he knew well and first saw in January 1853. In his diary for January 18, the artist writes: “After travelling for a week we have arrived at Ballarat … Ballarat consists of a camp of tents, and some buildings constructed of boards. One building, made of the trunks of trees, constitutes the prison, and is often the temporary abode of bushrangers, and also of diggers who can’t – or won’t – pay their licence.”

This makeshift lockup, with its tantalising anticipation of the events of the following year, may be one of the timber structures on the left of the composition. On the right is what appears to be a tent erected inside an enclosure bounded by a low stone wall. Could this be the hospital?

The rest of the view is dotted with tents, often with the surprising addition of a chimney: Von Guérard writes of building one for his own tent on May 7; the impact of mining, even in these early days, is indicated by the cut tree stumps, fallen logs and dead trees still standing that form a sharp contrast with the graceful natural forms of the surviving trees in the middle distance. He describes the effort of felling trees himself on September 18, 1853.

Three stumps conspicuously mark the foreground of Von Guérard’s composition, and the space is measured in depth by a series of fallen trunks roughly parallel to the picture plane; on the far right, a tree has been cut down but its trunk is still connected, awkwardly and at right angles, to its stump. All of these elements – as in some other pictures by the artist – acknowledge the destructive effect of land clearing on the environment, and yet the overall effect of the composition is serene, as though the frenetic activity of man were trivial and superficial compared to the enduring life of nature evoked by the mountainous background and the sky above.

The events of the following year are illustrated in two watercolours by the Swiss-Canadian artist Charles A. Doudiet (1832-1913). These are part of a previously unknown sketchbook rediscovered in 1996 and acquired by the Art Gallery of Ballarat. They are obviously of great interest as eyewitness records of the events and incidentally as evidence that the Eureka flag held by the Ballarat gallery is the original one raised by the rebels.

A doubt was raised about the authenticity of the sketchbook, and discussed in an article in The Age (“Flagging the truth”, January 8, 2012); it would, however, be necessary to see the whole sketchbook and examine it in detail to have any valid opinion on the matter. There does not appear to be anything in the watercolours themselves to warrant suspicion, although an expert on the period would want to consider whether details such as the buildings in the background correspond to what we know from other sources. In any case, one of the watercolours is inscribed with the date 1 December 1854, and the title Swearing Allegiance to the Southern Cross. In the centre is a miner holding a rifle and standing on a tree stump above which the Southern Cross flies from a flagpole. Around him kneel half-a-dozen other armed miners raising their right hands in an oath – a distant echo of great oath-pictures of the neoclassical period, such as Hamilton’s Oath of Brutus (1763-64), Fuseli’s Oath on the Ruttli (1779-80) and David’s two famous compositions, the Oath of the Horatii (1784) and the Tennis-court oath (1790-94, never completed).

There is a wide empty space around the central group, and then all the other miners in a ring around the periphery. A couple of men on horseback are seen on the right and left of the composition, the latter seemingly having an altercation with some of the miners; perhaps these are some of the mounted inspectors who would look for derelict miners. This scene was a couple of days before soldiers and police stormed the barricade at dawn on December 3.

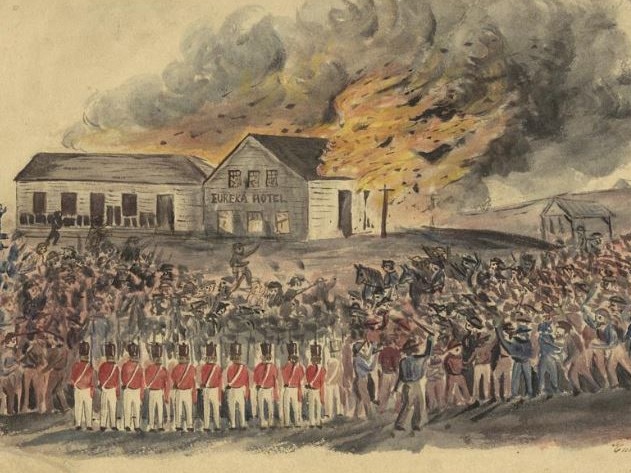

The other scene exhibited records an earlier episode, predating the raising of the Eureka flag, and showing the burning of the Eureka Hotel by rioting miners on October 17, 1754. A double line of soldiers, perhaps 20 in all, stands in the foreground, uncomfortably close to the mob. One might attribute this to an amateur’s lack of skill in rendering space, except that the miners on the right are next to the soldiers, and indeed this is consistent with the Melbourne Herald’s report (October 20) that they were too few in number to prevent the attack. And limited though Doudiet’s ability as a painter may be, he appears to have had a sense of his responsibility as a witness to events of some importance and of the duty to record them for himself at least, if not for posterity.

Upheaval on the Goldfields, Art Gallery of Ballarat, until August 13.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout