Art of suburbia: Why identical houses on small blocks are bad for the soul

Houses in the most pleasant suburbs of Sydney are on generous grounds where owners spend time in the garden. But venture to the new fringe suburbs and you hit a cultural wasteland.

It is no coincidence that the words city, citizen and civilisation are all cognates. It was only after the Neolithic Revolution, starting about 10,000 years ago, that humans developed agriculture and began to move from hunter-gatherer cultures, living more or less nomadically in small tribal groups, to urban settlements in which agriculture could feed a far larger population and the division of labour allowed members of the community to specialise in particular activities. Cities thus became the centres of far more complex societies and cultures than could develop in prehistoric times.

But the city as a political entity really came into its own in ancient Greece – the word ‘‘politics’’ itself comes from ‘‘polis’’, the Greek word for a city – and much of the originality of Greek civilisation can be ascribed to the social conditions that arose during the Archaic period in the seventh and sixth centuries BC. The most decisive of these was that ancient Greece was never a nation, but a constellation of autonomous city-states that proliferated across the Mediterranean, from the coast of Anatolia to Sicily, Southern Italy and the south of France, by a process of colonisation akin to cell-division. And each of these city-states was, almost from its very foundation, autonomous and self-reliant.

This produced socio-political conditions favourable to a culture of great energy and diversity. Rivalry between individual city-states often resulted in war, but also found peaceful expression in the great Panhellenic festivals like the Olympic, Isthmian and Nemean Games; these occasions were considered so important that mandatory truces allowed both athletes and spectators to travel safely even through enemy territory to attend them. The rival cities were also united by a common language, religion and veneration for the Homeric epics, the Iliad and the Odyssey, as the fountainheads of literature.

Rivalry and the spirit of competition were powerful within the city-state as well. Factionalism was often intense, and led to alternations between different forms of government: monarchy, oligarchy, tyranny and later increasingly democracy. But whatever form of government prevailed, it had to guarantee the security of the state, since each city was ultimately obliged to stand up for itself and defend its citizens from external threats. Even before the emergence of the Athenian democracy, the conditions of existence of these city-states meant that every citizen was a responsible member of the community who would have to fight in the event of war and therefore inevitably had a stake in the life of the city. A monarchy or tyranny or other form of government might be supported or tolerated as long as it provided effective leadership, but if it failed it would swiftly be overthrown and replaced.

The polis was thus the crucible of Greek political, social and cultural life. It is from this word and concept that we derive not only ‘‘politics’’ and ‘‘politician’’, as already noted, but also the words ‘‘policy’’, ‘‘police’’ and even ‘‘polite’’, since people living in the city had to learn to deal harmoniously with sometimes quarrelsome fellow citizens. In the same way, the word ‘‘urbane’’ derives from the Latin word for a city. And it was this same crucible that established what are still the axioms of democratic political life today: the rule of the law, the responsibility of the citizen and government based on the will of the majority.

The Greek model of political life evolved during the Archaic period, in the 7th and 6th centuries BC, and was tested in the Persian Wars of 490 and 480 BC when this decentralised collection of independent states succeeded in defeating the greatest empire in the world. Buoyed by this extraordinary triumph, Greece experienced the flowering of the Classical period over the next two centuries, ending with Alexander’s conquest of the Persian Empire. A unique mix of individual ambition and initiative with a fundamental sense of political community and responsibility – animated by the powerful and quintessentially Greek ideas of freedom and independence – ultimately prevailed over a vast empire that understood none of these ideas.

Two thousand years later, some of these conditions were repeated in the emergence of the Italian city-states of the renaissance period. It is often and rightly pointed out that the civilisation of the renaissance in Italy – to cite the title of Burckhardt’s great book on the subject (1860) – has important roots in the preceding medieval period, but the crucial factor is the rise of independent city-states, again jealously independent and ambitious in their mutual rivalry. The process reached its most sophisticated development in Florence, where Vasari rightly ascribed the flowering of renaissance art to the spirit of emulation that made each man want to excel in whatever he did. No story illustrates this better than Brunelleschi’s refusal to collaborate with Ghiberti on the Baptistery doors and his decision to make his mark with something no one else had succeeded in doing, by designing the cupola of the Cathedral of Florence.

But if the city is the epicentre of civilised life, what are we to make of suburbia? As the word, with its Latin origins, suggests, the word denotes areas around and outside the city proper. It is not the centre of social life, but originally a place of respite on the periphery of the busy centre, where people can enjoy relative peace and calm and the pleasures of a semi-rural environment, with gardens, orchards, flowers and even domestic animals. And that is what the suburbs of modern cities were originally like too – indeed even today houses in the most pleasant suburbs of a city like Sydney can be set in generous grounds and their owners take pleasure in relaxing among the trees or working in their gardens, growing their own fruit, vegetables and flowers.

Increasingly however, especially in the middle of last century, populations moved out of the centres of our cities, resulting in a kind of hollowing-out of urban culture and a displacement of the residential centre of gravity to suburbs which represented an altogether different kind of life. Instead of being leafy and semi-rural areas on the fringes of the city and within relatively easy reach of the centre, suburbs grew into vast cultural wastelands of almost identical houses on small blocks with a backyard rather than a garden; and then the houses started to expand and take over more and more of their blocks. There has of course been significant regeneration of inner-city quarters in the last 50 years, but it has had little impact on the still increasing suburban sprawl, an environment designed for consumers rather than active participants in culture.

At the same time, most of these houses were designed for the so-called nuclear family, an inherently unnatural social unit. In the extended and multi-generational family, there is a natural transition between the roles of children, parents and grandparents, who help to look after small children and reduce the considerable stresses on a young couple, especially when both parents are working. Such an arrangement largely obviates the need to pay for children to be minded by strangers; everyone is more sociable and less exposed to loneliness in a larger family group, and culture is passed on at the family level from older to younger generations.

The suburban world represented in this exhibition reflects the banal reality and even grimmer perception of the world in which most people today grow up. It is striking, even on a casual walk through the show, that none of these pictures evokes the pleasures of suburban life at its best; no one is gardening or tending an orchard or flowers. In fact, with the exception of one series in which feckless and alienated youths drift aimlessly around a front yard, there are no human figures in the exhibition at all.

What kind of a social environment is it that is so starkly uninhabited? There are blocks of flats, the best images of which belong to the familiar pictorial world of Peter O’Doherty, but mostly small self-contained bungalows. They are solidly built, not hovels, and yet architecturally completely uninteresting. The absence of human figures leaves us to imagine a suffocating world inside: the living spaces dominated by a giant television, the parents’ quarters in which the couple try to preserve their original closeness and intimacy, the children’s rooms in which growing boys and girls struggle with their anxieties and neuroses and sink into treacherous worlds behind the ever-present digital screen.

Some of the pictures in this exhibition are more memorable than others. Robyn Sweaney’s little portraits of suburban cottages are striking for their precision of detail and understated plainness. Christopher McVinish, on the other hand, makes expressive use of late afternoon light and gathering storm clouds in a series of pictures sharing a title that leaves little doubt about his view of his subject: The Faded Dream. In one of these, the windows of the house are a sinister and funereal black while the light catching the postbox on the lawn makes us wonder whether the house does in fact receive any mail at all.

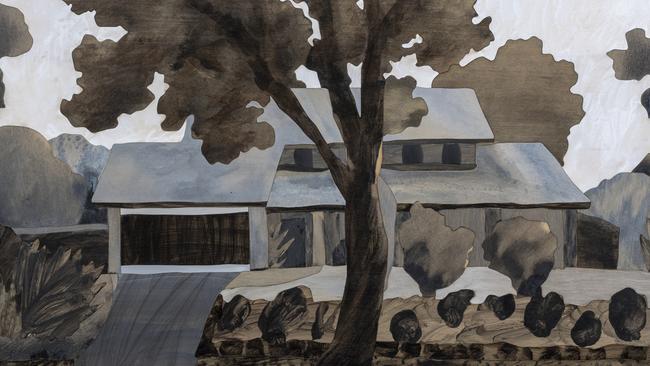

Alan Jones’s Painting 244 (Tamarisk Crescent), with its limited palette and above all its framing of the suburban house in a natural setting including a large tree in the foreground, hints at a more harmonious and less alienated vision.

Catherine O’Donnell’s fine pencil drawings are acutely observed and agnostic in their lack of implicit judgment on dwellings and details – like a window with Venetian blinds – that she finds formally interesting. Only in a long drawing of an apartment block is there a sense of claustrophobia and confinement.

Two large paintings by Noel McKenna are marked by his characteristic sense of whimsy; one has three Queenslanders, houses raised on stilts, in a green field, and the other has a single house, this time on implausibly tall stilts, near a body of water on which a man rows away in a dinghy; the work is titled Remember to come home. Rachel Ellis’s two paintings offer a more open view of suburbia with space, light and trees, even if in one of these pictures the crowns of the trees have been mutilated to accommodate power lines.

On the whole the paintings are more interesting than the photographs in this exhibition, but some of the paintings are fairly insubstantial as well, either offering facile images of faceless blocks of flats or turning their subject-matter into rather vacuous decoration.

I can’t help feeling that a number of the individuals represented here could have been replaced by better painters, such as – much as I hesitate to mention artists known to me personally – Kevin McKay in Sydney and Joe Whyte in Melbourne.

Paintings by these two, and no doubt others, could have lifted the overall quality and interest of the exhibition and added more nuance to what is otherwise a perhaps exaggeratedly bleak view of life in Australian suburbia.

In Suburbia. S.H. Ervin Gallery, until May 4

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout