Noel McKenna, Landscape — Mapped: pictures into our true hearts

Noel McKenna’s maps show Australia from unexpected angles that lend a kind of surprising enchantment.

The earliest literary description of a map seems to be in Aristophanes’s Clouds, a comedy about the vagaries of contemporary philosophy first produced in Athens in 423BC. Because of the play’s subject, it includes many references to arcane intellectual speculations and to scientific instruments and devices, including the lens and the way it can be used to light a fire.

But in the scene with the map, the ignorant protagonist is shocked to see how close Athens is to its traditional enemy, Sparta, and naively asks whether it cannot be drawn farther away. Maps must have been something of a novelty at the time for such a mistake to be plausible, but familiar enough for the audience to have found the question hilarious.

Maps have this kind of stubborn factuality, yet they also can be imbued with an irresistible power of enchantment. Who has not pored over one, planning an itinerary, and wondered at the imaginative power of names, filled with associations of history and literature, personal memories and tales we have heard? Readers of Proust will know that this is a favourite theme of his; but so is the elusiveness of this mysterious essence once we reach the place itself.

This is partly because the name contains so many ideas and echoes that we may not immediately discover in the busy streets of a modern city — especially as everywhere, today, is becoming more like everywhere else — but also and equally importantly because wherever we go, we bring ourselves and our self-centredness. How often have you seen people in the most beautiful and historic places in the world talking obsessively, and usually complaining, about their family, friends or neighbours at home, chewing over their dissatisfaction and unhappiness like a cow chewing cud in a field?

These questions are particularly interesting to anyone who aspires to be a traveller in an age of increasingly obtuse mass tourism, and I reflect on them also as someone who takes a sort of busman’s holiday every year leading groups of art lovers around the Mediterranean and more recently Iran. There is no simple formula, but real travel begins at the intersection of the past and the present, as in Peter Robb’s Midnight in Sicily (1996) or Street Fight in Naples (2010), where antiquity, the Middle Ages and the baroque weave in and out of the life and dramas of these cities in our own day.

Presumably foreigners gaze at maps of Australia with some mysterious sense of strangeness and the promise of adventure but, to most of us, the map of our continent, though impressive in scale, offers little in the way of enchantment. Our toponyms are an alternation of borrowed British and Aboriginal ones, of which only a few manage to have any kind of resonance, suggesting ways of life that are eccentric, gracious or alternative, or recalling towns and cities with some architectural character. Obviously it would be invidious to cite examples.

But this is what makes Noel McKenna’s map project so interesting. The artist, who has always been known for a mixture of whimsy and a kind of faux-naif surrealism, has produced during the course of 1½ decades a series of maps of Australia that show the country from quite unexpected angles, but ones that do in fact lend it a kind of surprising enchantment.

McKenna has focused not on objective facts of geographical co-ordinates, natural features and topography but on motifs that speak implicitly of the social and cultural life of Australians, and of our experience living in this land. A dramatic example is the map of all the lighthouses in Australia, where the map is painted black and the lighthouses are bright points dotting the coastline. There are more of them than we may have guessed, and the image poignantly evokes a vast and almost empty continent with an immensely long coastline.

Less dramatically, there is for example a map of all the municipal swimming baths in Australia, which is almost a proxy for a map of the settled and inhabitable parts of the country, since any town of any size will have a swimming pool. As the many pools in the larger cities cannot be shown on the map, they are listed in adjacent boxes. McKenna’s survey does not include ocean pools or the private facilities of schools and universities — nor, of course, pools on private properties.

A parallel phenomenon is registered in another map, of all the racecourses in Australia. Here there are only a few in the main cities, even if they are the principal national ones, but countless smaller tracks in country towns, some of them used only a few times each year for local racing events. This map, too, says something about population distribution — though perhaps more about population before the great move to urbanisation during the past century — as well as much about the culture of the horse and of gambling in Australia.

Related to the question of population, and perhaps closest to a conventional map of a specialised kind, is McKenna’s survey of the railways of Australia.

This map reminds us that the national network is in reality a group of state networks, but also of the even more incomprehensible fact each state system, originally established during the colonial period and well before Federation more than a century ago, was built with different gauges. In hindsight it is almost impossible to imagine how colonial administrators could possibly have thought it rational to adopt different gauges when building from scratch in a single continent.

The network has been extended in some areas during the past 100 years, but it also has shrunk in others, and many regional lines have been allowed to fall into disrepair. The direct line from Geelong to Ballarat, for example, was opened in 1862 and ceased operating passenger services in 1978. This sort of shrinkage has accompanied the atrophy of regional cities and the spread of private car ownership, which together have exacerbated the bloated urban sprawl of our main capital cities.

McKenna’s map, revealing the paradoxically more ambitious transport infrastructure of the century before last, reminds us how improved train travel and the introduction of fast trains could make life in the country a viable, and indeed far preferable, alternative to a wretched existence on the fringes of Sydney or Melbourne. In Europe, the Eurostar train service has just been extended to provide travel from London to Amsterdam, and the new and more leisurely service is expected to take a huge section of the market now serviced by air.

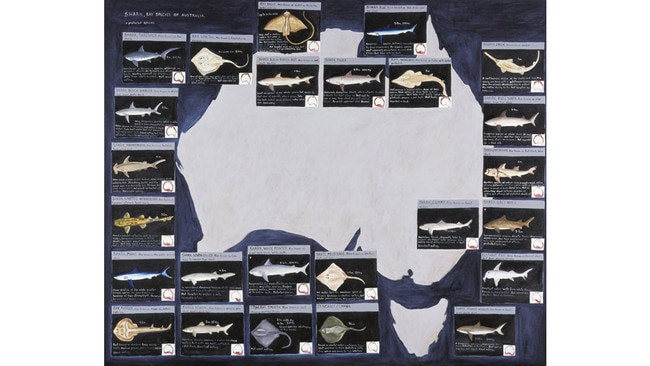

Human presence and the things that we have built are not the only things that interest McKenna. There is a map of butterflies of Australia; another of river fish, reflecting the interests of a keen fisherman who seems to write from experience; and another of the sharks of Australia that also incidentally notes which ones are good to eat. But especially notable is the map of all the dangerous things in Australia, in which McKenna has catalogued not only all our deadly spiders and venomous snakes — including a newly discovered but fortunately rare one that is even more deadly than those we already knew — but even insects, jellyfish and poisonous plants of several varieties.

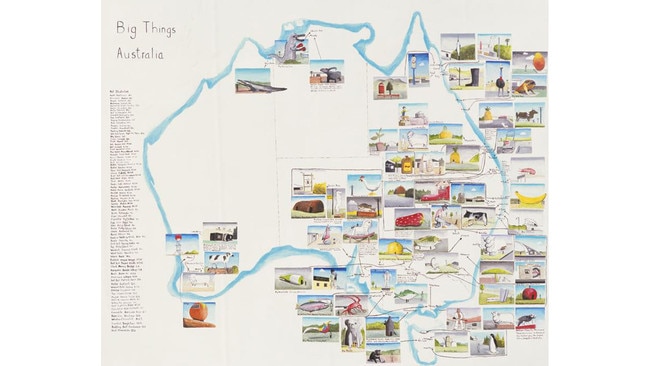

One of the most characteristically whimsical maps is of Big Things in Australia — the famous Big Pineapple, Big Banana, Big Penguin and other quaintly kitsch pseudo-monuments that are attractions in so many country towns. And here we can see how McKenna’s own clearly spontaneous fascination for such subjects, which is akin to that of any obsessive collector of ephemera, also takes on the character of a sort of conceptual art. It unexpectedly shows how this kind of art — which had its heyday a half-century ago — inherently predates the internet, which makes everything at once too easy and too impersonal.

Instead, McKenna’s Big Things project relied on writing to municipal authorities all over Australia, and asking for information about, and preferably images of, any Big Things they had in their town. Often he included a stamped, self-addressed postcard to make it easier for them to reply. All of these materials, as in the conceptual work of artists such as Robert Rooney, become part of the project and are duly collected in archive boxes. Meanwhile, his map of Australia was annotated and illustrated with little paintings of the various Big Things.

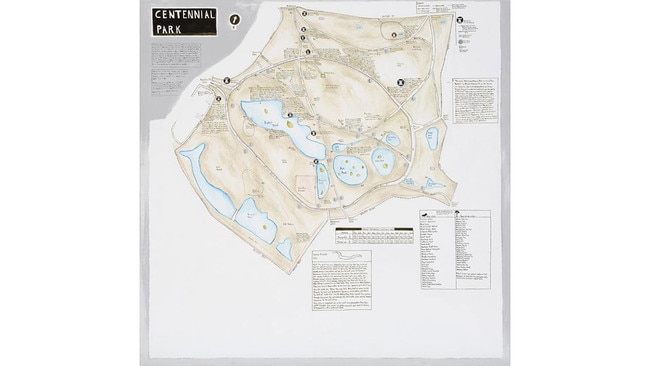

This conceptual character of McKenna’s work is even more evident in the last wall of works, the first of which is a documentary map of Centennial Park, with details of the various ponds, roads and built structures, and a fascinating note about the eels that live in the park’s ponds but every year slither out of the water and make their way, via an interconnected series of wetlands, to Botany Bay, from where they swim to New Caledonia to spawn and die; the tiny elvers then instinctively swim all the way back to Botany Bay and return to the ponds they presumably have occupied for thousands of years.

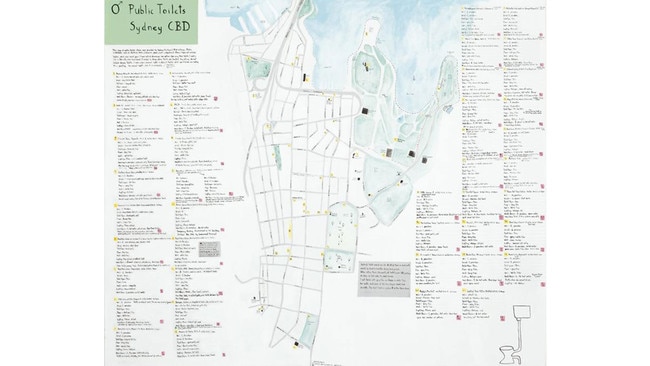

Equally interesting, far more eccentric yet also very much in the conceptual tradition is a map of the public toilets of the Sydney CBD. Once again there is a methodical, low-tech and first-hand documentary approach that even has overtones of performance art. McKenna has visited and used each of the public facilities in his survey, and has assessed each on a set of common criteria, from the state of lighting and decoration to the quality of the toilet paper, noting in passing any unusual activities that he witnessed in the course of his research.

The last two works are autobiographical. There is a map of Brisbane, where the artist spent his early years, and where he has marked the sites of all the important events of his childhood, adolescence and art-school years. It is a sample of the millions of different networks of memory, invisible pathways of habit and markers of significant events, that overlay a city in the minds of each of its inhabitants.

The last piece is not really a map but a graph, and it records not space but time: in pondering how to chart the progression of his life so far, McKenna decided that his level of happiness was the most important factor, and so the graph follows his state of mind in childhood and into adolescence and adult life.

There are some changes that are expected, such as sadness at the death of his first dog, but others that are less predictable, such as a decline after the birth of his first son.

Other changes too, though not necessarily dramatic, raise more questions than they answer. The life of an individual, clearly, is as hard to chart in a single and straightforward way as that of a nation.

Noel McKenna: Landscape — Mapped

Queensland Art Gallery, Brisbane, until April 2.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout