All the silk roads lead to this outstanding British Museum show

The British Museum is staging a staggeringly ambitious exhibition of the ancient trading route connecting East and West.

The names of foreign places can be filled with an inexplicable magic, as all travellers know, even in an age when this magic is ruthlessly exploited by the tourism industry. It is a theme eloquently written about by Marcel Proust, but one that first really appears in Latin poetry, filled with evocative names of places in the Greek world or even beyond, in the fabled orient. And yet Latin authors are also the first to point out – as Proust would also later – that we do not actually become a different person in a different land. Horace famously wrote that those who go abroad change the sky, not their minds (Epistles I, 11), and later Seneca, in Letter 28 and citing Socrates, asks his younger correspondent Lucilius why he imagined he would escape his cares and anxieties on an overseas voyage. Our faults follow us wherever we go; but if we can find peace of mind, we can be happy anywhere.

Perhaps no toponym carries a deeper charge of exoticism than the Silk Road, in reality a collection of trading networks of the greatest historical importance, since they crossed the Eurasian continent from the Mediterranean to China. Silk was first imported into the Roman world in the first century BC, and for hundreds of years remained a luxury whose origins were not properly understood, until finally silkworm eggs were smuggled to Constantinople in the time of Justinian, in the 6th century AD. China was indeed known as Serica, the land of silk, and the north Chinese as Seres (the south Chinese were called Sinae, the origin of the word Sinology).

One reason that the source of silk could remain mysterious for so long was that the immensely long journey would typically be made in stages by different groups of traders, passing goods of all kinds from one to another; it was far more unusual for a single man to complete the whole transcontinental journey, like Marco Polo in the late 13th century, in the time of Kublai Khan.

The Mongol invasions earlier in the century had brought the world of the Silk Road even closer, since a Mongol dynasty was simultaneously ruling in China as the Yuan Dynasty and in Persia as the Mongol Dynasty or the Ilkhanate, until the subsequent conquests of Tamberlaine. But broadly speaking the western part of the route, up to the Taklamakan Desert, belonged to the Persian cultural sphere – passing through such legendary cities as Bukhara, Samarkand and Dushanbe – while on the other side began the world of Chinese culture. The exchanges that took place along this road, over a couple of thousand years or more, were thus not limited to goods and merchandise; it was a conduit for peoples and civilisations, languages, arts, ideas and religions.

In spite of the extraordinary significance of this line of communication across the most important continent for the history of human civilisation, the road itself was not named, it seems, until some point in the 19th century. It became particularly famous, no doubt, as a result of the exploratory and archaeological expeditions of Sir Aurel Stein in the first quarter of the 20th century; his greatest discovery was the Mogao Caves in Dunhuang, at the Chinese end of the road, one of which was filled with over 70,000 Buddhist and other manuscripts that reflected the diversity of religious traditions, extending even to Christian and Jewish texts.

The Silk Road – with a focus on the period 500-1000AD – is the subject of an outstanding exhibition currently showing at the British Museum; it has been described by one specialist in the field as among “the most ambitious and spectacular exhibitions ever staged at the British Museum”.

I shall have to discuss it, unfortunately, on the basis of the catalogue, but this is an impressive volume which contains a wealth of new scholarship and the discussion of many remarkable artefacts.

The main originality of the British Museum exhibition – anticipated in its plural title, Silk Roads – is to argue that the phenomenon was far more complex than we may imagine: not so much a single transcontinental highway as a network of roads spreading broadly and deeply into both the eastern and western parts of the continent. The main story is still of cultural exchange across Eurasia, but now that narrative is examined more closely within the different environments at each end of the route. The exhibition unfolds through six sections, from “Three Capitals in East Asia” to “Northwest Europe”, in the process introducing us not only to both material goods and intangible cultural exchanges, but also to different peoples, geographies and modes of transport.

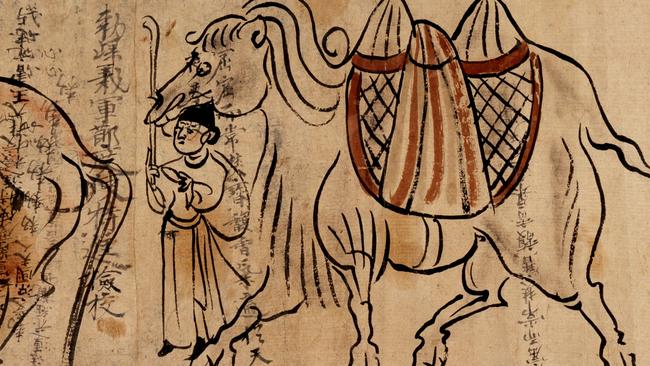

The first section starts with Japan, Korea and China; in 8th-century Nara, the emperor had a collection of exotic objects, including glass and metal wares from the Mediterranean and Persianate worlds; after his death, his widow dedicated his most treasured pieces to the Buddhist Todai-ji Temple, where remarkably they survive in the original 8th-century storehouse. Buddhism itself had migrated from India along the Silk Roads, with the anthropomorphic iconography that had arisen from Greco-Indian fusion in Gandhara, in the first and second centuries AD. In Tang Dynasty China, the capital Chang’an (close to modern Xi’an) was at the eastern end of the main Silk Road and was an extraordinarily diverse city, filled with Buddhist, Taoist and Zoroastrian temples and even a Christian church. When the last Sasanian king of Persia Yazdegerd III was murdered during the Arab invasion in the 7th century, his son Firuz and his entourage came to live in Chang’an.

A new discovery sheds additional light on maritime trade in this period: in 1998 a shipwreck was found off the island of Belitung near Sumatra in Indonesia: it had been carrying over 60,000 pieces of Tang Dynasty ceramics on a return voyage to Arabia or the Persian Gulf. The ship was of a type still built until modern times in Oman, and in 2010 a replica was made and successfully sailed from Muscat in Oman to Singapore, where it is now on display in the Maritime Museum. The story of the ship thus leads naturally to the second section, beginning with the early civilisations that arose in Southeast Asia under the influence of India and its great religions Hinduism and Buddhism; the most important ancient monument in our region and the largest Buddhist site in the world is still Borobodur in Java.

From Southeast Asia, this section then moves up to Tibet and to the Dunhuang caves already mentioned, particularly to the famous Cave 17 discovered by Stein, which had been filled with tens of thousands of manuscripts and then sealed up, whether to protect them from barbarian invasions or to entomb them as “sacred waste”, i.e. material no longer used but too holy to burn or simply discard. These documents reveal a fascinating world in which ideas and beliefs were exchanged and in which merchants and monks alike moved constantly between different languages: the migration of Buddhism to the east entailed the translation of Sanskrit and Pali texts into Chinese, and the exhibition includes a copy of a famous Buddhist sutra in alternating lines of Sanskrit letters and Chinese characters. At a more mundane level are glossaries and phrasebooks for travellers, like a Sino-Tibetan handbook that appears to have been written by a Tibetan, listing basic expressions in Chinese. This section ends with a discussion of the Uyghurs, a Turkic people now subject to systematic oppression in the west of China but once a considerable power in their own right.

After the Arab conquest of the Persian Sasanian empire in the 8th century, Arab forces confronted and defeated the armies of the Tang dynasty, which had extended its reach as far as Transoxiana; following this defeat, the Chinese withdrew largely to the east, allowing Uyghurs, originally from Mongolia, to take power over a vast area of central Asia. The authority of the caliphate too soon waned in its eastern regions, encouraging the regrowth of Persian culture in Khorasan, where the great national poet Ferdowsi composed his epic Shahname around a millennium ago. The Uyghurs, meanwhile, adopted the Manichaean religion which had originated in Persia and saw the world as a battle between the forces of light and darkness; such beliefs had a profound influence on many early Christians too, leading to the Monophysite heresy.

From the Uyghurs, the next section deals with the Sogdians, an Iranian people who were among the most important traders along the Silk Road, at various times more or less subject to Turkic, Chinese or other Iranian empires. They were Zoroastrians like the Persians, and there is an ossuary that shows priests, with their mouths veiled, attending the sacred fire, but they also worshipped a goddess called Nana. The next section expands on the people of the Central Asian steppe, and particularly the culture of the horse and the development of new forms of saddle and stirrups, as well as riding dress. Another short section deals with the Vikings who, even though they originated so far from the heart of the Silk Roads, were active in Central Europe, in Russia, Ukraine, the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, assimilating much from the cultures of the east.

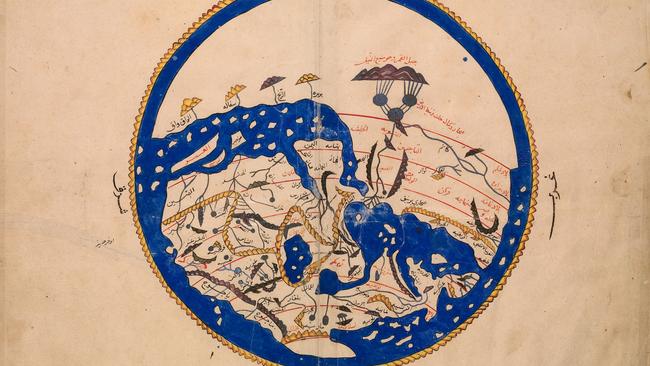

A longer section, Central Asia to Arabia, deals with Islamic civilisation, with its borrowings from Persia and Byzantium, as well as the re-assertion of Persian culture in the east under the Samanid Dynasty in Khorasan. Again the spread of learning is a fascinating subject, with the translation of Greek texts into Arabic, often by Persian scholars, as well as original texts. There is, for example a copy of the Compendium on calculation (originally written around 980) by the Persian polymath Al-Khwarizmi, whose Latinised name gave us the word “algorithm”.

The penultimate section, Mediterranean connections, takes us to Constantinople, the most important western terminus of this network of trade from the east, and to Egypt, one of the most valuable parts of the Byzantine empire until its conquest by the Arabs. In Cairo, the Ben Ezra Synagogue had its own “sacred waste” store, called a “geniza”, which survived until modern times; some 400,000 documents were sold to European and American libraries at the end of the 19th century and are still a treasure for researchers, including both scriptural and secular texts in the ancient and medieval languages of the middle east.

Northwest Europe, the final section, touches on the Carolingian world, but also on Anglo-Saxon Britain after the end of Roman imperial rule, arguing that far from becoming a backwater isolated from the restless dynamism of the Eurasian continent, Britain remained part of the astonishingly complex network that is evoked at the opening of the exhibition with a small copper alloy figure of the Buddha found in Sweden on the coast of the Baltic Sea.

Silk Roads.British Museum to February 23.

The Silk Roads catalogue by Sue Brunning et al, is available in Australia at various bookshops.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout