Obituary: Surrealist artist James Gleeson

JAMES Gleeson, who died in 2008 a month before his 93rd birthday, was one of Australia's most important and respected artists and our leading exponent of surrealism.

OBITUARYJames GleesonArtist. Born Hornsby, NSW, November 21, 1915. Died Northbridge, October 20, 2008, age 92.

JAMES Gleeson, who died in 2008 a month before his 93rd birthday, was one of Australia's most important and respected artists and our leading exponent of surrealism for more than half a century.

He was a prominent art critic for many years and the author of fundamental studies of William Dobell (1964) and Robert Klippel (1983), as well as a poet: his Selected Poems 1938-42 was published in 1993. Gleeson was also closely involved with forming the collections of the new National Gallery of Australia in the years leading to its opening in 1982.

Born in Sydney in 1915, Gleeson lost his father in the influenza epidemic of 1919; he was brought up by his mother, whom he later cared for until her death in 1958. He studied at the National Art School (East Sydney Technical College) from 1934-36, and then at the Sydney Teachers' College (1937-38), where he would later become a lecturer.

Though not directly exposed to the sufferings of the Depression, he was marked in his formative years by the political turmoil of the 1930s: the rise of fascism, the Spanish Civil War, the inexorable approach and then the reality of World War II.

He was drawn to surrealism as an artistic language capable of articulating the violence and unreason he saw overtaking the world; like many surrealists, he was also fascinated by the world of the unconscious mind revealed by Freud and Jung.

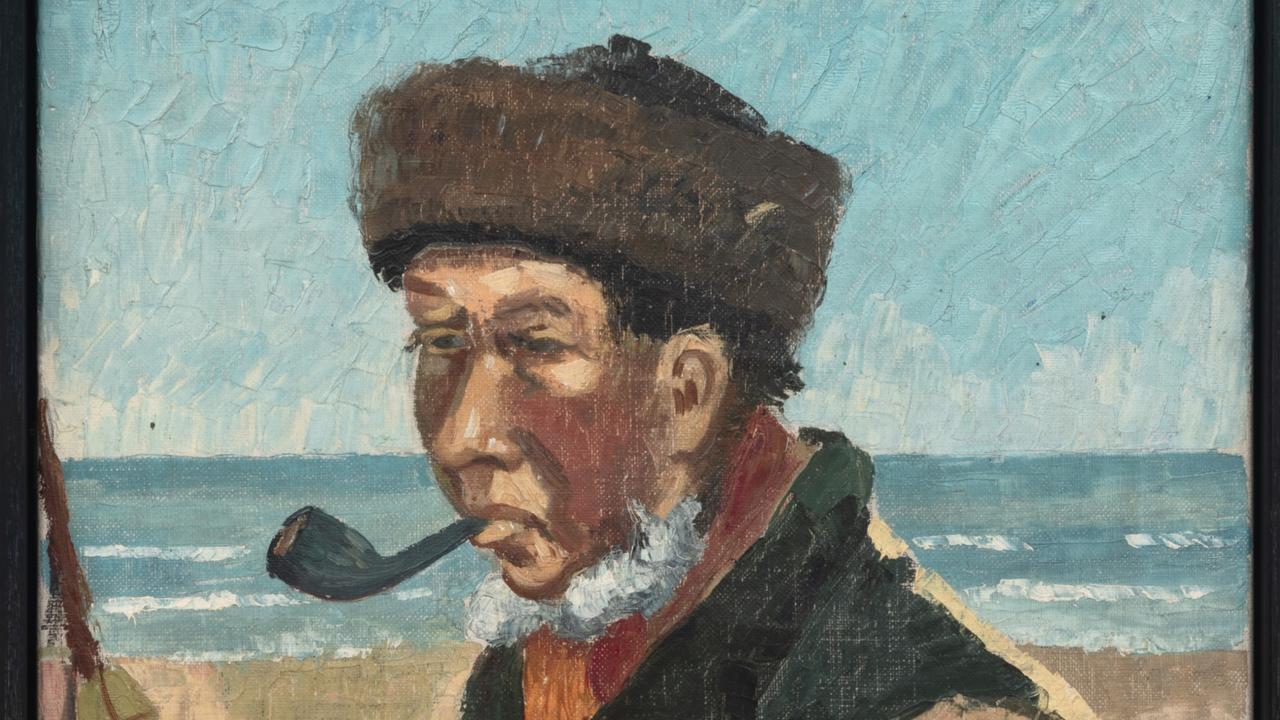

The earliest surviving picture by Gleeson is a copy of Lord Leighton's And the sea gave up the dead that were in it (1891-92), executed from a reproduction when he was 16 or 17.

This work poignantly evokes, as Renee Free has suggested in her monograph of Gleeson, the young man's longing for a lost father, but also anticipates the importance of the sea throughout the artist's work, as a source of life and of mysterious, sometimes sinister apparitions.

One of Gleeson's first significant works as a surrealist is indeed set on a beach: We inhabit the corrosive littoral of habit (1940), in which a man's features and a woman's naked torso dissolve, revealing the hollowness inside.

The idea remains something of a literary conceit, almost obviously an illustration of T.S. Eliot's poem The Hollow Men (1925), but a mature vision appears in the terrifying Citadel (1945), in which human features turn into a geological formation, and the hard mineral forms of teeth or shells grow out of the soft tissue of eyelids and lips.

Gleeson travelled to Europe in 1947-49, sharing a studio in London with Klippel, who became a lifelong friend. From there he proceeded to Italy, where the revelation of humanism and classicism turned him away from the grim vision of Citadel. For the next two decades he produced relatively few works, most of which were small and in a distinctive idiom combining elements of surrealism and symbolism with prominent male nudes that were rather closer to bodybuilders than to figures of the classical canon.

These were the years when Gleeson was kept busy writing and lecturing. In the '70s, he was appointed to many official positions, including the Commonwealth Art Advisory Board, then the Australia Council and most importantly the National Gallery of Australia, where he was chairman of the acquisitions committee in 1973.

There was little or no leisure time to paint, but Gleeson did find time to produce a very fine suite of collages, partly based on his youthful poems, and which in a sense represent a return to the sources of his inspiration as a surrealist.

After the opening of the National Gallery, Gleeson decided it was time to return to painting, and almost at once surprised the art world with a completely new kind of picture: large imaginary landscapes, set in the littoral zone that had always fascinated him, and executed with a rich painterly fluency.

There is the same uneasy juxtaposition that was foreshadowed in Citadel: hard mineral forms, like teeth, seem to grow out of slimy viscera or tender mucous membranes. These pictures could be construed either as visions of genesis or of apocalypse, but the tone is less of menace than of wonder at the sublime spectacle of life. One such composition, which included a fragmented self-portrait, surprisingly failed to win the 1994 Archibald Prize.

Although Gleeson often expressed deep pessimism about human nature, he was in person a gentle, charming and distinguished man, probably the most widely read and cultivated of Australian artists.

In 2006, he and his partner Frank O'Keefe (who died in January 2007) pledged all their assets (estimated to be eventually about $16 million) to a foundation intended to help the Art Gallery of NSW acquire significant works for the collection; this will be the most generous endowment the gallery has ever received.