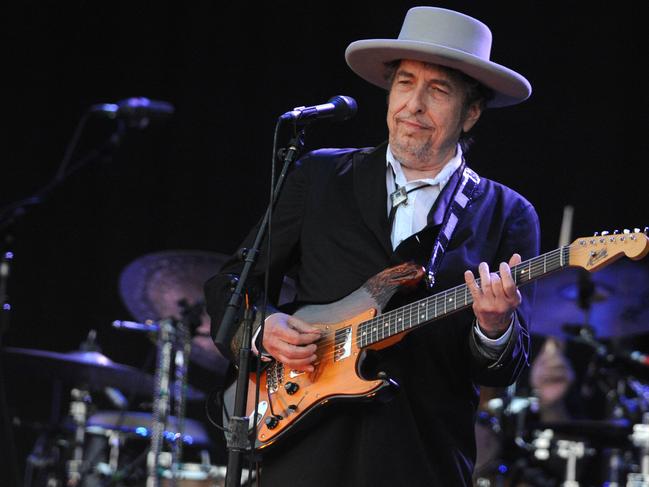

Bob Dylan offers an elegy to history and its shadow in literature

When I was a young man we thought we had our Shakespeare, and his name was Bob Dylan.

When I was a young man we thought we had our Shakespeare, and his name was Bob Dylan. Suddenly we had someone who sang and wrote songs who sounded like a great poet and a performer who was also an artistic genius.

Well, in 2016 the Nobel committee honoured that perception and it hangs over Dylan’s new album Rough and Rowdy Ways, in which that voice like a parody sounds velvet and sombre as Dylan offers his elegy to all things including the world of literature and history.

It’s a self-consciously artistic performance and the songs on Rough and Rowdy Ways constitute a rollcall of what has been said and what has been done, history and its shadow in literature.

Hearts are telltale hearts as in Edgar Allan Poe. Not what America can do for you but what you can do for America floats like a ghostly and ghastly cartoon of a quotation when the context is the assassination of president John F. Kennedy, who first came out with that injunction: we all know what America did for him, Dylan whispers, it killed him.

That song, the longest Dylan has recorded, was the first thing he has written to go straight to No 1 on the Billboard charts. It’s called Murder Most Foul and it’s an elegy for everyone, for Marilyn Monroe, who was JFK’s mistress, who famously sang happy birthday for him and died young. It finds a place for Lee Harvey Oswald, who took that shot, and Jack Ruby who shot Oswald. It’s a sort of funeral dirge for everything and everyone Dylan can remember. It’s a procession of history and remembrance into the grave. It’s very pensive, it’s beautifully accompanied, it’s very velvet. And what poet Robert Lowell described 50 years ago as Dylan’s “Caruso” voice is poignant and plangent as the great songwriter who has always seemed something more takes a bath in the culture he has been central to for so long.

These new, very deliberately “late” songs that make up Dylan’s first album in three years are full of allusions and innuendos in the echo chamber of history.

The Mother of Muses invoked in the title of one song is a mother of mercy to be found in mosques and monasteries. The Black Rider in another song is that sinister figure from an expressionist landscape and the opening track bookends the Shakespeare reference of the last one. The title and refrain “I contain multitudes” is one of the most famous utterances of Walt Whitman, who dislocated modern poetry into a new idiom, as you can argue Dylan’s did.

It’s all supersaturated with art, a bit beyond belief. But the Dylan who turned everything around in his 20s was a different character. On his second LP, Freewheelin’, the first fully original one, he narrates a song, a racketing boyish bluesy number with cheeky bits on the harmonica in which President Kennedy calls him up and asks him what we need to make the country grow and Dylan answers, “Brigitte Bardot, Anita Ekberg”.

Then, only a few years later, there’s that extraordinary song that took up the whole last vinyl side of the two-disc masterpiece Blonde on Blonde: Sad-Eyed Lady of the Lowlands.

This is the Dylan who knows all about the magic of what electric effects can do and who sings in a New York accent and has made war against Andy Warhol. But this is also the great artist of Mr Tambourine Man and Desolation Row in the most plangently elegiac mode imaginable.

Before we knew anything about Dylan’s life and the dedicatee being his wife Sarah we used to read the Kennedy assassination into this song. We took the words “And your magazine husband who one day just had to go” as the most mournful of ironies because we imagined the subject of the song to be Jackie Kennedy because she mourned for a world that was cut down. She symbolised and became emblematic of a world of sad eyes. Sad-Eyed Lady of the Lowlands is one of the greater songs ever written as Murder Most Foul simply is not. And that’s true of so many of those rich inflamed heartbreaks of songs that Dylan recorded mainly between 1962 and 1967.

He wasn’t really a protest singer for long, it’s simply that songs such as The Times They are a-Changin’ are carved on the gravestone of America. Think of The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll, about a black woman murdered by a southern gent: “Oh, but you who philosophize disgrace and criticize all fears / Bury the rag deep in your face / For now’s is the time for your tears”.

Not rationalise but philosophise with its depths and profundity of betrayal.

Only the young Dylan could have written a song of infinite aching desolation and sing “When your gravity fails and negativity don’t pull you through”. With his howling broken parody of a voice he took the actual idioms of an educated, spoiled, drug-happy and forlorn generation, a middle-class generation that gazed in appal at the Vietnam war and made that idiom into a comprehensive argot that seemed Shakespearean because he could say anything in it.

He could sing to a girl who he said was “just like a woman” that “I was hungry and it was your world”. And he could rage in post-erotic lament. “It ain’t me you’re looking for, babe.” Negativity might not have pulled him through but he brought to it an extraordinary power of blackness (“You’ve got a lot of nerve to say you are my friend”) just as he could write the most skipping lyrical bursts of music like Tambourine Man, where the melody seems to hang on the air with an unearthliness that is matched by the dense, sparkling symbolistic lyrics. He could write about a lover who spoke like silence without ideals or violence. No one had written songs like that before.

He turned himself into a bard and then for the next 55 years he has survived in his grand, distinguished way, on the afterglow. Blood on the Tracks in 1975is a great album but not one of his greatest. Nor is Rough and Rowdy Ways — an album that is neither of those things — but it will mesmerise anyone who has ever fallen for this writer and singer of songs who reinvented the world.

It took me years to make my way to Mozart and Wagner.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout