Rolling Thunder Revue: revisiting Dylan’s masterpiece

The first leg of the Rolling Thunder Revue in 1975 was Bob Dylan’s finest hour onstage, a tour without precedent.

In 1975, everything came together for Bob Dylan.

The first leg of the Rolling Thunder Revue was his finest hour onstage, a tour without precedent that brought a crazy, cosmic road show to a small theatre near you on extremely short notice: 31 shows in 23 cities across northeastern US, from October 30 to December 8. Dylan, liberated by the freewheelin’ format, gave some of the most dynamic and dramatic performances of his career, spurred on by the thrilling arrangements of an intuitive band.

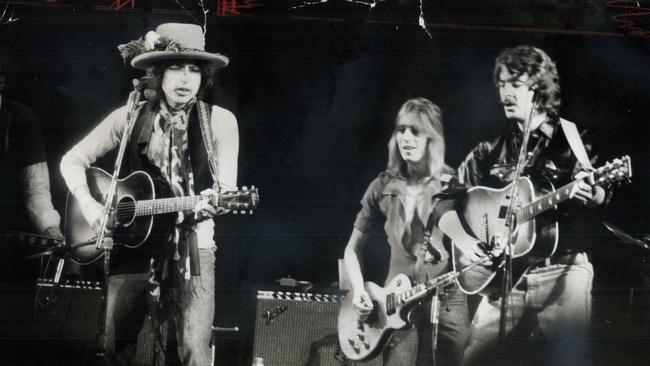

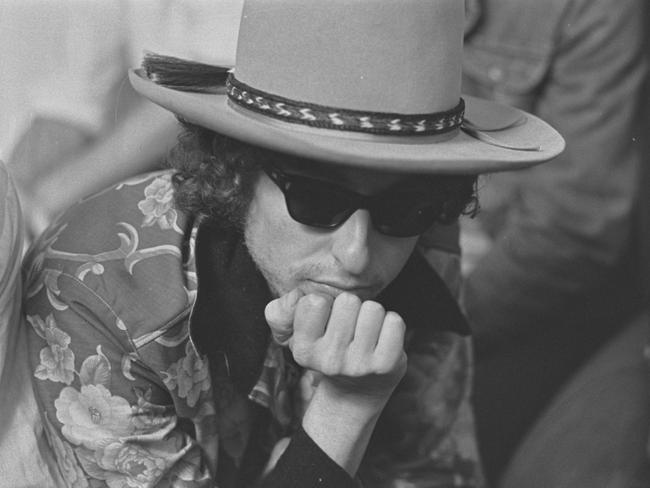

These concerts, seen either live or through the lenses of photographer Ken Regan and cinematographers Dave Meyers and Howard Alk — and now featured in Martin Scorsese’s Rolling Thunder Revue: A Bob Dylan Story on Netflix — leave us with an indelible image of Dylan the performer: the white-faced gypsy, wide-brimmed hat decked with fresh flowers, Indian scarf, black vest over tie-dye Henley shirt, walking the high wire, wringing meaning from every last syllable.

The tour’s success can be condensed to a simple fact: Dylan had taken back control of his art. Working without a manager at the time, he delegated tasks (stage direction, musical direction, tour management) to trusted friends and collaborators, leaving him room to manoeuvre. The revue format also shifted the focus away from him and on to fellow performers, a long-time goal, and his embrace of the ensuing chaos was total. Everyone had a piece of the puzzle, but only Dylan, calm in the eye of the hurricane, had it all.

The idea for this raggle-taggle caravan, its vaudeville vibe and newsworthy guerilla tactics (word-of-mouth promotion, pop-up shows and in-house ticketing, in which Dylan seems to have been something of an American trendsetter) had its roots partly in dissatisfaction with the previous year’s exalted but exhausting comeback tour with the Band, after an eight-year stretch of no tours (and only one short full-length show on the Isle of Wight). He’d been away longer than the length of his previous career and, because his return was a bigger deal than his performance, Tour 74 became a chore. “I wasn’t comfortable and I wasn’t happy,” Dylan remembered. “I wanted to do something different.” This required an entirely different philosophy and aesthetic, a different way of travelling; perhaps even a different type of song.

Dylan didn’t tour Blood on the Tracks, released in January 1975, the album that saw him reclaim his title as heavyweight champion of the world. Instead, for six weeks that northern spring, he played hooky in the south of France. On May 24, his 34th birthday, Dylan went to a festival in Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer, where a pilgrimage of thousands of gypsies had congregated to venerate their patron saint, Black Sara.

There he saw the procession carry Sara’s statue from the church to the sea; he also met a man “with 12 wives and a hundred children” who described himself as “the King of the Gypsies”. This inspired a new song from Dylan, One More Cup of Coffee, its gypsy-inflected mood perhaps setting the tone for all that was to follow.

Desire — most of which was recorded over two nights in the summer of 1975 — wouldn’t come out until the following year, after this first leg of the tour was done, but Dylan was keen to hit the road to debut this new, unreleased material, particularly Hurricane, a cinematic protest song about Rubin “Hurricane” Carter, the boxer falsely imprisoned for murder whose memoir Dylan had read in France. And he had a vision: a tour that would last forever. He fantasised that he could “just join the tour for a couple of weeks and then leave”, that someone else could take over. He’d be the main thing, but not the only thing. It was all of a piece with his inspiration: nomads on the road hacking the system, turning up unexpectedly at small halls, and perhaps some bigger rooms to foot the bill.

Dylan knew the road show had to be autonomous and self-financing, creating room for spontaneity and chaos, where Dylan’s art had always thrived. He wanted to make a movie too, but he knew he couldn’t make the film he wanted within the Hollywood paradigm. They’d do everything themselves.

The theatrical show he had in mind couldn’t be thrown together; it required planning and stage direction. And despite the fact that rehearsals in Manhattan seemed haphazard, the final arrangements were the result of hard work: the way the solos build in It Ain’t Me Babe — Mick Ronson’s wheedling bluesy riffage crossfading into the thrilling chime of David Mansfield’s arpeggiated steel before Dylan’s climactic hip harp — doesn’t happen by chance. Dylan was working as he always has, playing through the songs and letting the musicians find their place in the overall tapestry. This approach might not always work, but when it does, the sublime is within reach. In 1975 Dylan’s intuition was uncanny.

And off they went, making up the rules as they went along, in a 70-strong travelling party including a film crew of 15 and Dylan’s beagle, Peggy. Their convoy included two tour buses (one rented from Frank Zappa), a Winnebago (“The Executive”) often driven by Dylan, and a red Cadillac.

■ ■ ■

A Bob Dylan tour was itself already headline news, but the biggest draw may have been Dylan’s reunion with Joan Baez: they hadn’t been seen onstage together since 1964. Now she was given star billing, which she repaid with superlative performances. As if this alchemical remarriage of the king and queen of 60s folk wasn’t enough to whet the appetite, news soon emerged of famous friends playing unscheduled mini-sets: Joni Mitchell, who came aboard in New Haven and never left, Gordon Lightfoot in Toronto, Arlo Guthrie, Rick Danko, Ronnie Hawkins and Robbie Robertson — the audience must have felt it was at the centre of the world. Leonard Cohen showed up at the Montreal show but modestly demurred from playing. Others, like Bruce Springsteen and Patti Smith, came only to take it all in. Allen Ginsberg was along for the ride too, representing the Beat heritage, but, perhaps surprisingly, didn’t Howl, only tinkling finger cymbals at various finales.

The Rolling Thunder Revue was about much more than the 20 songs Dylan played, whether solo, with Baez, with the smaller Desire combo or with the larger assemblage of musicians that included bassist Rob Stoner, the future musical director and glue of the Rolling Thunder band, which came to be known as Guam.

The revue was an umbrella under which many could shelter from the storm, its format allowing for lots of moving parts and last-minute additions, though the structure was always precisely the same and Dylan’s song choices were unusually consistent.

The theatre director Jacques Levy plotted a show as theatrical as the songs. A large Persian rug covered the stage, with a long runner along the very front beneath the microphones, while a canvas painted in the style of a medicine show was used either as a front curtain or, in smaller venues, a backdrop.

The role of master of ceremonies fell to Bob Neuwirth, who first welcomed the audience to the “Rolling Thunder living room”, and introduced Guam generally, then individually, as each band member stepped forth to sing a song, ranging from an unknown T Bone Burnett’s cover of Warren Zevon’s equally unknown Werewolves of London to Ronee Blakley’s show-stopping Need a New Sun Rising.

The first big cheer of the night was reserved for Neuwirth’s version of Mercedes Benz, made famous by his co-author, Janis Joplin. His set segued into Ramblin’ Jack Elliott’s, which always led directly into Dylan’s first appearance.

The development of Dylan’s opening portion of the show over the tour is evidence that he was in his element. What started as five songs (When I Paint My Masterpiece, It Ain’t Me Babe, A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall, Romance in Durango and Isis) became six by the middle of the tour (the addition of The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll as an alternative to Hard Rain, and It Takes a Lot to Laugh, It Takes a Train to Cry).

By the end, it had swelled to seven, incorporating a rewrite of Tonight I’ll Be Staying Here with You (now including the pertinent lyric “You come on to me like Rolling Thunder!”).

The set reached its crescendo with the materialisation of violinist Scarlet Rivera for the last two songs. With her arrived a brand new Dylan sound — the sound of Desire amplified. Her sawing, swooping, soaring playing over the band’s tightrope arrangements, and Dylan’s feverish delivery, pushed the first half of the show to the edge of madness.

The band’s version of Isis brought out a Dylan unlike any other: guitarless, fists clenched, wrists crossed, eyes wide, veins bulging with the effort of delivery, fingers fluttering, his movement such that the whiteface is Marcel Marceau’s. It’s the greatest Dylan has ever sounded. After a swift “We’ll be back in 15 minutes,” the curtain fell, giving the audience a moment to catch its breath, to consider what it had just witnessed.

■ ■ ■

When things are working for Dylan, the presentation is an effortless part of the whole, understood to be part of its meaning and message.

This was never truer than on this tour: everything coheres.

At the end of intermission, Dylan and Baez opened the second half of the show in darkness, singing the first song unseen behind a curtain that wasn’t raised until they were halfway through the second verse, a slow, chilling reveal. There they were, together again in the pinprick of the spotlight, playing not only songs that made them famous in the 60s (and the 60s famous), but covers and folk favourites. Their set climaxed in I Shall Be Released, before Baez performed on her own.

This sequence must have been judged an immediate success, since the song line-up changed only slightly.

After the frenzy of the first set and the bonhomie of the duets with Baez, Dylan reined it in with the intense intimacy of a solo song, after which he was joined by the core Desire band to showcase four songs delivered with astonishing focus, all from the still unheard record: Oh, Sister, Hurricane, One More Cup of Coffee and Sara. The last song went hand in glove with the next, a theatrical, aching Just Like a Woman.

This segued into Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door, on which McGuinn helped Dylan pack up the tents by singing a verse, before a victorious Baez-led clap-along finale of This Land is Your Land, a final flourish of the fedora to Woody Guthrie. And curtain. Such a spectacle allows no encore.

■ ■ ■

The second half of the Rolling Thunder Revue, which didn’t properly launch until April 1976 in Florida, was quite different in everything but name: the euphoric devil-may-care spirit of the first leg was never rekindled. Personnel changes made life less cordial, and though the same core band remained, the pristine earlier arrangements were ditched. In fact, almost all the Desire material disappeared, despite the fact that the new album had just spent three weeks at No 1. After the second Night of the Hurricane show in Houston, at which it presumably could not be avoided, the song Hurricane was never performed again. Dylan had moved on.

The look was revamped too; Dylan was now an unshaven and careworn Delacroix beneath a Bedouin headdress.

The power and intensity of performance still raged, but the aesthetic was completely new: darker and edgier, ragged and dirtier. Dylan had bottled lightning on that first leg; its free-spirited art-for-art’s-sake philosophy couldn’t be sustained and perhaps wasn’t meant to over longer distances, through larger arenas in less hospitable territory, where there was once more a bottom line, an obligation, a debt.

The stakes were higher; it was back to show business with the executives and accountants.

Nowadays many attempt their own Rolling Thunder, but this was the first and the best. For one glorious autumn, it all came together, thus proving again a poem I heard once upon a time, which I paraphrase from memory since I can find no trace of it anywhere: “You do it once, you do it for fun; you do it again, and then you’re done.”

The Wall Street Journal

Wesley Stace is a novelist and musician. This essay has been abridged and adapted from his liner notes for the box set The Rolling Thunder Revue: The 1975 Live Recordings.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout