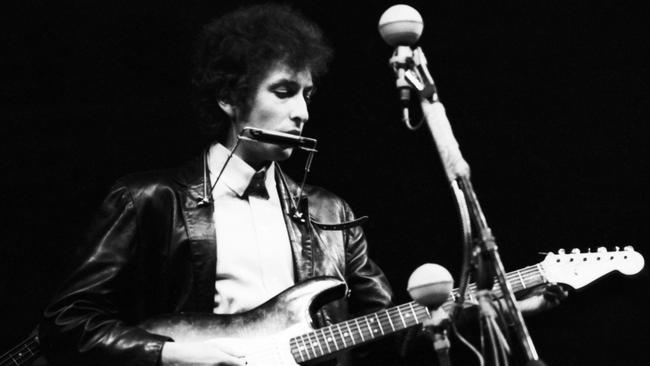

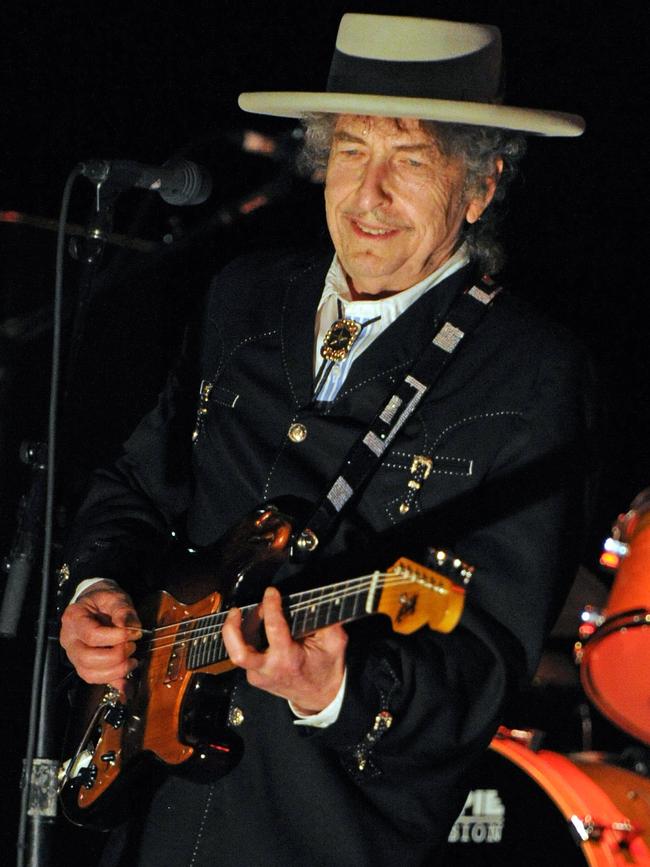

Bob Dylan, Australian tour: songs, film, sculpture, a life in art

On the eve of Bob Dylan’s latest Australian tour, we review the full range of his artistic output.

Can Jack Fate save the world? The once legendary singer has been sprung from jail to perform in a benefit concert that will be internationally televised from a nation racked by war. It’s never made entirely clear who exactly the performance will benefit, nor why Fate was incarcerated, despite being the offspring of the country’s military dictator.

There are some exquisite rehearsals along the way — luckily for Jack, he is introduced to a tribute band called Simple Twist of Fate — but the concert never transpires. Jack is rearrested after a journalist is beaten to death with Blind Lemon’s guitar. He is transported back to jail to the tune of Blowin’ in the Wind.

The scenario belongs to Masked and Anonymous, Larry Charles’s first directorial effort 15 years ago, in which he shares scriptwriting credits with a certain Sergei Petrov. The latter, better known as Bob Dylan, also has the star role — alongside John Goodman, Jeff Bridges, Jessica Lange and Penelope Cruz, all of whom reputedly settled for below-par wages for the opportunity.

It was one of Dylan’s detours, yet another leap into the unknown. More broadly, it’s a tactic he has diligently practised since the early 1960s, apparently without knowing exactly where he was going to end up. There have been other movies along the way, including Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid back in 1973, in which he played taciturn sidekick Alias to Kris Kristofferson’s Billy, and composed a soundtrack that yielded Knocking on Heaven’s Door.

Lay Lady Lay was commissioned for Midnight Cowboy, but Dylan was late in supplying it, so the producers chose Harry Nilsson’s Everybody’s Talkin’ instead. Then there was Renaldo and Clara, filmed during the Rolling Thunder Revue of 1975-76; the four-hour movie’s dramatic sequences, featuring Joan Baez, Sara Dylan and Allen Ginsberg among others, remain shrouded in ambiguity but the concert footage is exquisite and may turn up at some point on a long-rumoured Bootleg Series video.

Somewhat bizarre movies constitute just one of Dylan’s divertissements, mind you. He also has dabbled in the fine arts, from iron sculptures to landscape paintings. He attributes the metallic obsession to his upbringing in the Minnesota iron-mining towns Hibbing and Duluth, whose fate he brilliantly articulated in North Country Blues.

The artwork has a longer trajectory. Back when a compendium of his lyrics, poems and liner notes was first published in the early 1970s, titled Writings & Drawings, it contained a number of cartoonish sketches comparable with the artwork of Woody Guthrie and John Lennon. In recent years, though, considerably more sophisticated landscapes — weighted in favour of lonesome highways — have been exhibited. So have his heavy metal works, notably wrought-iron gates that he said five years ago “appeal to me because of the negative space they allow. They can be closed but at the same time they allow the seasons and breezes to enter and flow. They can shut you out or shut you in. And in some ways there is no difference.”

The Dylan enigma is clearly not restricted to his lyrics. Back in 1965, when asked if he were to sell out, which commercial interest he would choose, Dylan offered an apparently facetious two-word response: “Ladies’ garments.” Three decades later he appeared in an advertisement for Victoria’s Secret — and was accused all over again of selling out.

Arguably even less likely was his foray into liquor production, given rumours of struggles with alcohol over the decades. Earlier this year, three types of Heaven’s Door whiskey surfaced in the US, with the rye variety in particular receiving plaudits from connoisseurs.

Perhaps the most fruitful of his side projects was Theme Time Radio Hour, launched a dozen years ago, in which the Bobster provided a deliciously wry commentary to an eclectic bunch of tracks chosen on the basis of weekly topics that ranged from the weather to pets and politics. The 101 shows recorded across three years are a veritable cultural goldmine, featuring unimaginably obscure songs alongside better-known tunes from across the ages.

So, what next? In Dylan’s case, who knows?

For the moment, in the 31st year of his Never-Ending Tour, he returns to Australia next month for the 11th time since 1966, apparently determined to keep on keepin’ on, even as contemporaries such as Baez and Paul Simon are calling it a day with, respectively, their Fare Thee Well and Homeward Bound tours.

It is perfectly possible that the Theme Time experience played a role in Dylan’s decision to delve into the Great American Songbook. His studio output in recent years has been restricted to tunes associated with the likes of Frank Sinatra and Billie Holiday. He clearly does not have a voice to match, though — it went awry at the cusp of the 1990s — and the five discs he has released in the genre, across three albums, reflect a familiar career trough.

On the other hand, his unexpected folk recordings Good as I Been to You (1992) and World Gone Wrong (1993) sounded disappointing at the time but, like a good whiskey, seem to have matured over the years. As Time Goes By may sound ridiculous in Dylan’s voice, but that verdict may need to be reassessed at some point in the future.

It’s hard to disagree, though, with Patti Smith who, when asked in a recent Mojo magazine interview whether she thought it was ironic that Dylan had received the 2016 Nobel Prize in Literature when “he was releasing nothing but Frank Sinatra covers”, responded: “If I want to listen to Sinatra, I’ll listen to Sinatra. But I look at Bob Dylan the same way I look at Picasso. Guernica is the most important painting ever. I love cubism. But if he wants to do 45 fish plates, he can, because he’s Picasso.

“I took that attitude with Bob a long time ago. It’s been a very long time since I’ve related to some of the things he’s doing. But it doesn’t matter, because I can go back, when I’m in a certain mood, and listen to Chimes of Freedom or John Wesley Harding.”

Dylan’s past is indeed packed with miracles and revelations, some of which have come to light relatively recently, courtesy of the ongoing Bootleg Series project launched in 1991. The high points crept in almost immediately after his self-titled Columbia debut in 1961.

His second and third albums, The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan and The Times They Are A-Changin’, consisting almost exclusively of original compositions, signalled an unprecedented talent. Bringing It All Back Home, Highway 61 and Blonde on Blonde confirmed the suspicion that his genius was also unparalleled. The motorcycle accident that followed an agonising 1966 international tour, during which folk-rock innovation alongside his backing band the Hawks was frequently greeted with boos, catalysed a reinvention that sowed the seeds of Americana. Had the mishap spelled the end, Dylan’s status as a cultural avatar would nonetheless have endured.

Instead, he returned with one of his finest acoustic albums, John Wesley Harding, and then turned up, with the Hawks — subsequently rechristened as the Band — in tow, for a scintillating performance at the Woody Guthrie memorial concert in New York 50 years ago. The bunch of albums that followed tended to be derided until Dylan returned to the stage, initially with the Band and subsequently with a bunch of confreres ranging from Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, Baez and beat poet Ginsberg to Roger McGuinn, with occasional appearances by the likes of Joni Mitchell.

The mid-70s Rolling Thunder Revue was a career peak, embellished with a pair of unsurpassed studio albums, Blood on the Tracks and Desire, the latter featuring Emmylou Harris on backing vocals. The former provides the basis for the rumoured forthcoming release of More Blood, More Tracks as part of the Bootleg Series.

Dylan aficionados are well aware that expecting the unexpected is par for the course. Several years after his declaration of independence from the new and the old left, Dylan released a track in 1971 dedicated to George Jackson, a radical African-American activist shot dead while trying to escape from prison. “Sometimes I think this whole world / Is one big prison yard,” he declares. “Some of us are prisoners / The rest of us are guards.” Like many of his early songs, it still rings true.

That same year he put in a memorable performance at George Harrison and Ravi Shankar’s Concert for Bangladesh. And in 1974 he helped to sell out An Evening with Allende, an event co-ordinated by his old frenemy Phil Ochs as a benefit for Chilean refugees from the fascist Pinochet coup. Not long afterwards, he picked up cudgels on behalf of middleweight boxer Rubin “The Hurricane” Carter, who had been sentenced on a murder charge.

There have been some worthy recordings since then, but fairly dispensable albums as well, although even the most risible ones invariably contain a gem or two. There have also been some remarkable interventions along the way, including a performance of the timeless The Times They Are A-Changin’ at the Obama White House during a 2010 event celebrating the songs of the civil rights movement (almost half a century after he sang Only a Pawn in Their Game at the 1963 March on Washington), and a version of Guthrie’s Do Re Mi contributed to The People Speak project, which sprang from socialist historian Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of the United States.

More recently, when approached to contribute a track to a mini-album celebrating gay love, Dylan not only immediately agreed but also knew right away which song he would perform. Universal Love, released in April, opens with his touching version of He’s Funny That Way.

Thirty years ago, meanwhile, there was the accidental birth of a supergroup called the Traveling Wilburys, which featured Dylan alongside Harrison, Roy Orbison, Jeff Lynne and Tom Petty and led to a pair of disparate albums. There were tours with the Grateful Dead — yielding a distressing live album, as well as an application for formal membership of the band, which enthused Jerry Garcia but was vetoed by Phil Lesh — and Petty and the Heartbreakers. More recently, Dylan fulfilled one more ambition with a ludicrous Christmas album.

His literary endeavours have been restricted to a largely incomprehensible stream-of-consciousness “novel” titled Tarantula in the mid-60s and, almost 40 years later, a beautifully written, though highly selective, memoir, Chronicles: Volume One. A second volume is scheduled for publication late next year.

It was his songbook, though, that earned him the Nobel, which Leonard Cohen graciously compared to pinning a medal on Everest for being the highest mountain.

Dylan seemed ambivalent about the award, taking his time to acknowledge it, and even longer to deliver the obligatory Nobel lecture, in which he traces the trajectory of his themes back to ancient Greece then declares that what songs mean matters less than how much they move you, adding for good measure that lyrics are not literature and concluding with a quotation from Homer: “Sing in me, O Muse, and through me tell the story.”

That seems an apt way of summing up one of the more remarkable storytellers of our times. There is no saying how long the ghost of electricity will continue to howl in the bones of his face, but as long as it doesn’t short-circuit, his live performances will continue to deliver a charge, even if its intensity may vary from one night to the next.

Bob Dylan’s Australian tour opens in Perth on August 8, followed by Adelaide, Melbourne, Sydney, Wollongong, Newcastle and Brisbane.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout