Artists and models

This is really an excuse to display a selection of prints and drawings with some other material, under a theme that is appealing and, as it turns out, timely.

LOVE, Loss and Intimacy, at the National Gallery of Victoria, is a thematic exhibition that is really an excuse to display a selection of prints and drawings from the collection with some other material, under a theme that is appealing and, as it turns out, timely; several drawings are by the pre-Raphaelite artists whose romantic adventures were the subject of a recent television series on the ABC.

A painting by William Orpen is set at the entrance, before we see anything else, as an introduction to the world we are about to enter. Night (1907) is a self-portrait of the artist with his wife. It is striking enough in reproduction, but much more so when you stand before the picture itself.

The artist represents himself standing behind his wife's chair. He leans down to kiss her; she throws her head back in an attitude of abandon, reaching up and pulling him down towards her with one hand.

What you really notice when standing before the painting is the immense space of the dark window, emphasised by the open curtains on either side.

It evokes two things simultaneously: the deep gulf of passion in such a relationship, and -- as the open window allows anyone outside to look in -- a certain sense of the exposure of their intimacy.

The gulf of passion is certainly what appears when you scratch the surface of the pre-Raphaelite drawings because all the models can be identified and each young woman turns out to be the object of several painters' erotic obsessions. Of course this was not the first era in which an artist's model was also a mistress or lover but, whereas models were originally used to study the figure, from the romantic period onwards they tend to be recognisable as individuals and even the object of a somewhat voyeuristic gaze.

Thus there is a pale and haunted Elizabeth Siddal drawn by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, intended as a St Catherine of Alexandria -- the saint who was meant to be torn apart on a spiked wheel and after whom the Catherine wheel is named -- and an intense but subtle head of Maria Zambaco posing as Psyche for Edward Burne-Jones, who was involved in a secret and passionate liaison with her at the time.

There is more objectivity in Burne-Jones's three studies of Antonia Cava, with whom he was presumably not in love, for here the face is only suggested, and the real subject of the studies is the anatomy of a girl coming down a staircase: the drawings are studies for his painting The Golden Stairs (1880), in which the faces were modelled on his daughter Margaret and several of her young friends.

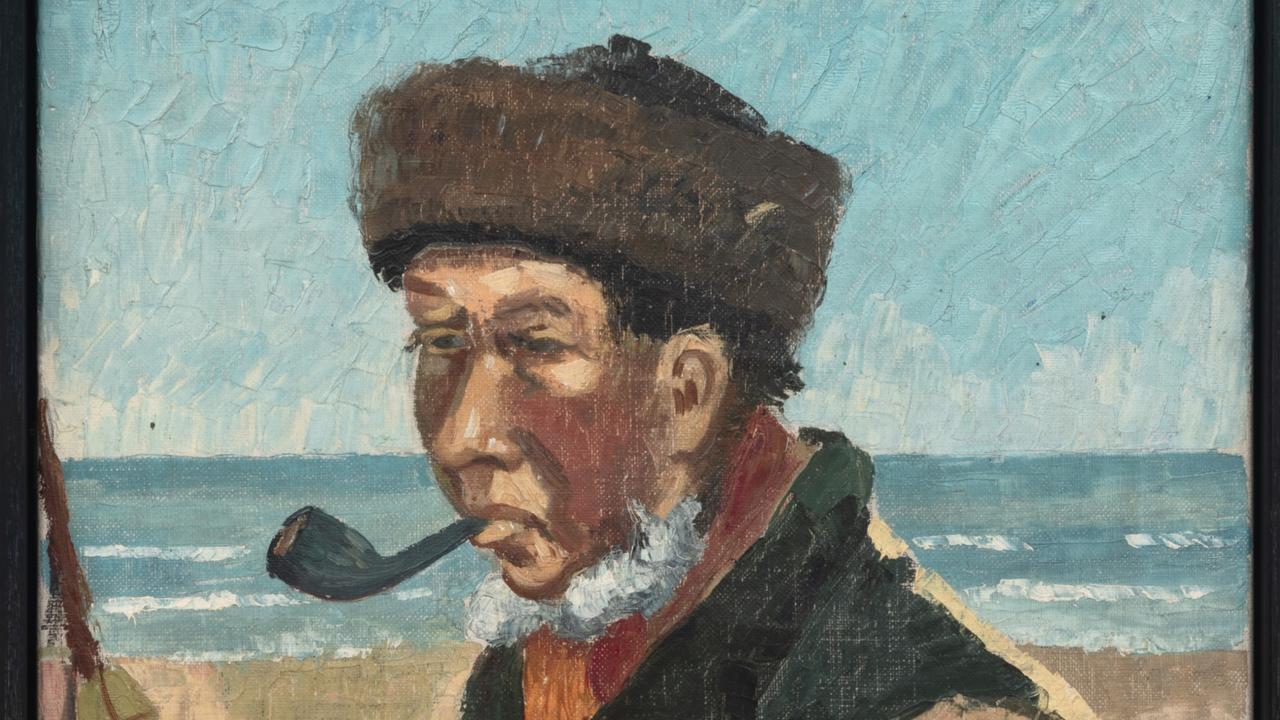

Augustus John was even more unconventional than the pre-Raphaelites, and much less worried about it. He managed to live and have children with several women at more or less the same time, and on the whole they all seemed to get on reasonably well; yet again we find that people a century ago could be more unconventional than we can imagine.

There is a remarkable tiny etched self-portrait by John that reminds us how talented he was, something not always apparent from his more facile or flamboyant work. Several images of his family, such as the beautiful little etching of his wife Ida and two children, Out on the Moor (1906) recall the paintings George Lambert did of his own family and his complicated domestic arrangements, in the same years.

Among other artists and their models, there is Jacob Epstein, whose wife also tolerated a series of relationships with model-mistresses, and even reared their children, as she could not have any herself. There is Picasso, too, with an etching from the Vollard Suite in which a sculptor models a figure while Marie-Therese Walter poses. In a brilliant metaphor, the artist and the sculpture are both drawn in outline only, while the figure of Marie-Therese, the object of his aesthetic (and erotic) attention, is fully developed with tonal hatching.

In fact this little exhibition could perhaps have been more appropriately or coherently built around the theme of the relationship between artist and model; this is by far the most striking and recurrent theme among the works on display. Perhaps it was originally less dominant but came increasingly to the fore as curatorial research revealed the complex stories behind what would seem, to the casual glance, merely life studies, sketches for larger paintings or small printed works.

There is an interesting line in this kind of historical research, and probably in all biographical approaches to artists or writers, between information that illuminates the work itself and gossip, or should we say, more kindly, biographical research for its own sake. It is not a border that one would wish to police too strictly, since if gossip can bring the art of the past to life for us, we are prepared to tolerate quantum sufficit, as they say in medical prescriptions, as much as is necessary.

It is notable, however, that the interest of information about the artists' love affairs is somehow in inverse proportion to the quality of the work. Thus the stories of the pre-Raphaelites and John, ultimately secondary artists, are engrossing; but when we find ourselves before Edvard Munch's more powerful woodcut, The Kiss, we are less concerned to learn about the painter and his mistress Millie; not that this is irrelevant to a deeper understanding of Munch as man and artist but just that this work stands on its own, and that its power as a poetic image is not increased by the information.

The rule is not universal. Among a beautiful set of works by Rembrandt is a little sheet of drawings in iron-gall ink of a young woman and a baby. It is important to know that the models are most likely his first wife, Saskia, and one of the several babies that she bore and sadly lost at a very young age.

Another work, a small etching, shows the artist and Saskia in the early days of their marriage, but it raises other curious questions. Rembrandt's arm, holding a writing instrument, frames the right-hand side of the composition. It looks like his left arm, but bearing in mind that a self-portrait is a mirror image, it must be his right.

If that seems straightforward, it isn't: an artist can't draw himself holding a pen or brush in his right hand unless he is left-handed, which Rembrandt clearly was not. What they often do in self-portraits is to pose holding the instrument in the left hand, which looks like the right in the mirror-image.

What we are witnessing here is actually a double reversal: Rembrandt would initially have made a silverpoint drawing of himself and Saskia with a mirror, holding the silverpoint in his left hand so that it seemed to be in his right in the drawing; but then in making an etching from this drawing, the image was reversed again, so that it appears as we now see it.

Also intriguing is the etching Woman Sitting Half-Dressed Beside a Stove (1658); apparently a life study in the studio, although the formal elegance of the pose strikes a more artificial note. If this image looks familiar, it is because it is a by-product of one of Rembrandt's most important paintings, the Bathsheba in the Louvre (1654).

The young woman has just received and read a letter from King David; she stares into space, dreaming of what this means -- not knowing that the king will arrange the death of her husband in battle, that they will marry and that she will become the mother of King Solomon.

The attitude of the figure is based on a minor ancient relief, engraved a few years earlier in a collection by Francois Perrier, the Icones et segmenta of 1645, which served as a kind of source book of antique inspiration. The relief was known as the Nova Nupta, the new bride, because she appeared to be a young girl being prepared for her bridal night by a servant, and covering her face in shame at the prospect.

Not only the form but the theme were perfectly suited to the story of Bathsheba, the young married woman who was destined to become, unexpectedly, a bride once again, marry one king and become the mother of another and, from the Christian point of view, turn out to be one of the ancestors of Christ.

What is particularly interesting about the 1658 etching is that it gives us a glimpse into the process of synthesis: what we see here is neither the model as herself, nor Bathsheba as a complete imaginary creation, but the model posing as Bathsheba and sitting by the stove, trying to keep warm on a cold night in Amsterdam while pretending to be a girl bathing on a rooftop in Jerusalem.

There are other things in this slightly disparate show, some of which are more relevant than others -- a video of Judith Wright's son sleeping by her and a series of drawings by Jon Cattapan of his father on his deathbed stand out. Particularly poignant is Max Klinger's drawing of his newborn child, fostered because the child's mother was preoccupied with her own self-realisation, as the catalogue rather hopefully puts it. (She later went mad and spent the rest of her life in an asylum.)

Although the drawing of the infant is not beautiful in itself, it is an attempt to hold on to the memory of a child who will be taken away. More inherently touching are the small partial sketches on the same sheet -- cropped in reproduction in the floor brochure -- that convey the animation of the newborn baby. This, if anything, captures the exhibition's original inspiration: that where there is love, there is bound also to be the sadness of loss.