Inventive, despite the preaching

ADELAIDE can be an odd place.

ADELAIDE can be an odd place.

On the way from the airport a couple of days ago, I found myself seated near an obviously unstable woman who kept yelling to the bus driver to go faster, along with several other more or less drug-damaged or derelict types, before we were joined by a brawny individual who loudly harangued the passengers about the sufferings of the New Zealanders, compared with which those of Australians were negligible. A little later in a taxi, when, as a conversational banality, I expressed the hope that the summer heat would soon end, the driver replied "there's no end till you put a bullet in the brain, mate", and much more followed.

Surely that was enough loopiness for one day, but then I was confronted with Brenda Croft's introductory essay for Stop(the)Gap at the Samstag Museum: the essay is a disconnected and apparently improvised rant about Australia Day, the Northern Territory intervention and even the way Aboriginal art is judged by non-indigenous people. Chips on the shoulder don't come much bigger than the one displayed here and it does nothing to help Aboriginal people "stop the gap", in the words of a title that is more intent on being clever than intelligible.

It's a shame, because the exhibition itself is quite engaging. The idea was to bring together a number of contemporary artists from Canada, New Zealand and Australia who work with video and digital media. And not surprisingly, success is in inverse proportion to ideological tendentiousness. Preaching may appeal to your existing congregation, who will huddle together in self-righteousness, but it will merely annoy everyone else. And when preaching becomes moral preening it is even more distasteful.

The difference can be experienced in the first large room of the exhibition. At one end Dana Claxton has four huge screens arranged in a mirror composition, the outer pair showing traditional Indian rattles, the inner ones mostly devoted to more abstracted forms that seem to open and close with the pulse of the music, evoking life and sexuality, in spite of the cool blues and greens of the work. Periodically, the screens return to a meditative blankness.

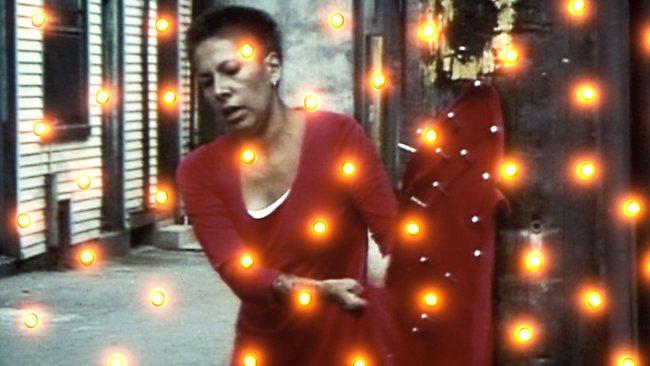

At the other end of the room is video by her fellow Canadian Rebecca Belmore, projected over a random assortment of low-voltage electric globes. The globes refer to a number of young prostitutes of indigenous background - the wall-text and catalogue are oddly coy about the occupation of the women - who disappeared and are presumed murdered (possibly by a serial killer) on the streets of Vancouver during the past decades. Belmore's video shows her scrubbing the footpath where they apparently worked, then lighting candles and calling out their names.

It sounds as if it should be cathartic and intense, but it ends up being rather self-conscious. Biting roses off their stalks descends into bathos. Partly the problem is a tone of resentful dourness, but partly it's just the fact of performance. Had someone simply carried out an expiatory ceremony for its own sake, it would have been quite moving. But turned into art, a product and a building-block in a career, it reminds one of what Christ said of the Pharisees who do their good deeds in public: they have had their reward.

As so often, this installation is noisy and intrusive as well, and makes it rather hard to appreciate a couple of more reflective works nearby. One of these is by Nova Paul, from New Zealand, and consists of seemingly casual footage of the artist's home, with figures walking around, setting the table and so on. These everyday scenes are transformed by a process of colour separation, with different parts of the image projected on different colour channels. The result is like an extreme form of chromatic misregistration, making figures float over others like ghosts to a meditative accompaniment of Maori guitar music.

Lisa Reihana, a contemporary Maori artist, has a set of eight small video monitors showing close-up views of the land on which her father once lived. There are flowing streams, bubbling pools of mud and stark rocks coloured with deposits of yellow sulfur and red cinnabar, the natural ore of mercury. The accompanying notes tell us that the land has been environmentally damaged, but this is difficult to convey with the close-up framing and the inorganic nature of a volcanic landscape.

Upstairs there is an impressive video installation by Scott Michelson, in which two long bands of riverbank move in opposite directions, one being the edge of an Indian reservation, the other part of European Canada. Also upstairs is a work commissioned from Warwick Thornton, better known as the director of Samson and Delilah, but unfortunately here starring in his own work, nailed to a floating, revolving white plastic cross in glorious 3D kitschorama.

Tuesday to Friday, 11am-5pm; weekends, 2pm-5pm. Free. Inquiries: (08) 8302 0870. Until April 21