Image conscious

VISITORS may experience a first moment of panic as they find themselves face to face with the impression of an inscription from several thousand years ago.

VISITORS to Casts and Copies may experience a first moment of panic as they find themselves face to face with the impression of an inscription from several thousand years ago in an early form of Semitic alphabetic writing.

But those who persevere will find it a rewarding exhibition, not only in its immediate content but in the historical and theoretical questions it raises.

What is copying? The reproduction of a text is relatively straightforward because it exists in a symbolic code that simply can be rewritten. A poem can be retyped or copied on the back of an envelope. A picture or sculpture, however, exists only in the unique material form in which it was made; we can make drawings of it (or take photographs), but these will always be partial views or simplifications. To make a proper copy, we have to remake the work in its original material form.

It is no easy matter to paint a good copy of a picture, but that raises questions that are beyond the scope of this exhibition. The copying of sculptural objects is difficult in different ways because they must be reproduced in three dimensions, although not necessarily in the same materials. The Romans made marble copies of Greek bronzes -- with the addition of braces and connecting pieces that were unnecessary in the originals -- because this was relatively easier and less costly; today, these are often the only records we have of masterpieces melted down by later barbarians.

The Renaissance, fascinated with antiquity, collected ancient sculptures and copied them. The studio of Donatello made enlarged sculptural reliefs of precious cameos to decorate the courtyard of Palazzo Medici. Later, in the 16th century, Primaticcio copied masterpieces from the papal collection in Rome for Francois I at Fontainebleau; some of the plaster casts he took were subsequently reproduced in bronze.

The invention of the pointing machine, in the 18th century, superseded the painstaking process of measuring with calipers, changing the working methods of sculptors from Canova to Rodin. It also made it much easier to copy existing statues and this, combined with nationalistic and educational ambitions in the 19th century, accelerated the formation of cast collections.

The greatest of these was, and still is, the Cast Court at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. Although the museum opened to the public in its present form in 1873, the collecting of copies had started more than 30 years earlier, largely through the efforts of Henry Cole. In the 1860s he promoted the idea of sharing copies of masterpieces internationally, and at the 1867 Paris exhibition an international convention was ratified to promote the "universal reproduction of works of art".

Other initiatives followed, such as the Musee des Monuments Francais in Paris, which opened in 1882 and was recently relaunched (after years of closure following a fire in 1995) as part of the Cite de l'architecture et du patrimoine (2007). In Australia, Redmond Barry, chief justice of Victoria, chancellor of the University of Melbourne and president of the trustees of the Melbourne Public Library -- the mother institution of the NGV -- collected a gallery of classical casts from 1859 to 1862, one of which, reproducing the recently rediscovered Venus de Milo, was included in the Irish exhibition at Canberra's National Museum.

Barry had hoped to create a Victorian museum of casts -- and it is noteworthy that in this he was absolutely in step with contemporary museology in London -- but there was no interest in the colony and the collection was dispersed, some of the works apparently later destroyed.

The Ian Potter exhibition includes explanatory panels relating a little of this history and explaining the value of copies not only for educational purposes but also as a kind of insurance against the possibility of loss and destruction: many works indeed have been preserved when the originals have been destroyed or damaged through environmental degradation.

One of the most interesting tales of original and copy in the exhibition is that of the Rampin Rider, a marble equestrian statue of a youth from the 6th century BC, destroyed during the Persian sack of Athens in 480BC. The head was found on the Acropolis in 1877 and given to the Louvre; parts of the body and horse had been dug up earlier, but the connection was not made until 1936. So today the Louvre has the original head with a cast of the rest of the statue, while the Acropolis Museum in Athens has the original body and a cast of the head. There are other interesting Greek objects in the show, but the most prominent and intriguing items are from the ancient Near East, cultures that are today much less familiar to us than Greece and even than the contemporary civilisation of Egypt. Most of these copies come from the British Museum, which holds the originals, and were collected for the University of Melbourne by John Bowman, who held the chair of Semitic studies from 1959 and was a pioneer of Australian scholarship in the field.

Perhaps the strangest of these objects is the cast of a model of a sheep or goat's liver from between 1900BC and 1600BC. These were used for divination purposes: after the animal was sacrificed, its liver would be studied by a specialist priest called a baru, who would interpret the marks and blemishes detected on its surface.

Many of the bigger objects are boundary markers or kudurru, made of a dark limestone and often recording grants of land or other legal acts. In one case, the Assyrian king Nebuchadnezzar rewards the master of his chariots, Ritti-Marduk, after a successful action against the Elamite enemy, with tax and levy exemptions for his whole town. The circumstances of the exemption, as well as the legal act itself, are recorded on two sides of a solid stone block while another side is covered in images of the gods and magical symbols designed to witness the deed and protect the stone.

Another black limestone tablet from Babylon celebrates the restoration of the temple and cult statue of the sun god Shamash (860BC-50BC), with an inscription recording the formerly dilapidated state of the sanctuary. The largest of the casts, however, is the obelisk of Shalmaneser III, set up in the Assyrian capital Nimrud during a time of war, and intended to remind the population of the power of their ruler, who is shown receiving tribute from his vassal states and dominions. The second row includes the first image of a Hebrew, the usurper king of northern Israel, Jehu, who was indulgent of idolatry and abandoned alliances with Phoenicia and Judah (the southern Hebrew kingdom after the split in the time of Solomon's sons) to submit to the Assyrians.

Particularly curious is the register of reliefs immediately below this one, which appears to record tribute from Egypt. Not only are camels brought, and an elephant, but also strange creatures with humanoid faces, which must be monkeys, one of which is sitting on the shoulders of his handler. Less plausible is a final set of creatures with human faces and lions' bodies, led on chains by attendants; presumably they are sphinxes, but it is disconcerting to see them described with the same matter-of-factness as the more familiar animals.

The main reason these pieces appear to have been collected by the university is for their written inscriptions, and there are many smaller and less spectacular objects similarly inscribed in cuneiform, which was developed about 5000 years ago and seems to be the earliest form of human writing. Cuneiform began as a pictographic system (which inspired Egyptian hieroglyphs) but evolved into a more abstract and summary combination of wedge-shaped marks originally impressed into clay with a sharpened reed.

The invention of writing revolutionised the way the human mind worked, allowing us to think in ways unavailable to preliterate peoples. But it was not until the invention of alphabetic writing a couple of millennia later that writing became widely and easily accessible; cuneiform, as one has little difficulty in understanding when looking at the minute rows of crabbed geometric marks on some of these tablets, always required specialist training to read and write, and this gave power to the priestly caste whose preserve early literacy remained.

Cuneiform was invented by the Sumerians and was adopted as the script for the Assyrian languages represented here. But it could, like later alphabetic systems, be used to transcribe other languages as well. From the 6th century BC there is a cuneiform cylinder that is in Persian, an Indo-European language: it records the conquest of Babylon by Cyrus the Great in 539BC. This was a happy occasion for the Hebrews, who were freed from the Babylonian captivity and allowed to return home, but the beginning of trouble for the Greeks.

The Persians tried and failed twice to invade Greece, the first time in 490BC under Darius and the second time in 480BC under Xerxes. Interestingly, a second cuneiform inscription, in large letters for public display, was made at the order of Xerxes and declares that everything he has done has been with the help of Ahuramazda, the Zoroastrian god, and praying that he will continue to benefit from his favour.

Two final reproductions are especially notable, both Roman imperial portraits from Britain. The first is of a bronze head of the emperor Claudius, the emperor who began the conquest of Britain, rather awkward and provincial in style, and dating from about 54AD-68AD. It was found in Suffolk in 1907 and once belonged to a life-size bronze statue that may have stood at Colchester and hypothetically could have been overthrown during the revolt of Boadicea in 61AD.

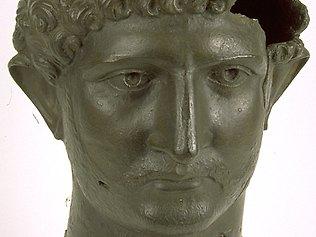

The other bust is a more rustic one still, in copper alloy, of the emperor Hadrian, recovered from the Thames. It too was hacked from its body at some later time, perhaps by Saxon barbarians. Presumably the main motivation in each case was to recover the valuable bronze.

But why cut off the heads? Perhaps it was a matter of superstition; perhaps the figure had to be symbolically "killed" to deprive it of the magical and protective power of the divine emperor.

Casts and Copies: Ancient and Classical Reproductions

Ian Potter Museum of Art, University of melbourne, until October 16.