German dilemmas

IT is fortuitous that Jacqueline Strecker's exhibition should open while The Enemy at Home is still showing at the Museum of Sydney.

IT is fortuitous that Jacqueline Strecker's outstanding exhibition devoted to German modernism should open at the Art Gallery of NSW while The Enemy at Home is still showing at the Museum of Sydney.

This exhibition, reviewed here three weeks ago, is devoted to the Germans interned in Australian prisoner of war camps as enemy aliens during World War I. What is compelling about the photographic images it comprises, mostly by one of the internees, is the picture they present of a sophisticated, disciplined people rebuilding a miniature society out of lives scrambled together and confined.

In more than one sense, and for all the injustice they suffered, these internees were the lucky ones, at least until their forced repatriation after the end of the conflict. For those at home not only suffered the unprecedented slaughter of trench warfare but, as the works in The Mad Square amply demonstrate, the near-collapse of civilised life under the stresses of war, military defeat, political collapse and revolution, terrifying epidemics of influenza and typhus, economic catastrophe and the struggle between competing versions of totalitarian tyranny.

Few realised, at its outbreak in 1914, how long or destructive the war would prove to be. Driven by nationalistic folly, plenty of people in France and Germany looked forward to the conflict with enthusiasm. Ernst Barlach's bronze sculpture of The Avenger (1914) is a monument of bellicose fervour, although the artist would soon come to change his mind. The horror of war itself is unforgettably captured in Otto Dix's etching of Storm Troopers Advancing under a Gas Attack (1924), their faces hidden by masks, and brandishing grenades.

The image is like a vision from a nightmare, yet Dix was so drawn to the violence and extremity of war that he repeatedly, and voluntarily, returned to the front. Afterwards, too, he continued to be grimly fascinated by the lasting evidence of the destruction in the thousands of grotesquely mutilated and disfigured men who continued to live on in the new Germany that followed the return of peace. How long, one wonders, could a man such as the one represented in the company of a diseased and pox-ridden prostitute (1923) actually live in this state? Perhaps as long as the descent of Germany into the madness of the next war? Certainly the Nazis disapproved of such images as Dix's War Cripples (1920), which they confiscated, displayed in the Degenerate Art exhibition of 1937 and later destroyed; allegedly the painting was disrespectful to war heroes, but in reality such work was simply demoralising in the eyes of a militaristic regime.

Not that what followed on the capitulation of the German army could properly be called peace. From the point in late 1918 that defeat became ineluctable, events raced ahead in a chaotic sequence that no one could really control. While early ceasefire negotiations were still under way, pressure mounted on the kaiser to abdicate, the army schemed to secure its future and civilian political parties struggled to avoid a collapse into the kind of Bolshevik revolution that had engulfed Russia the year before. A republic was proclaimed in November 1918, but agitation continued and by January 1919 the communist Spartacists revolted and were brutally suppressed, with the killing of Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht.

Meanwhile the devastating post-war flu pandemic, which had first broken out in the trenches, raged from 1918 to 1919, killing about 400,000 German civilians. In June 1919, the Treaty of Versailles was signed: the French had insisted on oppressive reparation payments from an already ruined German state, which ensured the persistence of anti-French resentment in Germany and exacerbated social and political conditions later exploited by Hitler. In the shorter term, these punitive reparations helped to precipitate the hyperinflation that destroyed what remained of the savings of ordinary Germans between 1921 and 1923.

Some of the most interesting works in the exhibition belong to these crucial years, from posters representing different sides of the revolutionary struggle to a woodblock in which Kaethe Kollwitz mourns the death of Liebknecht (1919-20). Not surprisingly, the dada movement, which had begun in neutral Zurich during the war, spread to Berlin in the immediate post-war period, and the exhibition includes works by Hannah Hoech and John Heartfield as well as those of Dix and George Grosz, who were associated with the movement. There are paradoxically beautiful collages made from tickets and other paper scraps by Kurt Schwitters, although he was rejected by the dadaists because of his connections to the expressionists.

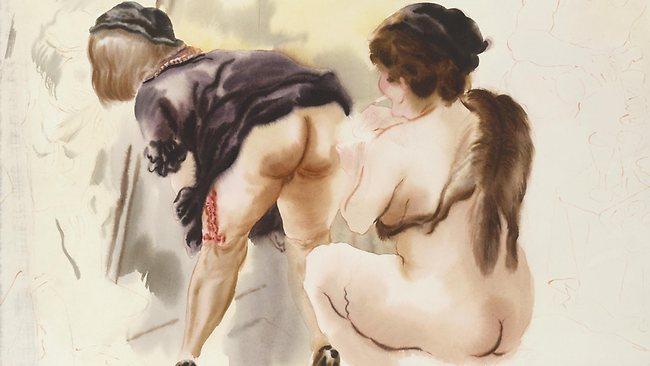

Most striking of all is the tone of despair and cynicism which seems to be the direct expression of the collapse of all social certainties: images of violence and suicide abound, some of them going back to the war years, such as Dix's Suicide (1916), in which the red-light district is the background for an hallucinatory vision of crime, misery and despair. The connection of sex and violence is particularly notable, from Heinrich Davringhausen's The Sex Murderer (1917), in which the killer lurks in the shadows beneath the bed of a naked prostitute, to Grosz's Murder in Ackerstrasse (1916-17), in which a fat and rather timid-looking man washes his hands in the basin of a cheap hotel room after beheading another prostitute with an axe. The theme returns with a gruesome ordinariness in Rudolf Schlichter's watercolour of one more killing in a sadly mean setting (1924).

Of course there was rebuilding after the war, during the 14 years of the Weimar Republic that lasted from 1918 to 1933; the currency was stabilised by 1923 and there were years of relative respite until the worldwide crisis of 1929. As unstable, corrupt, politically divided and ultimately doomed as the Weimar was, it coincided -- as Eric Hobsbawm writes in a brilliant piece reprinted in the catalogue -- with an extraordinary explosion of cultural, literary and scientific activity in Germany, partly stimulated by the sense of living on the edge of a precipice, in a world whose past had been abolished and whose future was unknown and perilous.

Berlin became the centre not only for German and Austrian writers and artists but for others from central Europe, the wreckage of the Austro-Hungarian empire and even from Soviet Russia. The members of the Bauhaus, based successively in Weimar, Dessau and Berlin, included Germans (Walter Gropius, Oskar Schlemmer), Swiss Germans (Paul Klee), Russians (Wassily Kandinsky), Dutchmen (Theo van Doesburg) and Hungarians (Laszlo Moholy-Nagy). It was this cosmopolitan, dynamic but dangerous city that became briefly the most vibrant centre of modern art and culture.

Among the memorable images in the exhibition are photographic records of the new industrial environment -- bleak urban skylines, views of factories or close-ups of machines: defining pictures of a colourless world of mechanised alienation. As though in counterpoint to these reminders of a harsh outside reality are the ideal, at times escapist compositions of contemporary painters: the geometric abstraction of El Lissitzky, the spiritual lyricism of Kandinsky and the whimsical forms of Klee.

The people who appear in photographs of the time are stylish but tense and self-conscious, such as the rather epicene young man and still more androgynous young woman, both by August Sander; she looks out at us -- or rather, past us, like a boy in a dress, holding an almost burnt-out cigarette in extraordinarily long fingers, elegant but brittle. She could be frigidly asexual but for her vulnerability; and we are left unsure whether we are looking at an aesthete of vice or a just an empty-headed narcissist who goes home to supper with her aged mother.

Sexual indulgence and the permissiveness of an underground culture were what attracted many to pre-Nazi Berlin, even if it was, as Rudolf Schlichter suggests in his pictures of a cabaret and of a sort of club for amateurs of assorted paraphilias, inevitably tawdry and even at times simply boring. This is the Berlin evoked by Christopher Isherwood in Mr Norris Changes Trains (1935) and Goodbye to Berlin (1939), which were eventually condensed into the musical (1966) and later (1972) film Cabaret.

Perhaps the most memorable single image in the exhibition is Christian Schad's self-portrait with a singularly disconcerting female model (1927); he sits, apparently perched uncomfortably on the edge of the bed, wearing an oddly creepy diaphanous green top, while she stares grimly away into the distance, her face marked with the scar or sfregio that was once common in Naples: a ritual scarification by which a woman was marked as a man's lover and that women are said to have worn with pride as proof that they were possessed and protected by a man.

Schad's picture, although particularly arresting, is surrounded by other paintings of the Neue sachlichkeit (new realism) movement, many of which are also of great interest, and particularly repay close attention to the way in which they are executed. Dix's portrait of Theodor Daeubler (1927) borrows from Albrecht Duerer, greatest and most canonic of German painters, even to the minute rendering of the hairs in the beard; but there is something at once theatrical and slightly unreal about the image of this poetic patriarch with the absent gaze.

Georg Schrimpf also alludes to the Renaissance in the fine portrait of his wife Hedwig (1922), but this image worked mostly in thin glazes remains ethereally disembodied; and on the other hand Grosz's Self-portrait with Hat (1928), while a vivid impression of the artist, is in reality only blocked out in areas of opaque paint, revealing and almost emphasising the artifice by which it is made, the gaps in the illusion. All of these portraits, vivid and sometimes brittle, thus reveal a certain instability or fragility in the very manner of their painting.

Such subtleties in the craft of painting itself -- such deliberate play with the range of effects and technique inherited from the tradition of oil painting for the purpose of dramatising the everyday, evoking inner life, and articulating states of uncertainty and anxiety -- parallel the complexities of music and literature at the time. But all this would soon be swept away by the rise of a movement that had no time for such introspective refinements.

The elections in the summer of 1932 made the Nazi party the largest in the Reichstag, without yet having a majority; by the beginning of 1933, however, Hitler was asked to form a minority government and his rise became irreversible. Among the strongest and most urgent images in the exhibition are the photomontages of Heartfield, satirising Goering as a butcher (1933) and Hitler, shown with a spine of gold coins (1932), and juxtaposing the pronouncements of Nazi propaganda with the misery of widespread poverty. And these images are from well before the outbreak of war; there was, in fact, much worse to come.

The Mad Square

Art Gallery of NSW, Sydney, until November 6