Adam Elliott: Inventive art of the human clay

The Oscar-winning Australian director behind Mary and Max returns with his first film in 15 years, Memoir of a Snail.

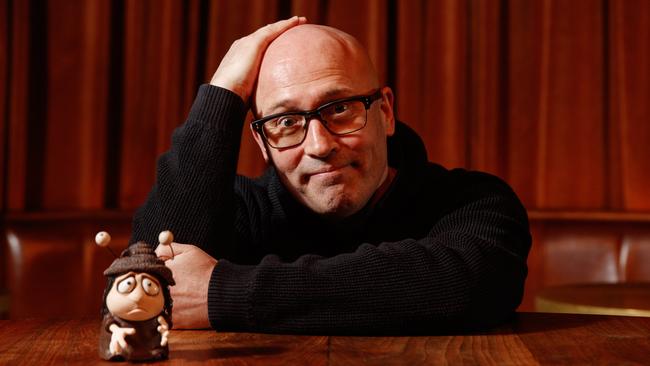

‘I am a very slow writer,” director Adam Elliot tells Life & Times on a drizzly morning in September when we meet to discuss his second feature, 15 years in the making, Memoir of a Snail.

We are at the Golden Age Cinema at Surry Hills, a holy place of gorgeous but admittedly uncomfortable green velvet seats in which Sydney cinephiles can watch the classics and art house oddities.

As we speak in the dimly lit bar area, the film’s star watches over us, looking as if she is on the verge of tears. It is Grace Pudel, a claymation model no bigger than a takeaway coffee, dressed in a hat that has been modelled to look like a snail shell. (Elliot: “Some people think it looks like an emoji poo.”) Her fine hair – made from individual wire strands – pokes out madly.

Elliot, 52, is an Oscar-winning animator (for the 2003 short Harvie Krumpet) who is best known for his 2009 feature Mary and Max – a superb stop-motion film that starred Toni Collette as Mary Dinkle, a lonely eight-year-old girl in Melbourne, who finds a penpal friend in Philip Seymour Hoffman’s Max Horovitz, a 44-year-old Jewish New Yorker with Asperger’s syndrome.

Memoir of a Snail, set in 1970s Melbourne, Perth, and Canberra, is a deeply personal, peculiar, sometimes outrageous and always moving exploration of grief, hoarding and transformation. It tells the story of Grace Pudel (voiced by Succession star Sarah Snook), a woman who copes with the death of her parents and separation from her twin brother Gilbert (Kodi Smit-McPhee) by collecting ornamental and real snails.

Elliot – who takes an earl grey tea, black, with a slice of lemon – explains that his stories always come from a place of frustration. “There’s something that has been bugging me,” he says.

In the case of Memoir of a Snail, it was the process of cleaning out his late father’s home – an already emotionally fraught situation made more stressful by the fact his father was a “mild hoarder”.

While Elliot and his siblings were sorting through their father’s junk so they could move their mother into the city from the country, the filmmaker had one persistent thought: “Why did Dad have all this stuff, half of which he’d never used?” From there, he started questioning why we collect things at all.

Elliot devoured books on the psychology of hoarding and “exploitative TV shows” such as the long-running reality series Hoarders, and learned that extreme hoarders typically have suffered from trauma.

“Usually it’s the loss of a child, twin or sibling,” he says. “They give sentimental value to everything they collect. That’s why they can’t bear to throw anything away.”

Later, flipping through his old journals, he came across notes he made based on a friend he was going to make a short film about who was born with a severe cleft palate. “As a kid she was bullied at school. Then as an adult she became this real extrovert, very flamboyant, the first person to take their clothes off at a party.”

He was fascinated by the idea of transformation, and the Grace character was born.

“I had my themes and ideas and I just started writing,” he says, admitting that he is prone to rewriting and “by the 34th draft, the plot started to come in”.

Elliot is obsessed with misfits, outsiders and underdogs. “All my characters have some perceived flaw or imperfection,” he says. He doesn’t set out to write characters like this but “by page three they have some affliction”.

What is it that he is trying to say through these characters? “To learn to embrace your imperfections as well as others’. You can fix some of your flaws, but a lot of them you have to live with.” He doesn’t want his audiences to sympathise with or pity his characters but to empathise. “I want them to see themselves in my character’s shoes. What would it be like to be born with a cleft palate and be bullied and teased? What would it be like to have Asperger’s and never been able to hold down a job?”

So, why snails? At first Elliot was drawn to ladybirds, having seen a documentary of a woman who hoarded anything to do with the bespeckled bugs. But then Greta Gerwig’s Oscar-winning comedy Lady Bird came out and thwarted that idea. “Also ladybirds are a bit cutesy, a bit twee,” he says. “I thought that Grace would collect something stranger.”

He considered ducks, pigs, dogs, the whole Noah’s ark, before deciding. “Snails are so alien and strange and it just felt right,” he says. “They are also a good metaphor for what’s happening to Grace. You touch a snail’s antenna and it retracts into the shell. That’s what Grace is doing her whole life, she’s retracting from the outside world.”

Elliot’s films aren’t documentaries but, he says, “there’s a degree of truth to every film”. He has coined the term clayography to describe his oeuvre. “It now has a Wikipedia, which I’m really excited about,” he says gleefully. “I can’t help but put myself in the films.”

Where Elliot’s father, Noel, was an acrobatic clown, in this film the father, Percy – voiced by Amelie star Dominique Pinon – is a French street performer.

Like most children, Elliot says he went through a period of loneliness, that ambient feeling of always being the odd one out. He is the first to say he was a “strange, peculiar, introverted” kid who often was bullied. “I was always drawing,” he says. “I was very creative but very shy at the same time.” He spent most of his young life wanting to fit in: “It’s funny how that changes.”

As a director, he has worked with the best in the business – Hoffman, Collette, Barry Humphries, to name a few. He initially had considered stars Cate Blanchett, Naomi Watts and Rebel Wilson to voice Grace, but ultimately went for Snook for her “beautiful quietness and vulnerability”. During the recording process, Snook bonded with the claymation figure of Grace in the sound booth. “She just talked to her,” Elliot says. “She’s so incredibly smart, she almost directed herself.”

This is Grace’s film, but “everyone’s favourite” is the character Pinky, voiced by Jacki Weaver. Pinky is an elderly former exotic dancer who had an airborne dalliance with country singer John Denver and once played table tennis with Fidel Castro, and is Grace’s only friend.

“Jacki turned it on and we had so much fun,” Elliot says. He originally wrote Pinky with a much saltier vocabulary, filled with choice four-letter words: “We recorded her swearing her head off.” In the end they toned it down to the milder dickhead. “We’d didn’t want to get an X rating,” Elliot says.

Elliot, who grew up in Melbourne, also got the city’s goth laureate, Nick Cave, on board “because I’m a frustrated amateur poet”, he says bashfully. Cave plays Pinky’s second husband, Bill, who meets his untimely end after being snaffled up by a crocodile. “He (Cave) asked what voice we wanted him to do. I said: ‘I just want you to be Nick Cave’, and he said: ‘How Nick Cave do you want me to be?’ So I said: ‘I want you to be the most Nick Cave you can possibly be.’

Eric Bana plays a disgraced magistrate who was disbarred for, ah, seeing to himself in court. “I had to direct Eric making masturbation noises … hilarious.”

The 15-year gap between features wasn’t entirely the fault of Elliot and his glacial writing process. It was also a matter of funding.

“What’s tedious is not the animating, it’s the financing,” Elliot says. “It’s a slow process. Even my accountant said: ‘Gee Adam, what you do is tedious.’ I said: ‘You’re an accountant!’ ”

Memoir of a Snail received major production investment from Screen Australia and was made for $7m. It’s chump change compared with other recent animated films such as Guillermo del Toro’s Pinocchio ($80m) and Inside Out 2 ($200m). “We have to do a lot with little,” Elliot says.

There are no special effects in the film. Elliot says movies are “drowning in CGI” and stop motion has that “slightly magical” thing that harks back to childhood, playing with dolls and inventing fantasy worlds.

Everything in Memoir of a Snail is made from something you can hold. The fire is yellow cellophane, the cigarette smoke is cotton wool. And the tears? At this, Elliot laughs: sex lube. “We went through litres of sex lube – for the rivers, oceans and the tears,” he says.

He refers to his team as “magicians”. “We’re tricking the audience with smoke and mirrors,” he says. “From the moment the film starts, they’ve got to suspend their disbelief and pretend these little blobs of clay have a heartbeat and a soul.” Many of the crew members with whom he works are neurodiverse: “ADHD, OCD, on the spectrum – and that’s an advantage.” Why? “They’re my best employees. They have the best work ethics. It’s hard to get them to go home, they’re obsessed by what they do. They like the isolation of animating in the dark. It’s a superpower.”

He feels lucky that the government has always supported his work. “They understand that my films are challenging. They’re not mainstream but they do reach a lot of people around the world.” Elliot wants to push boundaries. “If you don’t keep trying to give the audience something original, it all becomes formulaic, safe and predictable. That’s the best thing about being independent.” What is? “I can take risks.”

“Disney and Pixar have to be very careful with what they do,” he says. “I can have an orgy in my film, or a gay conversion camp. If we don’t talk about these things in art, then they never get spoken about.”

In previous interviews, Elliot has spoken about how his work has struggled to capture American audiences. “You never know how Americans are going to respond,” he says. He was concerned that a scene in Memoir of a Snail, where a church burns down, might ruffle a few Yank feathers. But it was a hit at the Telluride Film Festival in Colorado. “I met with Angelina Jolie and she loved it. It was incredibly validating.”

As our conversation wraps, a cinema employee meekly approaches Elliot to tell him Mary and Max is one of her favourite films, before scuttling away. It feels fitting, as if there’s a little bit of Grace inside us all.

Memoir of a Snail opens in cinemas on Thursday.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout