Disparate motifs woven into singularity

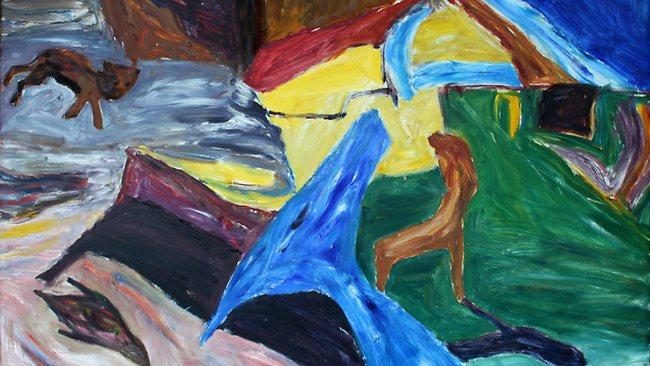

THINGS float away in Ken Whisson's paintings. They overlap and coincide in unexpected ways.

THINGS float away in Ken Whisson's paintings. They overlap and coincide in unexpected ways that consistently cast doubt on the reality of a rational and objective world, or suggest that the ebb and flow of associations and memories inside the mind is more important or in some sense more real, at least as far as art is concerned, than the apparent solidity and continuity of things outside the mind.

Forms are dislocated, and the human figure, in particular, is crushed, twisted and distorted, as though under overwhelming weight or pressure, while, paradoxically, seeming to hover in a depressurised vacancy. Throughout this extensive Museum of Contemporary Art retrospective that follows his long career as a painter, such images seem to evoke what the artist once called the "psychic deterioration" of our time.

These words were part of a declaration made almost 40 years ago, but they form the epigraph to the exhibition catalogue, and are repeated in a short video accompanying the show.

A more recent interview included in the book suggests Whisson's views have not changed greatly through the years: he is, for an artist who is in some ways elusive, a highly opinionated man, but, of course, an artist's opinions never match the meaning of his art in any straightforward way. Art doesn't deal with opinions or ideas but with something that is at once more general and deeper: with what could be considered at most the preconceptual, intuitive substrate of ideas. Thus Whisson's favourite themes, whether true or not, could be shared with any left-wing university student, while his painting embodies a view of the world that is individual and, at best, suggestive and memorable. It is a world of incoherence and interruption shaped by post-war anxieties and disillusionment and by the climate of thought and sensibility associated with such movements as existentialism, which dwelled on man's moral isolation and phenomenology, which emphasised the priority of subjective experience.

There is a table with a display of some of the painter's favourite books, including those by Samuel Beckett, who writes of the minimal survival of the human spirit in a social wasteland.

Some of the earliest works include a telling theme: crushed and crumpled human figures standing on a railway platform and juxtaposed with the loudspeakers that issue orders and instructions, and that are significantly solid and undistorted.

In later pictures, too, a variety of mechanical devices, particularly cars, which often look sinister, and other structures such as houses and fences suggest the boundaries and constraints that human beings produce like shells and within which they live much of their lives.

Whisson's compositions tend to be made up of distinct and even disparate parts, as though originating in a collage of motifs, and in some of them the parts remain disconnected. In the best of the pictures, however, unity is achieved through numerous devices, including the systems of horizontals and verticals that tie the individual sections and motifs together into the formal grid of the picture plane.

Colour, too, is an important means of ensuring compositional unity. Beginning with a grim and muddy darkness of his early expressionist work, Whisson develops in his maturity a lighter, clearer palette with subtler hues, which perhaps owes something to his long residence in Italy, where he has lived since 1977.

His home is in Perugia, the city of Perugino, who was the most important 15th-century exponent of the central Italian school and the master of Raphael.

In Whisson's most successful pictures, linear structure and chromatic affinity allow him to weave together motifs that should be disparate: thus the perspective of a tabletop extends into the vista of a landscape covered in factories and chimneys; or the interiors and exteriors of houses become part of a single and strangely plausible image.

Whisson's pictures make visible a certain sense of dislocation and complexity but, as so often, it is not the ones that overtly speak of angst that enter into the imagination and persist in the memory of the viewer.

It is, rather, those that remain more ambiguous, poised between disquiet in their motifs and harmony in their pictorial fabric. Indeed, for all the artist's expressly stated principles, the vision of his pictures is inseparable from their aesthetic.

And one of the most distinctive qualities in Whisson's aesthetic is the space he allows between the elements of his compositions. This gives the pictures a characteristic sparseness, an airy lightness that reminds the viewer that these are not records of things seen but the materialisation of something that exists only because it has been made by the craft of the painter.

Whisson has often dismissed technique and skill in painting but, like all artists, he has evolved the techniques he needs to serve his own particular ends.

Until November 25.

VISUAL ARTS

Ken Whisson: As If Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney.