Charmer of the Sydney school

MARGARET Olley's influence as an artist, model and benefactor will endure.

MARGARET Olley could be a formidable figure, ubiquitous with her walking frame in recent years.

Always an important personality at any Art Gallery of NSW event, yet perfectly accessible, she was quite willing to give the premier a talking-to about some issue that concerned her, but equally happy to speak to a young artist or art student who wanted to ask her advice.

Olley's work belonged to that post-war tendency sometimes dismissed as the Sydney charm school, akin to that of Jean Bellette (her teacher at East Sydney Tech, now the National Art School), Donald Friend and David Strachan, who were all close friends of hers. There is a certain decorative concern with form and colour, sometimes expressed in touches of neoclassicism, sometimes in an ornamental graphic style or a layered and textured use of colour.

In the catalogue of her AGNSW retrospective (1996-97), Barry Humphries brilliantly characterises the change of artistic fashion in the 1960s and 70s that dismissed all such artists as irredeemably slight: "When the tide turned in favour of sterile abstraction and slapdash expressionism", artists such as Olley were "excoriated by fashionable critics and uncollected by car salesmen and the wives of advertising executives and property developers".

But fashions come and go, and many artists come and go with them. Few have the sheer persistence to follow their instincts and indeed many find themselves with few resources of their own when the tide goes out. But for those, such as Olley, who have talent and endurance, time will be on their side: with every passing year, their position seems to grow more undeniable.

She was almost certainly the best-loved figure in the art world of Sydney, if not of Australia. In a milieu in which disparaging people behind their backs is almost a reflex, it is remarkable that she was almost never spoken of without affection.

Her generosity in personal relations is attested by the number of her friends and the many acquaintances who became very fond of her.

On a public level, she was equally generous in her gifts to Australian public galleries, which ranged from the work of Friend and Edgar Degas to sculpture and painting from India.

Olley painted mostly still lifes, but they were at the opposite extreme from the pared-down minimalism of Giorgio Morandi.

The most obvious difference between the two artists is in Olley's lavish celebration of colour, compared with Morandi's sparing use of it in predominantly tonal compositions.

Equally significant is the quasi-abstraction of Morandi's bottles and vases, a little parallel world of forms that come to exist on their own terms and evoke their own dramas. Olley's still-life items are also frequently recognisable from one picture to the next, but they always remain immersed in a life beyond the domain of the pictorial: they are bowls and jugs, vases and baskets and teacups.

Her still-life compositions imply a living domestic world around them, and it is not surprising that some of her most successful paintings are of interiors, views of rooms filled with tables and dressers, in turn covered in objects; the pictures that are more strictly speaking still lifes tend to focus on a single one of these tables and its population of household items.

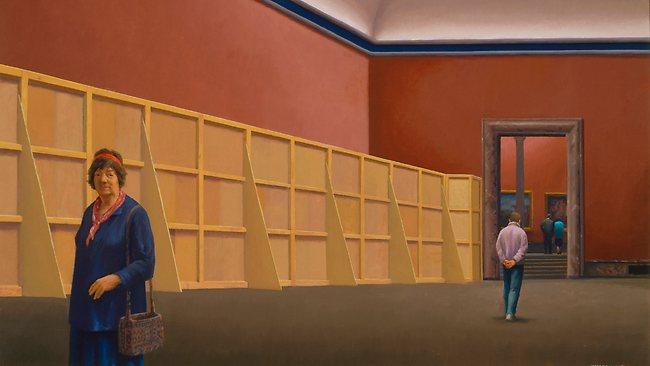

She was always drawn to the painting of interiors, and after the death of Strachan she painted some fine pictures in his house in Sydney's Paddington. Later, and most famously, she painted countless views of her own Paddington home, which her friend Jeffrey Smart described as "a beautiful magic cave of beguiling chaos". Every room was filled with collections of the sorts of things she liked to paint; in a sense, just as Monet ended up creating a garden to be the subject of his landscape painting, Olley created a house that was like a set for her own compositions of still lifes and interior spaces.

Olley was not only a painter but probably the most famous portrait sitter in Australian art. The first great portraits of her were painted by Russell Drysdale and William Dobell, both in 1948. In 1949, Dobell's won the Archibald Prize, only five years after he had been awarded the same prize for his painting of his friend and fellow-painter Joshua Smith, a win that had been challenged in a court case painful to artist and sitter; there was a new but less serious storm of controversy over the Olley picture.

Since then, Olley has been painted on several occasions by Archibald artists, including Nicholas Harding. This year, Ben Quilty again won the most talked-about prize in Australia for a portrait of Olley. Sixty-two years after the famous picture in the white duchess dress, the award inevitably seemed to mark the imminence of an ending.