Charles Darwin’s Australian adventure

Charles Darwin could not get over Australian marsupials, or Sydney property prices, when he dropped in on the colonies during his vogage around the world on the Beagle.

Charles Darwin looked forward to Sydney more than any other stop on his voyage around the world. After four years of travel, much of it in the wilds of South America, the young naturalist had built up Australia in his imagination as the “Empress of the South”, a place where he could catch up on letters from home and enjoy some much-needed English comforts.

Sydney did offer more civilisation than Darwin had seen in years. In 1836 it had a population of 20,000 Europeans, compared with a few thousand in New Zealand and a few hundred in Tahiti. Here the huts and shanties of the Bay of Islands were replaced by grand shops and mansions. Property prices were already soaring: Darwin was amazed that less than an acre of land had sold for £12,000, or more than £1m today.

But in the end the city left him disappointed. It brought out Darwin’s inner snob: he had been prepared to rough it in South America, but Sydney was supposed to be a reflection of Britain, and so he held it to higher standards. He recoiled from the “very low ebb of literature” in the bookshops and hated the idea of rubbing shoulders with reformed criminals who had become wealthy.

“Nothing but rather severe necessity should compel me to emigrate,” he concluded.

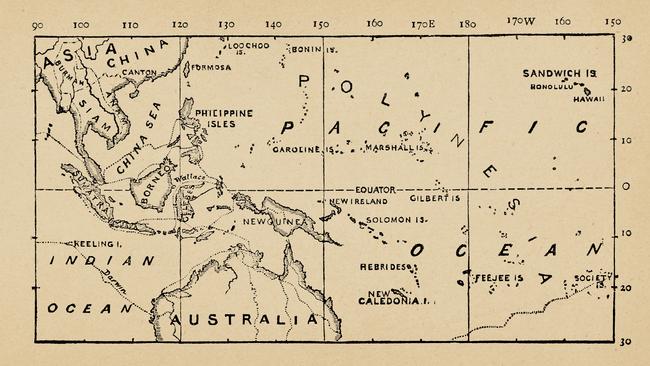

New Zealand received similar treatment in Darwin’s diary – “it is not a pleasant place” – as he hurried across the Pacific. The jaded traveller was deeply homesick, counting the miles until his survey ship, the Beagle, reached England. Not even the picturesque scenery of the Bay of Islands or the Blue Mountains could lift his spirits. But his work as the ship’s naturalist wasn’t finished, and his observations while in the Pacific would prove crucial to his later evolutionary theory.

In the Galapagos Islands, Tahiti, New Zealand and Australia, Darwin gathered reams of evidence for natural selection. He just didn’t know it yet.

There was the bizarre distribution of species in the Galapagos; and the dearth of mammals in New Zealand; and the strange character of Australia’s animals compared with those of other continents. These facts jarred with the wisdom of the day and left Darwin puzzled. Evolution hung over his shoulder as he tried to make sense of them, but broaching the subject on the Beagle was unthinkable, especially in the stuffy cabin where he dined every night with the ship’s captain, Robert FitzRoy.

In those days the Anglican Church was ingrained in every aspect of English life, including science. FitzRoy, a staunch Tory in the midst of a Christian awakening, was hardly the right sounding board for a budding heretic. The whole point of the Beagle voyage was religious, at least at the outset. FitzRoy wanted to plant a Christian mission in Tierra del Fuego, at the southernmost tip of South America. He thought it would have a civilising benefit on the Fuegians and offer a safe harbour for British shipping.

Darwin, too, was supportive of missionary work – when he joined the Beagle at age 22 his plan had been to become a priest. His favourite subject, natural history, was almost seen as a branch of the church, a way of knowing God and his works more intimately. Evolution was a dirty word, thrown around by lower-class radicals and dismissed by polite society. The establishment was so hostile towards evolutionary ideas that when Darwin came up with natural selection after the Beagle voyage, he hid it away in an envelope for 20 years, terrified of what his peers might think of him.

Eventually he stopped dithering – a malaria-struck Englishman in the Moluccas had come up with the same theory, forcing Darwin to act. He published his masterpiece, On the Origin of Species, and faced a firestorm from the church, the universities, and even FitzRoy, who regretted ever sailing with him.

In my new book, Darwin on the Beagle, I wanted to tell the stories of both men. Understanding Darwin’s opponents is key to understanding the man himself. The naturalist and the captain were on the same voyage around the world, yet they came away from it with very different conclusions and ended up on opposite sides of the great Victorian struggle between religious certainty and doubt.

There is no question that Darwin’s was the more resilient philosophy. He built his life on accepting hard truths, even when those truths were deeply uncomfortable. FitzRoy, on the other hand, was an idealist who held the world to impossible standards.

Obsessed with fairness and doing what was right, he moved from one disappointment to the next in later life. He loved science and even invented the modern weather forecast – but he refused to engage with his old shipmate’s theory because it contradicted his exalted view of man. The idea that he might be an animal with apes and molluscs in his lineage was too awful to contemplate. He took refuge in self-delusion, convinced that during the Beagle voyage he had gathered evidence for the Bible’s literal truth. FitzRoy died tragically by suicide, haunted by the part he had played in the making of the Origin.

Darwin’s rationalism could be bleak compared with the promises of Christianity; he was terrible at offering condolences to friends. But his commitment to clear-eyed reasoning gave birth to a theory that changed humanity’s understanding of itself and its place in the universe. It also helped him to present the idea to the public in a persuasive book.

One of the most striking things about the Origin is its honesty – the author presents a huge amount of data but freely admits what he does not know. The tone of the book is like that of a sympathetic neighbour who comes knocking with the aim of gently persuading the reader of an inconvenient truth. It says, “These are the facts I have gathered, what do you make of them?” In a world that prizes strong opinions and moral outrage, we would do well to remember that honesty, that refusal to be certain.

On one point at least, the Christians were right: natural selection was degrading to the dignity the human race had hitherto enjoyed. Darwin’s theory did seem to point the way to a depressing materialism. What was left of morality if man was an animal and the Bible was false?

The secularisation of the West was a process bigger than Darwin, and already under way when he released the Origin, though he had thrown an accelerant on the flames. Horrors did lie in wait for a world without absolute truth: centuries of jostling between political and social -isms, and the rise of ideologues such as the Nazis, who would co-opt Darwin’s theory for their own diabolical ends. Darwin didn’t wish for that fraught process and neither was he to blame for it. He certainly didn’t want to see his theory used to create racial hierarchies.

In recent years Christian scholars have attempted to link Darwin with Nazism. Others have tried to brand him as a racist – a strange charge to level at a man who hated slavery and genocide, and argued so strongly for the unity of man. Darwin may have viewed Britain as culturally superior to other nations, but he contended that the differences between human groups were superficial and gradual.

Were he alive to witness fresh controversies, Darwin would surely look on them with weary familiarity – mere echoes of the ad hominem attacks that followed him after he published the Origin. He kept a close tally of the abuse, and some of it wounded him deeply. But he kept returning to the same clear, unadorned question that had guided decades of his careful work: what was the best explanation for the diversity of life on Earth?

Darwin on the Beagle by Harrison Christian (Ultimo Press, $36.99) is out now.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout