Bye-bye, Bill

For a quarter of a century The Bill has had a passionate following, but now it's time to sign off

For a quarter of a century The Bill has had a passionate following, but now it's time to sign off

SIERRA Oscar One from Sierra Oscar . . . For years this was the way many couples in Australia communicated with each other on Saturday nights over dinner when long-running ITV police series The Bill was on. All uniformed officers in the long-running show had a radio call sign beginning "Sierra Oscar". This was followed by the number on their epaulette, except for the Inspector (who was Sierra Oscar One) and the Superintendent (Sierra Oscar Five-Two).

It sounds elaborate but The Bill provided a lot of fun, possibly even keeping some marriages together. We became intimately acquainted with the show's quaintly ornate lingo like no other, especially in the 1990s when the series was most popular.

Bill-speak and TB vernacular were everywhere, demystifying cockney rhyming slang and police shorthand such as panda (patrol car), spook squad (special branch), DI (detective inspector) and WPC (woman police constable).

"You're nicked," we shouted if the dinner was late, "Oi, you!" to attract our partner's attention if she neglected the wine glass, and "Just shut it!" when she wouldn't stop talking about how much she loved the handsome Jack Meadows, played by tough, taciturn Simon Rouse.

My wife had a crush on him for years. "He's got good hair, which most men his age don't," she'd say ominously.

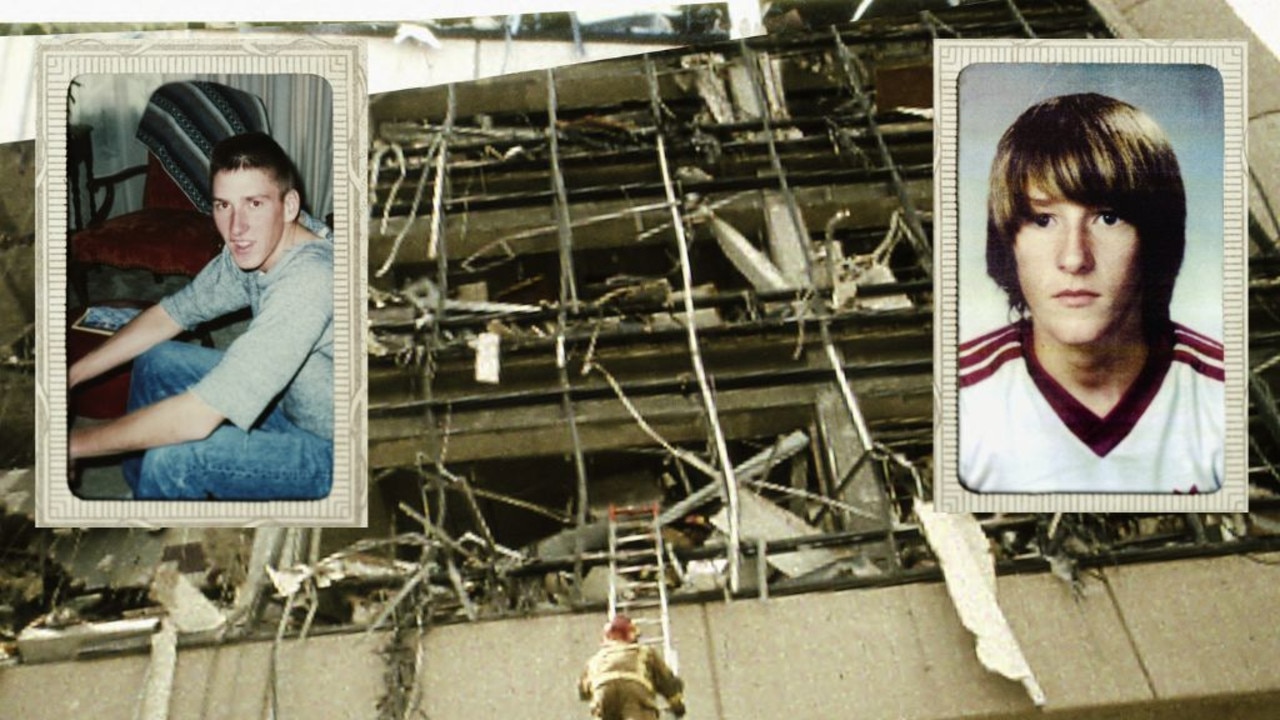

Meadows was certainly brisk, gruff and manly, calmly dodging the show's many explosions, race riots and fire bombings as it entered its final decade.

He also somehow survived the period when, unhappily for viewers, most of the characters' personal lives, including Jack's marriage, were unravelling.

We hated the attempts to "sex up" The Bill in recent years and the way new batches of producers turned it into a cop soapie in response, they said, to changing times and falling ratings.

The Bill, set in and around Sun Hill police station, in the fictional Canley Borough Operational Command Unit in East London, first appeared in August 1983.

It featured as a one-off play in the Storyboard series, under the title Woodentop, named after the street coppers' distinctive helmets; the show's closing credits for many years famously showed only the feet of two bobbies on the beat. It followed the first day at work of young PC Jim Carver (Mark Wingett), who was teamed up with the more experienced WPC June Ackland (Trudie Goodwin). The success of Woodentop led to a series being commissioned and The Bill was launched in 1984 as a drama serial.

Carver, a true plodder who battled alcoholism and was returned to uniform from his role as a detective, lasted 787 episodes. But the lovely, saintly Ackland, forever shuffling staff rosters, survived 1000 shows, though only after she became entangled in race riots, suffered stalkers and was left fighting for her life in 2004 after being hit by a police car.

If that weren't enough, she then had a fling with PC Gabriel Kent, played by former EastEnders star Todd Carty, who afterwards claimed to be her son. But whatever happened to our June, she never stopped smiling. On arrival at Customs in Sydney with Wingett on a promotional tour in 2005, she was waved on by officials. "You can go straight through, June," one said. "We know you're nice."

The series began as a subtle marriage of documentary and police procedural traditions, information combined with rather subdued entertainment; there was even a sense of the public service about the early shows. They presented us with genuine low-key working-class TV heroes, like that old-fashioned, thoroughly decent copper Sergeant Bob Cryer (Eric Richard), when there weren't many about, and regional accents were rarely heard on the box.

It was subject matter that, up until then, had been thought the province of British TV plays; but, with the principal characters established, The Bill had an advantage over conventional dramas because the story started on page one rather than page 10, as they tended to. For a long time it was one of the few top-rating shows in which the characters did not exist beyond their work environment. Certainly there was none of the sexual tension of NYPD Blue or the coy romance of the local Blue Heelers.

We thoroughly enjoyed this period of muggings and small-time robberies and admired the series for dealing with issues of racism and social deprivation. Every crime was a story and usually took an episode to laboriously solve. (As Clive James was fond of exclaiming, referring to the occasional pettiness of soft-crime episodes, "haven't they found that lost watch yet!")

The emphasis on uniformed coppers and their daily beat was so pronounced it used to provoke British football fans to chant "The Bill . . . it's just like watching The Bill" at increasingly heavily policed matches throughout the 80s and 90s.

Graham Cole, another favourite who played bluff and burly Police Constable Tony Stamp, described the acting style as "rep with cameras", pointing out that three units were always filming at any one time, "with little room for rehearsal and none for soapie prima-donna antics".

But the show never seemed comfortable in the past decade of popular culture's more nihilistic battle against TV's crooks, a period when democracy seemed to be only just holding its own against the gun-happy and deviant. Cops in so many shows crossed the moral line, reassured by their belief that conventional standards of society were no longer adequate guides to good conduct.

We'll miss Meadows, Cryer, Carver and Ackland, as well as later on Australian actor Daniel MacPherson, all leading lights among the more than 168 regular cast members who passed though Sun Hill's doors in the show's 27-year history. They were part of our lives for a long while, but it wasn't just the stars who caught our attention.

Almost from the beginning we also played "Hey, it's that guy" as the show seemingly provided work for every actor in the realm. It's an old industry joke that if you were ever to see three British actors at a table, two of them would have been in The Bill and the third most certainly had appeared in Taggart. On average, eight guest artists appeared in each episode, which adds up to about 19,200 actors during The Bill's history.

That doesn't take into account the featured extras, those same actors wandering around episode after episode in the background to scenes at Sun Hill. The production team called them all "Trev", as in "Truly Reliable Extra Veteran".

The show had a huge Australian fan base, addicts able to recite a rollcall of facts that would startle its screenwriters, and would go to extraordinary lengths to debate idiosyncratic details with fellow fans.

They weren't all homesick Poms, either, or off-duty cops scrutinising the procedures of the bobbies on the beat at Sun Hill; the fans here were as diverse as the show's large cast. They had their own periodical, Serious Police Work, a quarterly newsletter for Australian fans that acted as an unofficial information exchange for Billies, as they called themselves.

With its vast ensemble cast, The Bill had no real superstars, except maybe the city of London itself. But membership of this newsletter club fell away after the departure from the series of Nick Ellison, who played the toughest thief-taker of them all, Detective Inspector Frank Burnside.

Ellison left in 1993 and Billies are still divided as to whether Burnside was a bent copper, though even his most loyal fans admit that he was slightly on the dodgy side. When he went it was the beginning of the end for The Bill.

As for so many, it has been a while since I watched and I feel oddly guilty now that it's gone, especially as this last grimly realistic double episode, which concludes tonight, is such a good one.

It's a tough The Wire-like tale of disaffected youths and the terrible happenings on an inner-city housing estate: rapes, murders and drug dealing. It concludes with a press conference where Jack Meadows delivers an impromptu speech on the nature of respect and how, somewhere along the way, someone changed the meaning of the word.

It may just be, as some English critics have suggested, old Jack giving the two-fingered salute to the men in suits who pulled the plug on his show.

OBSERVATIONAL documentaries are not always the most illuminating TV shows. They're usually too reverential, too worthy, often rather pretentious and seldom get under the skin of their subjects. We want cameras to poke their snouts into all those areas forbidden access to the public, for an unauthorised biography, not a sanctioned marketing exercise.

Well, Theatreland, a new eight-part series, illuminates many dark corners of how professional theatre is brought to the public. It's especially fascinating for anyone who has never been backstage during a performance and witnessed actors, saturated by their roles, transform as they move from behind the side curtains on to the stage, reborn as someone else. Director Chris Terrill, widely credited as the "father of the docu-soap", does fossick around and ask sometimes difficult questions. He's famous in documentary circles for his so-called "lone wolf" approach, developed in films such as Commando: On the Front Line, his powerful account of Royal Marines fighting in Afghanistan. Terrill directs, handles the camera and asks the questions, his voice and physical presence part of his aesthetic.

Theatreland is a trip behind the scenes of London's historic Theatre Royal Haymarket, six fly-on-the-wall months covering every angle of the arrival of new artistic director Sean Mathias and the lead-up to his production of Samuel Beckett's Waiting for Godot. It's the same show that recently toured Australia, but here it stars the original London cast of Ian McKellen, Patrick Stewart, Simon Callow and Ronald Pickup. In this week's second episode the cast faces a first-night audience of celebrities and, hidden in the shadows, the dastardly London critics.

The lovely old theatre dates back to 1790, making it the third oldest London playhouse, one of the first to gain a royal patent to play "legitimate" drama, as opposed to opera or plays with music. The Haymarket has been the site of a couple of significant theatrical innovations, too.

It was the venue for the first scheduled matinee performance in 1873, establishing a custom soon followed in theatres everywhere. Six years later, its auditorium was reconstructed and the stage enclosed, in the first use of the picture frame proscenium.

Few theatres have seen representations of so many periods and places, or such extravagant displays of collaborations or misalliances. Terrill finds plenty of crises at which to point his camera, most emanating from the inexorable demands for refurbishment and maintenance the old venue demands of its staff.

It's great watching old stagers Stewart and McKellen exalting in the camaraderie of backstage life and its oddly tender superstitions. But it's unknowns Tony Brunt and James Whitwell who catch the eye, the master carpenter and his deputy coping with collapsed ceilings and leaky toilets with humour as grim and sardonic as Beckett's.

The Bill, Saturday, 8.30pm, ABC1. (Next Saturday ABC1 airs The Bill Farewell Special at 8.30pm, which includes interviews with the show's stars through the years and actors such as Keira Knightley and James McAvoy who became famous after appearing in it.)

Theatreland, Sunday, 8.30pm, ABC2.