New Netflix documentary Oklahoma City bombing reveals unseen McVeigh tapes

When Timothy McVeigh was executed, relatives of his 196 victims watched the execution on closed circuit television. But while a nation wished fervently for justice, the result rang a little hollow.

“The fascination with murder and illegality is a perennial one, because the shock of the deed creates a schism between order and chaos,” Sarah Weinman said in an introductory note to her fine anthology, Unspeakable Acts, True Tales of Crime, Murder, Deceit, and Obsession. “We wish for justice, but even when we get it, the result rings somewhat hollow.”

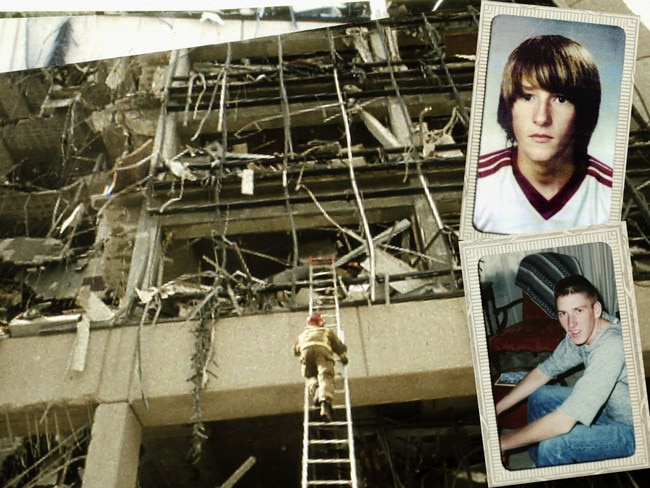

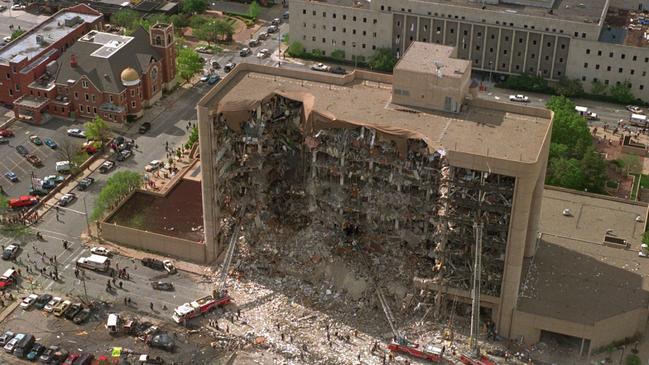

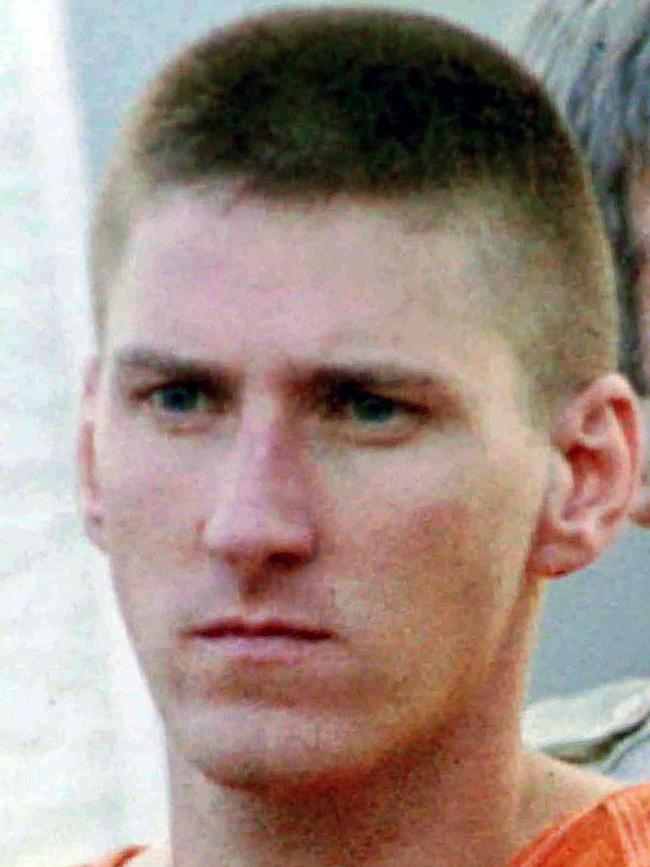

This is the way many felt about the outcome of the heinous act of destruction that occurred on April 19, 1995, when a loner called Timothy McVeigh, a disaffected right-wing extremist, detonated a bomb, planted in a rented Ryder truck, outside the Alfred P Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City, killing 168 people, including 19 children. More than 300 adjacent buildings were destroyed or damaged and shattered glass covered a ten-block radius.

The bomb was made out of a cocktail of agricultural fertiliser, diesel fuel and other chemicals. A third of the building was reduced to rubble with many floors flattened like pancakes. McVeigh targeted the Murrah building largely because it was full of US government workers; 14 federal agencies had offices there, and 98 of the victims worked for the federal government.

McVeigh was executed in 2001, three months before 9/11, and relatives of his victims watched the execution on closed circuit television. But while a nation wished fervently for justice, the result rang a little hollow, the hangover of trauma too great to be completely assuaged. As Weinman suggests so often when such terrible things happen, “We crave a narrative that restores righteousness but are left with scraps of barely connected meaning.”

There was some dismay after his execution, a sense that an opportunity had been wasted. As the writer Andrew Gumbel suggested, “Part of the reason for that lost opportunity is the US government’s failure at trial to tell the full story of who McVeigh was, the subculture he moved in, and the deep ideological wellsprings that led to his act of folly.”

He called it “America’s forgotten tragedy”, overshadowed by the events of 9/11.

The story of the single deadliest act of homegrown terrorism in America is the subject of the latest Netflix true crime documentary, Oklahoma City Bombing: American Terror, from executive producer and director Greg Tillman, alongside producer Tiller Russell, who gave us Waco: American Apocalypse, Night Stalker: The Hunt for a Serial Killer and American Manhunt: The Boston Marathon Bombings.

The hour and a half film comes as the bombing finds itself being discussed in the cultural ether, the documentary released to commemorate its 30th anniversary, with the right-wing extremism that motivated McVeigh on the rise in America. The events portrayed are not just a tragic contemplation on the past, no well-meant commemoration, but a cautionary tale about the future. As Russell says: “When history is at its most compelling, it’s not just a retrospective fact-finding mission but rather an enterprise that holds up a mirror to who we are today. As William Faulkner brilliantly put it, ‘The past is never dead. It’s not even past’.”

Russell is an old hand at the now relatively conventional Netflix true crime genre, and American Terror is not particularly ambitious aesthetically but sturdy and workmanlike in its dramaturgy. It’s a relatively straightforward retelling of the tragedy, initially walking us through the details of the bombings in an hour-by-hour way – there’s even a graphic ticking away the seconds – as Tillman and his editors contextualise the events into a coherent narrative.

Their idea is to really replicate the confusion and chaos as they were first experienced by both those involved – the first responders, the doctors and nurses who quickly appeared on the scene, and the law enforcement officers desperate to solve the case – and the public watching on their TV screens. It’s a disarmingly clever approach, detailing moment by moment the destruction and the following disorder, and then the seemingly miraculous serendipity that led to the major break in the case.

And while the series is relatively conventional in its methodology – talking heads intercut with some abstracted re-enactments, archival news footage, commentary from reporters, and some sequences largely composed from the video material provided from onlookers – it’s still a powerful piece of filmmaking.

Tillman was able to also draw upon the so-called “McVeigh Tapes”, a collection of audio recordings and writings from the bomber in prison, his voice dispassionate and impersonal, with no signs of remorse. But Tillman chooses not to glorify McVeigh in any way, his film an homage to those who not only suffered but participated in the rescues; during a postscript, he dedicates the film to the victims and survivors.

Tillman works from what is now the accepted template for Netflix documentaries, the filmmakers like cold case detectives re-examining the evidence, recreating timelines and recounting the shifts in perspective of the original investigation. The major change came after media reports and self-proclaimed “terrorism experts” linked Muslims, Arabs and “Middle Eastern-looking men” to the blast.

Using the not unfamiliar device of that digital graphic ominously ticking down, Tillman takes us through the events as they occurred, in exactly the same way they were experienced by the public, using the startled TV press reports as a kind of de facto narrator.

He begins with some touching home video style of several offices inside the Murrah building before the explosion. A camera wobbles from room to room introducing workers at their desks pleased to be included in this celebration of their community. “In here is Pammie,” a voice over says, “and she’s just a sweetheart.”

Then we are immersed in the chaos and destruction, the arrival within minutes of fire, police, and medical personnel on site, and the creation of a mass casualty triage as victims are pulled out. Along with civilians digging for bodies, the police are securing the crime scene and the FBI is starting its investigation. “In spite of the horror that they’re all experiencing,” Tillman says in an interview with USA Today, “so many people in that moment found a heroic piece of themselves that they may never have known about until something like this happened in their life.”

As the time ticks away, we are privy to the seemingly piece of miraculous fortune that leads to a break in the case when McVeigh is apprehended approximately 77 minutes after the bombing when Charles Hanger, an Oklahoma State Trooper, notices his yellow Mercury Marquis lacks a licence plate on Interstate 35 near Perry, Oklahoma. He pulls McVeigh over and subsequently arrests him for unlawfully carrying a handgun.

Tillman threads through the story the accounts of three people in particular. Dr Carl Spengler performed onsite triage after running to the site from a breakfast meeting nearby. Renee Moore worked near the building and her six-month-old son Antonio Cooper Jr was among those killed. She recalls nights where she would drive to McVeigh’s prison and “just sit out there in the dark, wondering how I could get in so I could hurt him”.

And Amy Downs, an employee of the building’s Federal Employees Credit Union, regained consciousness still in her office chair but upside down beneath a mountain of debris. Rescuers located Downs but had to flee before they could free her from the rubble after authorities thought they had found a second bomb. “They were leaving me buried alive,” she says. “And I’d start thinking about my life and relationships and doing something with your life to help others, and I’d never been a mom.”

Stillman winds in the way McVeigh was motivated by the events of the Waco siege in 1993, where the FBI engaged in a 51-day standoff with the Branch Davidians, a small religious group suspected of owning illegal weapons. But there is little space in his propulsive retelling of the bombing for any real discussion of the way right-wing extremism influenced him. Or how McVeigh’s principles and tactics have flourished in the decades since his death.

It’s hardly difficult, as the writer and lawyer Jeffrey Toobin has written, to find ominous parallels between McVeigh’s political motivations and the values and views of the January 6 insurrectionists.

Oklahoma City Bombing: American Terror, streaming on Netflix.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout