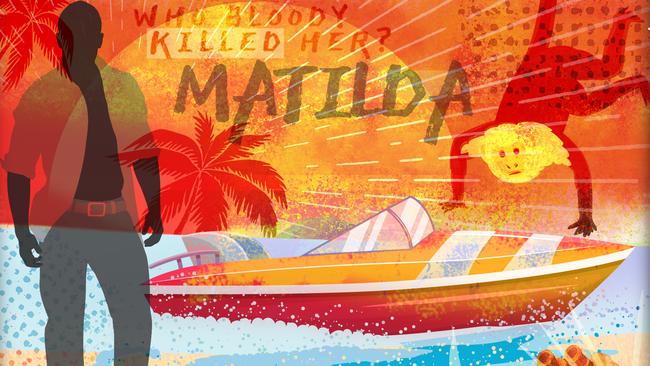

Oh Matilda: Who Bloody Killed Her? Chapter 9

Hang on, someone else has been murdered. Not on the island. Back in the memory of one of our characters. The Australian’s chief cricket writer Peter Lalor takes up the story.

This is ‘summer reading’ like nothing you’ve read before: a diverse field of writers collaborating on a novel that will captivate you through summer.

Each author had just three days to write their chapter, with complete freedom over story and style; it’s fast, fun and very funny.

Tune in over the summer to see how the story unfolds.

Today, Peter Lalor continues the story with Chapter 11.

By Peter Lalor

It was De Kock.

He was not in the room but he was not far away.

This moment needed a drone shot that lifted above the tropical stylings of the Pandanus Lounge before swooping across the lawn and over the small rise behind the resort compound.

Zooming in along a long, narrow beach it would have found the lone island deputy manager wandering deep in thought.

He seemed larger. Harder. His shoulders surprisingly broad. If you looked closely the suggestion of darker roots in the hair and a look hitherto unrecognisable in the eye.

De Kock had unbuttoned his khaki shirt and exposed himself in a way he rarely did. The stiffening island breeze blew it open and it flapped behind him. He ran his fingers across a scar that emerged from below his belt line and finished below his throat.

He’d hidden the scar as well as he’d hidden his real story, but he needed to clear his mind.

It was lazy to drop his guard but he had little respect for these Australians and knew they’d be huddled inside.

A weak nation. Soft people who strapped themselves in with their seat belts, obeyed all rules and at the first hint of a crisis sobbed like children and demanded mummy make it better.

More regulations, more protections. They fenced themselves from danger by building protective barriers on mountain walks.

An island girt by sea? Bah, they were an island girt by cotton wool. Good at bullying the weak, they’d have become a continent incontinent at the thought of the problems which beset his troubled home.

They still had a Queen. You didn’t need to be Freud to work out what was going on there.

A song from the South African radio of his youth played gently in his head.

Sugar man met a false friend

On a lonely dusty road

Lost my heart when I found it

It had turned to dead black coal

When he’d first arrived at this child-minding centre passing itself off as a country he thought he detected an emerging rank with whom he could identify. There was a figure he’d admired. Something about his cold eyes and contempt had suggested kinship, but De Kock soon realized that he and those who rode with him were as shallow as the rest. Circus performers seeking attention.

Look at me, look at me.

He had and he knew. They were actors performing rehearsed lines for the cameras. If push came to shove they sobbed and shivered and demanded mummy make it better just like all those they blew raspberries at for a living.

De Kock knew he shouldn’t indulge, but he allowed himself some reflection on the turns of fate that had brought him to this place here where he’d been forced to cover his hard edges and adopt the persona of a boy scout leader.

The twitcher thing was something he’d stumbled on while flicking through the pages of a book by an eloquently indulgent English cricket writer when scrambling to leave Africa on a special flight.

Sugar man, won’t you hurry

‘Cos I’m tired of these scenes

The plane crashed just before his had taken off.

A storm had passed through Jo’burg delaying his departure, the same one that had buffeted the lumbering cargo flight whose most precious contents had once been the captain of the national cricket team and hero of the Afrikaner people. He was supposed to be in the air by then.

The storm had provided additional cover but was not the cause of the accident, not that any cover was needed, because the Civil Aviation Authority report which would be released years from now had been written a month before.

He loved cricket but cared little for the fate of this weak one. He watched the game, but mostly he liked to read about it. One local writer in this port became his favourite; Gareth Cadbury had a turn of phrase that whispered to a hidden part of De Kock. There was something almost erotic in his wry, intellectual observations, although Cadbury let his soft-centred politics show a little too often.

De Kock had never questioned his role before. Slip through the night and slice a throat or two here or there. More than once he’d dropped into another troubled country to the north, completed his job and been back beneath the sheets before the sleeping pills he’d ground into his wife’s drink began to wear off.

The bottles of Stellenbosch wine she swigged every afternoon with the entitled princesses of the adjoining compounds had covered the concussive effects of the pills, possibly even smoothed the hangovers.

When she got that look in her eye he knew how to handle it. Another pill, another night unmolested by this drunk creature he chose as cover.

He remembered how the gibbons shrieked at night, mocking barking hounds from their refuge in the trees.

He’d killed men black and white. Large and small. Women were rarely the target, but occasional collateral damage. He’d learned all manner of tricks to hold any hint of guilt at bay. Mostly he’d imagine the long manicured fingers of his ‘wife’ tapping the perspiring glass of white wine.

Killing the cricketer, however, had set off a chain of events he could not control. The flight to the United States that night had gone to plan, but when he arrived in Texas all communication had stopped.

It was a sign and he knew what it meant. Somewhere something had gone wrong and his time was nearly done.

He’d changed his hair so many times that, like the man in the song, he’d forgotten what he looked like. He’d been American, South American, hell, once he’d even passed himself off as a Parsi, but here it was easier to be what he was.

It took a bit to rattle De Kock but the events on the island had got under his guard. Maybe he’d been among these Australians too long.

The night before, as these children made their way back to their accommodation, clutching their keys, he’d wandered to the jetty to curse the stars that led him here to this place.

From what was he running? He wasn’t sure, probably bookies, inevitably politicians in their grasp. Himself? He wasn’t even sure who he was anymore.

That last job was 18 years ago and while he’d picked up a similar line of work in Australia things had got messy on an assignment for an Indian coal mining company and so he found himself in this place, in this disguise, in this shit situation which would almost certainly attract more attention than he’d like, but not nearly enough for the pathetic members of the attention seeking industry that had descended on the island a few days before.

He’d noted that it had been a steady hand that had done for Matilda. The poisoning of Dario was a little English murder mystery, but effective. The Russians seemed attracted to the theatre of it. The Israelis thought it beneath them.

He’d used poison before but preferred the personal touch. If you want to do a job, do it yourself.

The wind grew stronger on the beach and De Kock shuddered at the horror of what he’d witnessed.

Not the gaping throat of Matilda or the foul gaseous stench Dario’s corpse emitted as his intestines bubbled like a test tube, but rather the scenes glimpsed the night before.

Driven by a need to understand just what the hell was going on he’d set out to do some surveillance once everyone had locked their doors.

It was a glimpse into a world he’d never imagined, but should have expected.

Through one window he’d seen that fat actor in all his naked ignominy. Attempts to raise the flag had failed despite much frantic flapping. The woman, whom De Kock had considered a little separate to the crowd, was propped up on pillows, her pitiless eyes surveying a scene she was all too familiar with.

De Kock watched as McCreddan climbed astride the long limbed Churchill and vainly tried again.

She looked at him in the way a person who has ordered the steak looks at a plate of tofu delivered by mistake.

It was then he heard the angry voice of a woman in another of the apartments. Leaving one observation point for another he watched as another weeping man child was belittled. Mother was incensed and berating Bradley.

De Kock was impressed by the way she broke him down, then watched with interest as she offered him comfort in his arms. It was a tactic he knew well, but one usually played out in cold rooms with harsh lights, not softly lit bungalows.

Mother now stroked the sobbing Bradley who clung to her like a newborn.

Just then thunder clapped in the distance and De Kock snapped backed to the present.

He looked up from the beach to the horizon where a small but fast moving craft made its way toward the island.

A massive storm front snapping at its heels.

For app readers, swipe to the Summer Novel section to find all chapters or click to read Chapter 1, Chapter 2,Chapter 3,Chapter 4 or Chapter 5.

Peter Lalor is a journalist, author and The Australian’s chief cricket writer. He co-hosts the Cricket, Et Cetera podcast for this newspaper with his friend and fellow journalist Gideon Haigh.

Twitter: @plalor

cricketetc.com.au