We should treasure the hard, bright intensity of youthful genius

Bob Dylan and Bill Gates showed the world can be changed by daring twenty-somethings — but is that happening now?

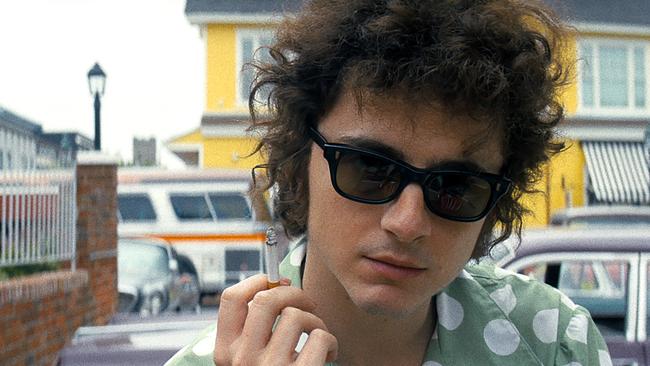

In A Complete Unknown, Timothee Chalamet nails the Dylan voice, the Dylan walk, the Dylan snigger, the Dylan slouch. One complaint: the sharpness of his cheekbones. The visage that peeks out from behind a sheepskin collar on the cover of the real Bob Dylan’s debut album is so baby-faced it might belong to a King’s College choirboy gone native in the backwoods of Minnesota.

Dylan – the fact staggers any reasonable person – was 21 when he wrote A Hard Rain’s a-Gonna Fall, that louring masterpiece of prophecy and allusion. His sequence of culture-transforming, for-the-ages albums – The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, Bringing it All Back Home, Highway 61 Revisited, Blonde on Blonde – was completed by his mid-20s.

To listen to those records is to be reminded that there is a hard, bright intensity to the flame of youthful genius that doesn’t burn much past 30. A lot of the greatest lyric poetry in English is the work of men and women (I might almost have written boys and girls) scarcely out of their teens. Coleridge was 25 when he wrote Kubla Khan; Keats composed his Ode to a Nightingale at 24.

Psychologists tell us that “fluid intelligence” – the power of speed, abstraction and logic – peaks at 20. “Fluid intelligence” will strike most Dylan fans as an apt description of the flashing currents, spiralling eddies and surreal gushes of association that characterise his best songs.

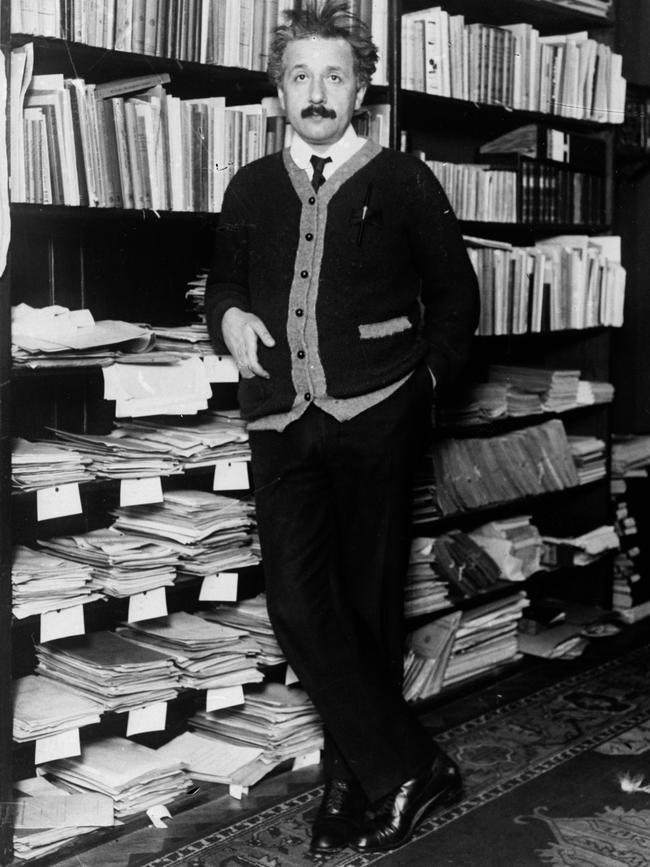

“Fluid intelligence” is also the hydraulic force that drives many of the great breakthroughs in physics and mathematics. Most of the pre-eminent geniuses of 20th-century physics started young: Werner Heisenberg, Niels Bohr and Paul Dirac were 23, 28 and 26 respectively when they made their world-historical achievements in the discipline. “A person who has not made his great contribution to science before the age of 30 will never do so,” said Einstein in a phrase that haunts tardy PhD students. He published his own special theory of relativity at 26.

The Fields Medal for mathematics is awarded only to those who are 40 or younger.

This is not to suggest that poetry, algebra and song die in middle age (look at the late careers of Thomas Hardy or Leonard Cohen). Nor is it to deny that other, equally important powers flourish later in life. “Crystallised intelligence” – the accumulation of knowledge, facts and skills – grows throughout life. Novelists whose work requires wisdom and stamina tend to peak later than poets. Great visual artists often make their most profound statements when deep in old age: Michelangelo, Titian, Rembrandt, Monet, Goya. But youthful genius has a special, anarchic power that our society is not currently good at harnessing. If the 1960s worshipped youth, the 2020s treats it with smothering condescension.

The first decade of adulthood should be one of electric inspiration but it has bafflingly been recast as one of infantilising apprenticeship: internships, postgraduate degrees, financial dependence.

A 21st-century film studio would be more likely to offer the 25-year-old Orson Welles an unpaid internship than the budget to make Citizen Kane. The modern Niels Bohr might be stuck wasting his time applying for insecure short-term “early career” jobs at universities. And the modern Mr and Mrs Zimmerman would probably be reluctant to allow their penniless teenage son to motorcycle off to Greenwich Village in search of his fortune. Perhaps the modern Dylan, raised indoors on an iPhone, would not want to go.

Watching A Complete Unknown, it struck me that if (as is often remarked) our culture seems tired and repetitive, perhaps it is because it fails to give a proper outlet to the energies of the young. Their stupidity, bravery and ambition can be irritating, especially to our cautious, credential-obsessed age, but it’s vital to progress.

Even ignorance can be a virtue when it allows you to blunder past the accumulated libraries of accepted wisdom to tackle the fundamental questions for yourself. And only a person possessed of the arrogance of youth could have ignored the protests of the Newport Folk Festival organising committee and blasted the unwilling audience with an electric guitar. An older man might have been more sensitive to Pete Seeger’s painstakingly constructed project.

And an older man probably couldn’t have made Highway 61 Revisited. Sometimes, you need to be a little cruel and a little stupid to go forward.

Often what the young contribute is energy. Talking to The Times at the weekend, Bill Gates recalled the “insane” schedule of his 20s. Sheer monomania is an important part of what many young start-up founders offer their businesses. As Gates says, such commitment becomes less viable as you grow older, acquire a family and begin to reflect that you do not want to lie on your deathbed looking back on a life of uninterrupted coding.

Not everyone has Gates-level energy, but it is strange that our society channels so much youthful drive and passion towards trivial tasks such as fetching coffee and writing masters theses.

Sociologists sometimes speak of “demographic metabolism” – the process by which societies process generational change. Our demographic metabolism is sluggish at present. We are richer than ever in the wisdom and skill of the old; artists and rock stars reliably have careers into their 80s. But if the 2020s can’t match the excitement and innovation of the 1960s it is perhaps because we are bad at taking advantage of the energy of the very young. A more tolerant attitude towards the baby-faced may be part of the answer.

THE TIMES

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout