For better or verse: when Bard of the Bush took on city-based modernist

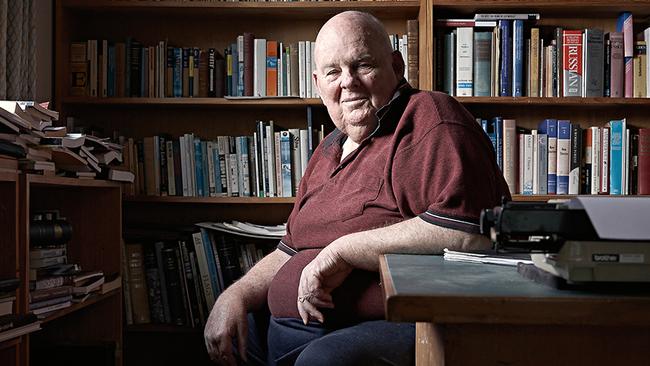

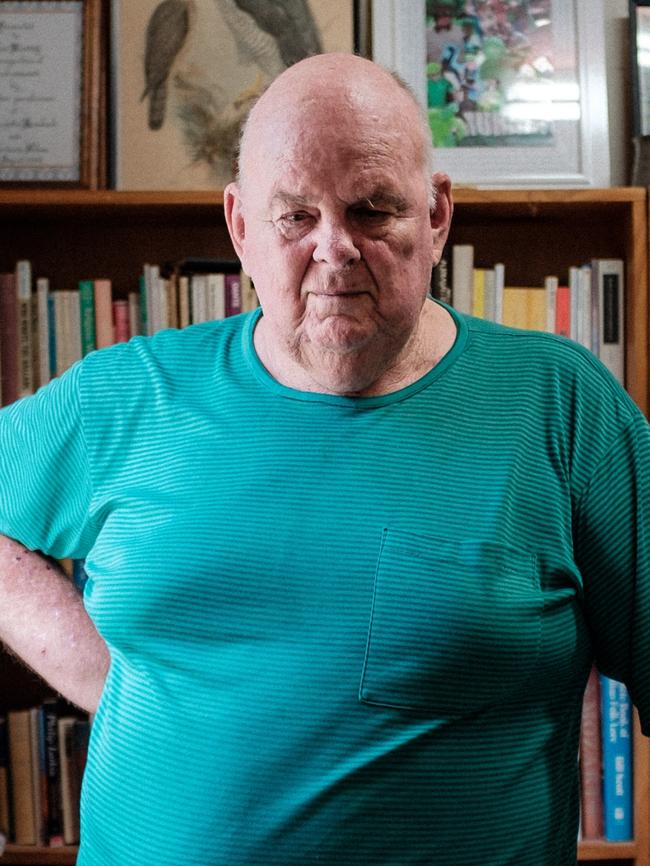

Why eminent poets Les Murray and John Tranter were at loggerheads.

Observant members of the Australian literary world have been amazed by the Times Literary Supplement of September 10, 2010. I read it and remembered our “Poetry Wars” of the 1960s and later, especially the skirmishes between Les Murray and John Tranter.

My shock was because that edition of the magazine published poems by those antagonists (Murray’s “The Blame” and Tranter’s “Gypsies”, each characteristic of its writer).

I suspect they had never previously appeared in the same publication, let alone in the identical edition.

What were those legendary “wars” and what were they about?

They were certainly fierce, personal and enduring. Ironically, those men had a great deal in common. Each had a background in rural NSW: Tranter was born in alpine Cooma (where, in his mother’s words, “a hot wind blew all summer long, full of dust; in the winter a bitter cold wind, and sometimes snow”); he grew up on the state’s southern-most coast.

Murray was located rather more northerly, one of an extended family of impoverished dairy farmers, in Bunyah.

They were about the same age and had, therefore, to contend with each other for name and fame; both were early dropouts from the University of Sydney’s English studies, though they were enviably gifted (how often are universities blind to those who are truly special?).

Murray became the peerless “Bard of the Bush” and always yearned to live where he found his congenial subject matter (his concern, he said was to write for “ordinary Australians”). Written in Murray’s preferred “homespun” style, “The Blame” has a rhyming scheme (even though irregular) and tells a rural story; Tranter was ever the modernist city poet and gladly lived there: “Gypsies” deals with the sybaritic patrons of a nightclub and is free in style, almost stream-of-consciousness.

Murray, of course, could also write about city life, and wittily: I mention two examples of many. In “Sidere mens eadem mutato”, the cycle of sonnets about his undergraduate days dedicated to his friend Bob Ellis, he mentions “Old Duncan who got the First Fleet away in August that year”. This was a reference to lecturer Dr MacCallum, who taught the early convict story of Australia and insisted on detailing its British pre-history: once, infamously, he ran out of time, having to conclude the course before the Fleet had even sailed from Portsmouth. Another was the marvellous image in “An absolutely ordinary rainbow” – “men with bread in their pockets leave the Greek Club” – which was literally true.

Each validates my theory that poets write for a small, knowing readership (their friends, really) who, through shared experiences, know and instantly understand those references which need no elaboration. Experience explained is experience diluted.

Tranter and Murray began writing at a time when battles were still common within our visual and literary worlds (the “Jindyworobaks”, a movement of writers strongest in the 1930s and 1940s, who wanted to integrate Indigenous cultural references into their works, being an example) about the location and home of the “real” Australian soul. Was it rural or urban? The archetype of that contestation was the “Ern Malley” hoax of 1943, which set the conservative poets, Harold Stewart and James McCauley, against Max Harris and John Reed (and their Angry Penguins magazine).

In an interview in 1991, Tranter reflected on his poetic influences. He had begun writing poetry when about 17: “I guess most people start writing poetry in adolescence; it has as much to do with hormones then as anything.”

Those influences were French and American, particularly “the poetry coming out of the US in the ’50s and ’60s (which) seems to me a time of extraordinary energy in English writing, like the Elizabethan age, or the Romantic period”.

Most would, surely, have been anathema to the laconic Murray, who (after a harsh and anti-intellectual childhood) also came to poetry in his late teens and, having read some Gerard Manley Hopkins, discovered that “poetry was about essences and about presence”. He immediately began writing, eventually choosing poetry and becoming a full-time poet in 1971.

Murray’s literary and personal animus towards Tranter endured fiercely, as his behaviour demonstrated in 1988. Peter Alexander (a South African biographer) and his wife, Christine were then in the school of English at UNSW, fresh from Oxford. They were persuaded by Gerard Windsor (writer in residence there) to organise a weekend “Creative Writers and Academics” conference. It was an apt theme because they well knew Murray’s animadversions against academics whom he misguidedly considered freeloaders, parasites of the work of creative writers who were poorly paid providers of the materials upon which academic work is predicated.

To him, the overpaid teachers operated merely at an unworthy remove and he resented that glaring discrepancy.

Nevertheless, he agreed to speak and was scheduled to do so on the Saturday afternoon. But he failed to keep his commitment. Subsequently, he did himself no honour by his assertion, in his book “Blocks and Tackles” (1990), that this withdrawal was on account of the depression that had dogged him for most of his life: “the Suspect Captivity of the Fisher King was sent to represent me at a conference I was too ill to attend” but “was not allowed to deliver because I was not there in person to present it!”.

A visibly shaken Alexander told me a quite different story during the lunch break: despite receiving the program several days in advance, the poet had just realised that Tranter would be speaking the following morning. Point blank, Murray refused to be a part of the same event. “You don’t have to be there for his paper,” Alexander protested. Murray insisted that he would never share the same room with Tranter, even if they were not actually together; it would be a form of personal defilement, but he suggested Alexander could read the paper instead.

With the details and animus deleted, the situation was explained to the audience. Realising the paper from Murray would be contentious and the following debate would be just as important, they resolved that the paper not be read. As subsequently published it was a philippic, which displayed all of Murray’s disdain for modernist poetry and poets.

Little wonder that he squibbed delivering it.

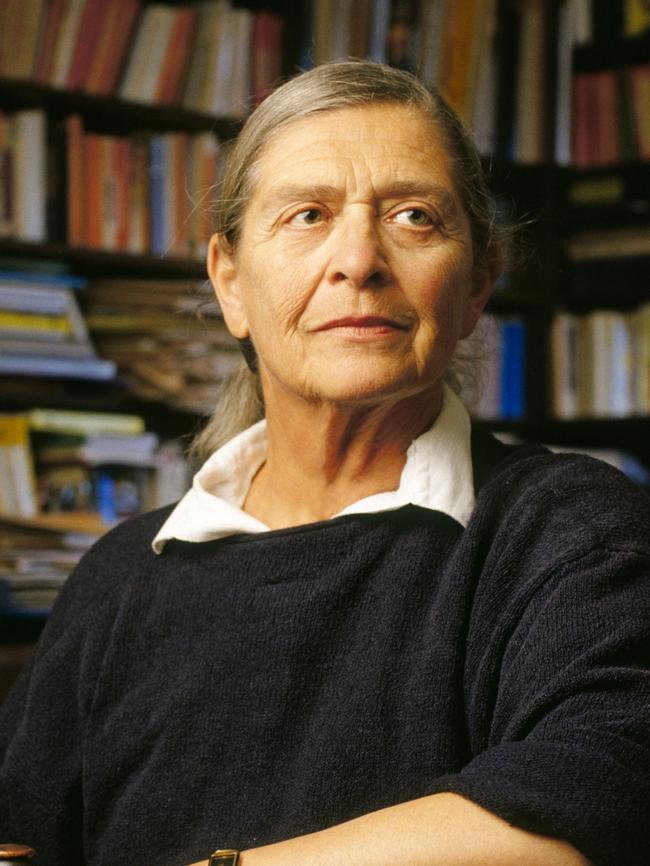

Some believe Murray was particularly angry because Fay Zwicky, both an academic and an eminent poet, had also been invited to speak.

Murray called her a “harpy” – one of Ovid’s ugly “human vultures”.

After hers, an address from Tranter (even if delivered next day, in Murray’s absence) would have been a bitter pill for Murray. Ironically, he would have agreed with part of her argument that a poet’s work on her or his craft is without end.

Alexander appeared to have learned little from that experience because, after the biography was completed, he decided a further book, of Murray’s letters, would be worthwhile. Murray agreed and contacted most of his correspondents urging them to comply. Alexander then spent years annotating the material but, with about 95 per cent of that work done, Murray, abruptly and callously, revoked his permission, which killed the project. The only reason he gave was the enduring hostility: Alexander would earn a pot of money from the book while he, Murray, would earn none.

After seeing that edition of the TLS in 2010, I wrote to Tranter and Murray about their battle; each replied with a brief postcard. Implausibly, Tranter denied all recollection but Murray’s response was extraordinary: after mentioning that he had no wish “to be set upon” at that UNSW conference, he returned to my original question: “If John Tranter played any intentional part in that horror, I forgive him.” What rewriting of history and obliteration of his own cruelty.

Very few people, even prolific writers, completely reveal themselves; do they really understand themselves? The saga gives a fresh meaning to the contemporary phrase, “culture wars”.

Of course, it is easier to admire their aesthetic output when one agrees philosophically with artists and their values. But the quiddity of the finest criticism is to separate partiality from admiration. That is not an easy task, but it can be done – by readers, listeners and viewers – if, infrequently, by great creators.

John Carmody is a former medical scientist who has written extensively on music, books and history.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout