John Tranter’s ‘Heart Starter’ takes cues from others’ verses

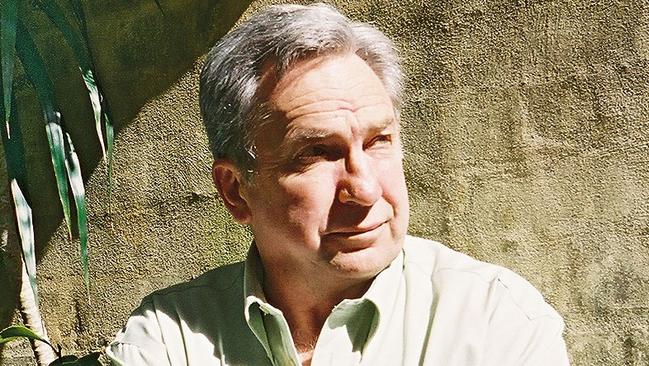

Nothing is quite at face value in the poetry of John Tranter, be it beautiful or ugly, charismatic or bland.

I remember on a sunny day in Perth back in March 2011 sitting under a tree on the University of Western Australia campus waiting for John Tranter to read from his just released and already lauded collection, Starlight — 150 Poems. It had been a pleasant enough afternoon, Peter Rose was chairing the readings, Kate Lilley and Mark Tredinnick were also appearing and, as is inevitably the case with such events these days, too great a percentage of the audience were poets themselves.

When Tranter came to the microphone I took an especial interest, having until then only ever encountered his prodigious body of work on the page. As soon as he began to read I understood something that a thousand pages of his work could never teach me. Here was a quiet but incisive voice, so finely honed that it seemed to have smuggled itself into the epicentre of the mining boom. His reading was phlegmatic, not studded with pompous allusions but full nevertheless of a wry erudition.

What struck me most, though, was how funny Tranter was. Standing in the sun like some public servant escaped for the lunch hour, he delivered his lines in a deadpan both sardonic and redemptively generous in tone.

Tranter’s poems often begin with the borrowed vacuity of ordinary spoken lines. In his new collection Heart Starter these include: ‘‘Thanks, I’m feeling a lot better’’, ‘‘God I was bored!’’, ‘‘Just look, will you, at those buildings’’, ‘‘Thanks: gin martini, straight up, no ice’’, ‘‘I’m sorry, I don’t think we’ve met’’, ‘‘Well, why don’t you ask him’’. With the canons of verse littered with indelible first lines — ‘‘Drink to me only with thine eyes’’, ‘‘I wandered lonely as a cloud’’, ‘‘Do not go gentle into that good night’’ — Tranter’s first lines are pointedly defunct. But as I discovered at that reading in Perth, they are also meticulously layered, full of lively energy and a naturally fool-ish air.

When casually idiomatic opening lines such as Tranter’s first began to appear in the work of 20th-century poets their very ordinariness was a call for liberation. Poets such as Frank O’Hara and Allen Ginsberg were revolutionary in their time but in Tranter’s distinctively Australian case such first lines are revolutionary in the literal, rather than the ideological, sense of the word. Things go around and return: voices, other people’s phrases, cinematic cliches, demotic postures, artistic methods and poetic modes.

Fittingly, then, Tranter does his eavesdropping not just at the bus stop or the cafe but as an active reader on the internet and the page. He is one of the most committed exponents of what the American critic Jed Rasula calls ‘‘wreading’’, that two-way engagement wherein reading and writing become the one act. In fact, despite the basic biographical detail that he was born in the NSW southern highlands town of Cooma in 1943, Tranter’s true sense of place and climate lies in the far more malleable and porous geography of poetic texts.

In Heart Starter Tranter’s method is to start with the end-words of the lines of another person’s poem and from that construct a new poem of his own. His predominant foundries here are two anthologies, The Best of the Best American Poetry 2013 and The Open Door: One Hundred Poems, One Hundred Years of Poetry Magazine, published in 2012. He calls the resulting poems ‘‘Terminals’’ and the persistent ambiguity the method provides him with is built from contradictory forces: on the one hand spontaneity, on the other a studied pose.

Like most of his work, Tranter’s Terminals have strong American highlights but the deeper seeds of these ironic wreadings lie further back in fin-de-siecle Paris, with the sceptical clarity of Baudelaire and also with Oscar Wilde’s deadly comment that ‘‘all bad poetry springs from genuine feeling’’. It would be true to say that just as Daniel Cohn-Bendit and the Parisian students of 1968 were detested by Left and Right alike, so too does Tranter exist, with a grin, in the space between.

I mention Paris 1968 because it is the generation from which Tranter comes, though in his case not with a megaphone but a palimpsest. As early as 1963, at the age of 20, he was firing up the Terminals method in a poem called Australia Revisited, in which he rearranged rhyme schemes and end-lines of AD Hope’s famous poetic manifesto, Australia. As it happens, Hope was also born in Cooma — and Tranter has since admitted to a degree of juvenile laureate-envy in writing that early poem. Naturally, though, the material he is composing in Heart Starter is less overbearing and the results are far more successful.

The poem Doting on Blubber for instance, whose first line is ‘‘Aren’t they beautiful, those jellyfish’’, is seeded by the poem Difference byAmerican poet Mark Doty. In Tranter’s hands the mild sugar of Doty’s North American sincerity is inflated into a comic paean to uncharismatic fauna and the absurdity of all odes. Each line-end corresponds with Doty’s but Tranter excels at ribbing and revving up the material.

For a start he positions himself not at Doty’s sympathetic distance from the subject but as kin to the unregarded formless blob behind the aquarium glass. This self-effacement, as always with Tranter, involves much cerebral jousting. For just like the jellyfish itself, Doting on Blubber has a rather intricate internal structure compared with which its appearance is misleading. In other words, reader beware. Nothing is quite at face value in Tranter, be it beautiful or ugly, charismatic or bland. The poem is a good example of the kind of allegorical stand-up he delights in, where the value of his technique lies in its ability to be accessible and intellectually complex at the same time.

If there is a downside to Tranter’s generative method it may be that it sets up a framework whereby any disjuncture can look cogent and therefore even some straight-out bad rhymes can be conceptually justified as part of the iconoclastic fun. This criticism connects in a general sense to the pitfalls of relativism in all postmodern art. An example in Heart Starter is Et in California Ego, triggered by Alice Stalling’s On Visiting a Borrowed Country House in Arcadia. Here Tranter’s adherence not only to Stalling’s aabbccdda verse pattern but also to ending each of his lines with the same word she does, leads to rhymes such as: ‘‘Yes honey you turn to look back but instead / the future appears before you, every day / longer than the last, your dog … say, / was that your dog Hobo disappearing behind that row’’.

The ‘‘day-say’’ constraint Tranter takes on via Stalling’s poem ends up lame in a way that even his ironic gifts can’t save. This is the risk of an addiction to games of formal constraint. At times the effect can come across as facile, the product of a nerdish cruciverbalist rather than a poet, when in fact the constant interplay between the subject and form of a poem needs always to be more than a game. For even if we accept Wilde’s maxim, an ontological acuity has to exist for a poem to rise above its numbers, as well as craft by ear. Otherwise it can languish in an obsessive cul de sac, which in Tranter’s case would seem contradictory to the openness and flexibility of his voice.

In the last section of Heart Starter Tranter forgoes the Terminal method in favour of one of his great loves, the sonnet. His interest in this form has been a constant in his work. Long before that afternoon in Perth, I remember reading his Crying in Early Infancy — 100 Sonnets, and being at once seduced and confronted by the ease with which he employed and rejigged the form’s romantic lineage. The examples in Heart Starter, 10 of which appeared in a 2013 chapbook published by Vagabond Press, continue that process. Here Tranter uses the five vowels of English — A E I O U — as synaesthetic nodes within the lines, which seems as much a play on the bullet list as it is a nod to Mallarme. Whatever the case the blend of linguistic abstraction with lyrical imagery is striking. One gets a sense in poems such as Tasman Sonnet, Mouton Cadet and Far North Farm of the language being spring-cleaned by experimentalism rather than merely toyed with. What is also abundantly clear is that Tranter’s inventive energy remains undiminished even into his 70s.

Gregory Day’s most recent novel is Archipelago of Souls.

Heart Starter

By John Tranter

Puncher & Wattmann, 149pp, $25

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout