Ern Malley hoax fit for poetic canon

Ern Malley has had a greater effect on Australia’s literary and artistic culture than any other poet.

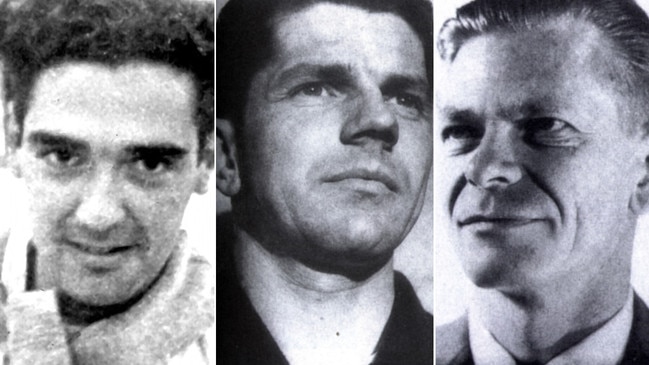

Ern Malley, who is alive and well, turns 100 today. The greatest literary hoax of the 20th century was perpetrated in 1944 by two relatively unknown poets, James McAuley and Harold Stewart, while they were serving in the Army Directorate of Research and Civil Affairs in Melbourne’s St Kilda Road Barracks. The target, Max Harris, was a precocious young Adelaide poet who was advocating cultural revolution through his avant-garde journal Angry Penguins.

With the help of a Collected Works of William Shakespeare, a rhyming dictionary and a report on mosquito breeding grounds, the pair knocked out a slim oeuvre of 17 poems in a single afternoon and evening. Or so they claimed. The poems were designed to be incoherent nonsense of the sort that would appeal to Harris and his clique but would easily be seen for what it was by readers of taste once the hoax was revealed.

The sparse details of Malley’s life were set down by the poet’s fictional sister, Ethel, in correspondence with Harris. After leaving high school at 14, Ern worked as a mechanic and an insurance salesman, spending most of his brief adult life in Melbourne before returning to Sydney to be nursed through the final stages of Graves’ disease (a non-fatal illness, if anyone had bothered to check). Ethel had found the poems while she sorted through Ern’s meagre possessions.

Such was Harris’s enthusiasm that he published the work before completing his inquiries. The poems appeared in a special edition of Angry Penguins with artwork by Sidney Nolan.

When the story broke in the Sunday Sun, the hoaxers revealed that the poems were “deliberately concocted, without intention of poetic meaning or merit, as an experiment to debunk what was regarded as a pretentious kind of modern verse-writing”.

Despite their disingenuous claims that Harris was not their target, he was undoubtedly the hoax’s primary victim.

Ern Malley has had a greater effect on Australia’s literary and artistic culture than any other poet. Beyond his stylistic influence on poets, he has inspired hundreds of poems, a play, an opera, numerous compositions — including one by Peter Sculthorpe — and a novel by Peter Carey. Probably Malley’s greatest contribution has been to the visual arts, from the Garry Shead paintings, included with ETT Imprint’s 2017 edition of the poems, to Nolan’s Ned Kelly paintings, which the artist thought impossible without the revelation of Ern Malley.

But are the poems simply cultural or historical artefacts? Are they any good?

It is interesting to read the poems through the eyes of the hoaxers, who thought their badness manifest. They were confident the poems’ schizophrenic shifts in tone, pretentious obscurities, arbitrary line endings and a vocabulary so jarringly multisyllabic would signal their mediocrity to any informed reader. So, too, the hyperbolic melodrama of lines such as: “On the mausoleum of my incestuous / And self-fructifying death”, or the banality of: “Princess, you lived in Princess St.”

More double-edged was the hoaxers’ deployment of literary allusion, designed to buttress Malley’s claims to erudition while undermining the credibility of the work. Shakespeare’s Pericles informs two of the poems, and Petit Testament is saturated in the language of Othello. These and other poems include numerous references to the Bible, Keats, Mallarme and Ezra Pound. But TS Eliot haunts the poems more than any other writer, and where Malley fails he can often sound like a bad quarto of The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock. Boult to Marina begins: “Only a part of me shall triumph in this / (I am not Pericles)”, which reads like a bare paraphrase of Eliot’s “No! I am not Prince Hamlet nor was meant to be,” and Eliot’s “set down this” becomes, through an addition as funny as it is pointless: “set down this too”.

Such allusions prove distracting rather than illuminating. Take the bathos of: “Reserving to myself a man’s / Inalienable right to be sad / At his own funeral”. Few can hear these lines without thinking of the US Declaration of Independence, but such a thought is undercut by the word “sad”, which sounds, well, pathetic.

Despite such deficiencies, it doesn’t take much to imagine Harris’s excitement on first opening that envelope. Energy is, perhaps, the most important quality of lyric poetry, and the energy of Malley’s work is palpable. The poems were utterly unlike anything Australia had hitherto produced — and reading them, 74 years on, is still an ecstatic rush. But different lines will appeal today. My favourite passage reads: “And in conclusion: / There is a moment when the pelvis / Explodes like a grenade”. These lines are comic largely because “in conclusion” gives them the flavour of a high school essay, but they could hardly appeal to a modernist reader schooled in the learned irony of Eliot.

Following the tentative inclusions of a few poems during the 1970s and 80s, John Tranter and Philip Mead published Malley’s entire oeuvre in The Penguin Book of Modern Australian Poetry (1991). Since then Malley has become a fixed feature of most anthologies of Australian literature, and his presence in the sixth edition of The Norton Anthology of Poetry (2018) suggests canonical status. Some of the poems the hoaxers claimed the silliest, such as Petit Testament, have proved favourites for anthologists.

Had Harris not published the poems, they would remain in obscurity. The consistent irony accompanying their publication is that anthologists generally claim their choices are independent of the hoaxers’ intentions, while the value of the poetry is still underwritten by the myth that Harris found so appealing — perhaps more appealing still to contemporary readers.

Last year, South Australia’s History Festival included an Ern Malley event that was better attended than any poetry reading I’ve been to. Peter Goldsworthy, who quipped that Malley would have been a better poet had he lived longer, reminded the audience of the youthfulness of the hoax’s central players: Stewart was 27, McCauley 26 and Harris only 22 at the time. Who among us stands by judgments made at that age? But Harris kept insisting on the quality of the poems.

History suggests he got it right.

Aidan Coleman is an Adelaide poet and critic.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout