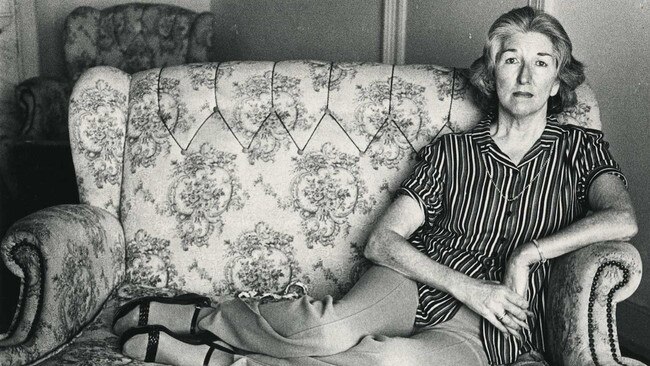

Australian author Elizabeth Harrower dead, aged 92

Once compared to Fyodor Dostoevsky, Elizabeth Harrower, one of Australia’s most important writers, has died.

“I don’t know anybody who knows I’m a writer.” That was Elizabeth Harrower’s no-nonsense assessment of her literary career in 2012. She was soon to be proven wrong.

In the near-decade that followed that verdict, Harrower, who died on Tuesday July 7, aged 92, became one of Australia’s most important writers, here and overseas. And she did so without writing another word.

Indeed, Harrower stopped writing in the mid-70s, not long after the death of her mother.

Her four novels, Down in the City, The Long Prospect, The Catherine Wheel and The Watch Tower, published between 1957 and 1966, were “dead and buried”, to quote publisher Michael Heyward. “She was the writer we never knew,’’ Heyward says.

It was Heyward, and his wife Penny Hueston, who run Melbourne-based Text Publishing, who decided to resurrect Harrower’s career. They reprinted, via the Text Classics imprint, her novels and even convinced her, after a lot of persuading, to publish the novel she abandoned in 1971, In Certain Circles.

The critical and public response went beyond anyone’s dreams, particularly Harrower’s. The English critic James Wood, one of the world’s most influential literary voices, devoted thousands of words to the author and her books in The New Yorker in October 2014.

Wood compared Harrower to Fyodor Dostoevsky and singled out her “wounded wisdom, the elegance and strictness and perilous poise of her sentences, the humane understanding, and ceaseless incisions, of her intelligence’’.

Harrower, who lived in Sydney, embraced her “new” readers, travelling to book talks and literary festivals around Australia. In one memorable moment she travelled by car, piloted by her friend Jane Novak, who is a literary agent, to the 2017 Adelaide Writers Week, which was dedicated to her.

“She became a sort of rock star,’’ says Heyward.” “It was wonderful for Elizabeth in the last 10 years of her life to know her books were being read.”

When Harrower arrived at the Adelaide event, there were more than 1500 people in the audience, massed to see, as then festival director Laura Kroetsch put it, “one of the greatest writers of the 20th-century’’.

Harrower was born in Sydney on February 8, 1928. She spent most of her childhood in Newcastle, living with her grandparents, following her parents’ divorce.

She moved to London in her early 20s. It was in London that she wrote her first three novels, Down in the City (1957) and The Long Prospect (1958) and The Catherine Wheel (1060).

She returned to Sydney in 1959 and worked on The Watch Tower and then the novel, In Certain Circles, that she decided not to publish, until Heyward came along 40 years later. Harrower had been in poor health for the past two years. She died in a care home in Sydney. She never married and had no children.

Harrower’s novels were urban, not rural. They considered domestic violence, especially of the psychological kind. “Emotional tyrants” is a good description of some of her male characters.

“I‘ll never forget reading Elizabeth for the first time,’’ says dual Miles Franklin winner Michelle de Kretser.

“The Watch Tower dissected an abusive marriage with such disturbing, forensic accuracy that at times I could barely read on. Intimate cruelty was Elizabeth’s great subject and she picked it over with unflinching brilliance.

“A great tree has fallen in my patch of the forest now that she’s gone.’’

Geordie Williamson, The Australian’s chief literary critic, says that “like Patrick White, Harrower was a visionary who worked at ground level, a writer who sought and found sublimity in a broken creation’’.

“I feared her piercing gaze as a person. I adored her unassailable honesty as a writer. She was a feminist before our culture would allow her to be. But she was a truth-teller, always, consequences be damned.’’

Harrower came from the time that produced two of Australia’s greatest writers, White (born 1912) and Christina Stead (born 1902). She knew them both and was also friends with the artist Sidney Nolan and his writer wife Cynthia.

That quote from 2012, in an interview with Gay Alcorn, about nobody knowing she is a writer goes further. “The people who did understand are dead. Patrick. Cynthia. Richard.’’ Richard was writer and political adviser Richard Hall.

“Yes, she belonged to the era of Patrick White and Christina Stead and as a writer she belongs in their company,’’ Heyward says.

The older writers agreed at the time. Writing about The Long Prospect, Stead said Harrower “has no equal in our writing”. White, Australia’s only Nobel laureate in literature, once inscribed a book for Harrower: “To Elizabeth, luncher and diner extraordinaire. Sad you don’t also WRITE.”

“Patrick was always very angry with me for not writing,’’ Harrower told Alcorn. “He was horrible. Only people who really care about you care about whether you are doing that or not.’’

White was right about Harrower’s love of a good time. She liked lunches with friends, she liked books, movies music and art. Heyward fondly remembers her flirtatious behaviour during interviews with him. “She was a major writer,’’ he says, “and quite a character.’’